The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn (2 page)

Read The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn Online

Authors: Eric Ives

How one would have felt about her is another matter. Captivating to men, Anne was also sharp, assertive, subtle, calculating, vindictive, a power dresser and a power player, perhaps a figure to be more admired than liked. But against that is Anne’s greatest distinctiveness, something she shares with only one other English queen: she married for love. Her relationship with Henry was deeply personal in a way kings had risked only once before, and never did again until the twentieth century. The couple’s attempt to have an affectionate marriage, with perceptible hints of modernity in the context of a Tudor court, explains much of the life and death of Anne Boleyn. It also means that the more we understand Anne, the more we understand the greatest puzzle of the Tudor century, the personality of her husband Henry; as the saying goes, ‘it takes two to make a marriage.’

This book is structured in four parts. ‘Background and Beginnings’ deals with Anne’s origins, her education, her launch into English court life and the reasons for the impact she made. That leads on to a discussion of the romantic relationships which she had or is supposed to have had, and hence to her agreement to marry the king. ‘A Difficult Engagement’ looks at the oft-told history of Henry VIII’s attempt to free himself to marry, but with a focus on Anne which undermines male-dominated interpretations of tradition. Part III, ‘Anne the Queen’, examines Anne’s marriage and consequent lifestyle, offering a picture of what it meant to be the consort of an English king at a magnification well in excess of what is possible for almost all her predecessors. Illustrating this is a nearly complete display of such visual evidence as has survived, which, in turn, supports detailed discussions of Anne’s portraiture, of her role as an artistic patron, of the day-to-day context of royal living and of her mind and beliefs. The final section, ‘A Marriage Destroyed’, concentrates on the closing months of the queen’s life, demonstrating the sudden and unexpected nature of her fall, the coup which precipitated it, the dishonesty of the case against her and the tensions of her last days.

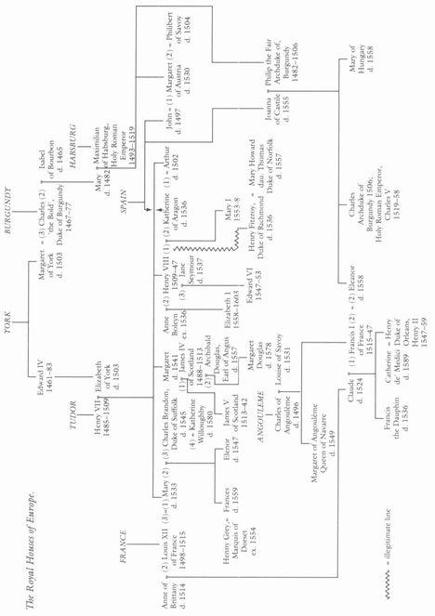

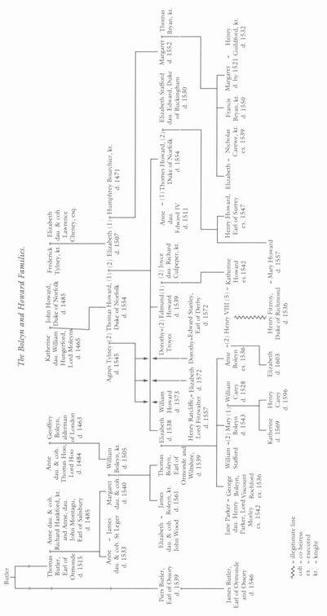

Tudor history (especially court history) is a minefield of possible confusion arising from family names, changing peerage titles and the fluctuations of office-holding. I have therefore provided a brief explanatory list. Relationships can be equally confusing, so family trees of the royal houses of Europe, the nobility of Henry VIII’s court, and the Boleyn and Howard families are also included. In the index individuals are cross-referenced to a main entry under the family name. A full bibliography of relevant material would be impossibly large, but a list of titles frequently cited and therefore abbreviated can be found before the index. Other works have been cited in full in the notes. Where the place of publication is not given, London must be understood. Spelling in quotations has been modernized.

No biographer of Anne Boleyn comes to the subject without debts. Particularly since the 450th anniversary of Anne’s execution in 1986, a significant number of monographs and papers have opened or reopened issues affecting every stage of her life. Many of these contributions are discussed in the body of the text or figure in the notes, and my particular debt to James Carley and Gordon Kipling will be obvious. Not everyone is persuaded by my picture of Anne, and I am especially grateful to George Bernard for jousts which have sharpened up my analysis. Two substantial studies within discussions of Henry VIII’s complete matrimonial record deserve special mention - Antonia Fraser’s

The Six Wives of Henry VIII

and, more recently, David Starkey’s

Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII.

I do not always agree with them, but scholarship would be poorer without work of such quality. Furthermore, it is to Starkey that we owe the publication of

The Inventory of King Henry VIII

, henceforth an absolutely vital text. I have also benefited much from regular communication with Bob Knecht, particularly the chance to bounce off issues in sixteenth-century England against the situation in France and vice versa.

The Six Wives of Henry VIII

and, more recently, David Starkey’s

Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII.

I do not always agree with them, but scholarship would be poorer without work of such quality. Furthermore, it is to Starkey that we owe the publication of

The Inventory of King Henry VIII

, henceforth an absolutely vital text. I have also benefited much from regular communication with Bob Knecht, particularly the chance to bounce off issues in sixteenth-century England against the situation in France and vice versa.

Many scholars and friends have helped me with particular points of difficulty, including Alan Douglas, Marguerite Eve, Joan Glanville, John Guy, Gary Hill, Richard Hoyle, Mme Nicole Lemaitre, Virginia Murphy, Geoffrey Parnell, Peter Ricketts and Barry Young. Over many years of studying the Tudor court and especially Anne Boleyn, I have also incurred considerable debts for the use of manuscripts and other material: to His Grace the Duke of Northumberland and to the archivist at Alnwick Castle, Dr Colin Shrimpton, for ready access to the Percy papers; to His Grace the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry for the use of the miniature of Anne Boleyn by John Hoskins; to Mr Robert Pullin for his generous help with the Hever Castle collection; to the Eyston family for access to its papers; to Patricia Collins at the Burrell Collection for introducing me to Anne’s needlework. Many librarians, curators and their staffs have willingly assisted and advised, especially Miss Janet Backhouse, lately of the British Library Department of Manuscripts; the staffs of Special Collections, the Barber Institute and the Shakespeare Institute, all of the University of Birmingham, notably Miss Christine Penney and two erstwhile colleagues, Dr Ben Benedikz and Dr Susan Brock; Dr Christiane Thomas of the Osterreichisches Staatsarchiv, Vienna, and Dr Christian Müller of the Kunstmuseum Basel.

Whatever merit this biography has is owed, in great measure, to the kindnesses of those named and others unnnamed. Its faults and longueurs are mine, and more than the dedicatee would have passed had she been here to subject the text to her eagle eye.

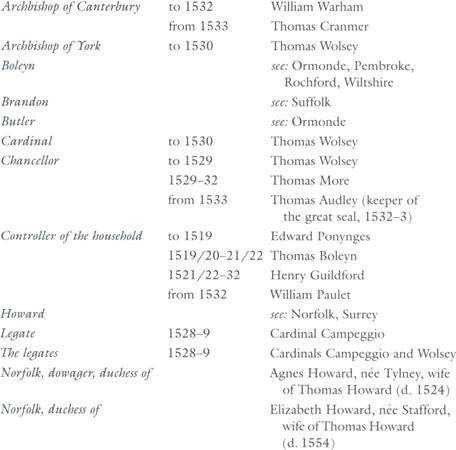

TITLES AND OFFICES

I

N the nearly forty years of Anne Boleyn’s story, it is inevitable that office-holders and ranks altered. The following list sets out the principal identifications; for further details, see the index and the family trees.

N the nearly forty years of Anne Boleyn’s story, it is inevitable that office-holders and ranks altered. The following list sets out the principal identifications; for further details, see the index and the family trees.

PART I

BACKGROUNDS AND BEGINNINGS

1

A COURTIER’S DAUGHTER

A

NNE Boleyn was born, so tradition goes, at the fairy-tale castle of Hever in the Weald of Kent. Reconstructed by the Astor family in the twentieth century, Hever remains a romantic shrine to Anne and her love affair with Henry VIII. Unfortunately for romance and tradition, Anne was in fact born in Norfolk, almost certainly at the Boleyn home at Blickling, fifteen miles north of Norwich. The church there still has brasses of the family. The Boleyns certainly owned Hever, although it was less a castle than a comfortable manor-house which her great-grandfather, Geoffrey, had built within an existing moat and curtain wall, and it did become the principal residence of her parents. But Matthew Parker, who became archbishop of Canterbury in 1559 and had earlier been one of Anne’s private chaplains, was quite specific that she came, as he did, from Norfolk.

1

NNE Boleyn was born, so tradition goes, at the fairy-tale castle of Hever in the Weald of Kent. Reconstructed by the Astor family in the twentieth century, Hever remains a romantic shrine to Anne and her love affair with Henry VIII. Unfortunately for romance and tradition, Anne was in fact born in Norfolk, almost certainly at the Boleyn home at Blickling, fifteen miles north of Norwich. The church there still has brasses of the family. The Boleyns certainly owned Hever, although it was less a castle than a comfortable manor-house which her great-grandfather, Geoffrey, had built within an existing moat and curtain wall, and it did become the principal residence of her parents. But Matthew Parker, who became archbishop of Canterbury in 1559 and had earlier been one of Anne’s private chaplains, was quite specific that she came, as he did, from Norfolk.

1

Tradition also tells us that the Boleyns were a family of London merchants, and again tradition leads us astray. Anne Boleyn was born a great lady. Her father, Thomas, was the eldest son of Sir William Boleyn of Blickling, and her mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of Thomas Howard, earl of Surrey, one of the premier noblemen in England. There was mercantile wealth in the family, but to get to that we have to go back to Geoffrey Boleyn, the builder of Hever. He had left Norfolk in the 1420s, made his fortune as a mercer in London, served as an alderman and become Lord Mayor in 1457 — 8. Fifteenth-century England, however, was a society open to wealth and talent. Had not William de la Pole, the most powerful man in England, been created duke of Suffolk in 1448, and his great-grandfather a merchant from Hull? It is no surprise, therefore, that Geoffrey Boleyn was able to secure as his second wife one of the daughters and joint heiresses of a nobleman, Thomas, Lord Hoo. William, the eldest surviving son of that marriage, made an equally good match with Margaret Butler, daughter and co-heiress of the wealthy Anglo-Irish earl of Ormonde, so that when their eldest son, Anne’s father, married a daughter of the earl of Surrey he was continuing a tradition into the third generation. As a result — and this should finally dispel all smell of the shop - Anne’s great-grandparents were (apart from Geoffrey) a duke, an earl, the granddaughter of an earl, the daughter of one baron, the daughter of another, and an esquire and his wife.

2

Anne Boleyn came, in fact, from the same sort of background as the majority of the Tudor upper class. Indeed, she was better born than Henry VIII’s three other English wives. Marrying Anne did not, as has been unkindly said of Jane Seymour, give the king ‘one brother-in-law who bore the name of Smith, and another whose grandfather was a blacksmith at Putney’.

3

2

Anne Boleyn came, in fact, from the same sort of background as the majority of the Tudor upper class. Indeed, she was better born than Henry VIII’s three other English wives. Marrying Anne did not, as has been unkindly said of Jane Seymour, give the king ‘one brother-in-law who bore the name of Smith, and another whose grandfather was a blacksmith at Putney’.

3

The Boleyns, thus, were not bourgeois, but Geoffrey’s wealth had enabled his son William to establish himself as a leading Norfolk gentleman. Knighted in 1483, he became a Justice of the Peace and one of that elite of country gentlemen on whom the Crown relied in time of crisis.

4

By contrast, the position of his son and heir remained decidedly equivocal so long as Sir William lived. Thomas was the prospective successor to great wealth - the Boleyn and Hoo estates, half of the Ormonde fortune and half of the lands of the wealthy Hankford family, inherited from his Butler grandmother — but in the meantime he had to exist on an annuity of fifty pounds a year, the occupancy of Hever, and whatever his own wife had brought him.

5

That was probably not much, for the earl of Surrey had only just completed the expensive task of buying back the Howard lands he had lost after his ill-judged support for Richard III at the battle of Bosworth. With the fifty pounds and his wife’s portion Thomas Boleyn was not penniless, but he had nowhere near the income to sustain his pretensions, or that high profile which was necessary if he was to achieve his full promise — even, perhaps, the revival of the Ormonde earldom in his favour. The Howard marriage and the influence of his Butler grandfather did, nevertheless, offer one immediate prospect: an entry to the traditional career of the ambitious English gentleman, royal service.

6

In 1501 Boleyn graced the marriage of Katherine of Aragon to the king’s eldest son, Arthur, and in 1503 helped to escort the king’s eldest daughter, Margaret, to her marriage with the king of Scotland.

7

By the time Henry VII died, in the spring of 1509, Anne Boleyn’s father had risen at court to the important rank of ‘squire of the body’, and as he walked in the king’s funeral procession, clad in his newly issued black livery, he could reflect that since his father had died in 1505 and the old earl of Ormonde was about 85, his private fortune now looked good also.

8

4

By contrast, the position of his son and heir remained decidedly equivocal so long as Sir William lived. Thomas was the prospective successor to great wealth - the Boleyn and Hoo estates, half of the Ormonde fortune and half of the lands of the wealthy Hankford family, inherited from his Butler grandmother — but in the meantime he had to exist on an annuity of fifty pounds a year, the occupancy of Hever, and whatever his own wife had brought him.

5

That was probably not much, for the earl of Surrey had only just completed the expensive task of buying back the Howard lands he had lost after his ill-judged support for Richard III at the battle of Bosworth. With the fifty pounds and his wife’s portion Thomas Boleyn was not penniless, but he had nowhere near the income to sustain his pretensions, or that high profile which was necessary if he was to achieve his full promise — even, perhaps, the revival of the Ormonde earldom in his favour. The Howard marriage and the influence of his Butler grandfather did, nevertheless, offer one immediate prospect: an entry to the traditional career of the ambitious English gentleman, royal service.

6

In 1501 Boleyn graced the marriage of Katherine of Aragon to the king’s eldest son, Arthur, and in 1503 helped to escort the king’s eldest daughter, Margaret, to her marriage with the king of Scotland.

7

By the time Henry VII died, in the spring of 1509, Anne Boleyn’s father had risen at court to the important rank of ‘squire of the body’, and as he walked in the king’s funeral procession, clad in his newly issued black livery, he could reflect that since his father had died in 1505 and the old earl of Ormonde was about 85, his private fortune now looked good also.

8

Other books

Escape from Wolfhaven Castle by Kate Forsyth

Homefront by Kristen Tsetsi

The Steps by Rachel Cohn

Babycakes by Armistead Maupin

Magic by Danielle Steel

Boomers: The Cold-War Generation Grows Up by Victor D. Brooks

Devious Minds by KF Germaine

Becoming His Slave by Talon P. S., Ayla Stephan

Death of Yesterday by M. C. Beaton

Hidden Riches by Felicia Mason