The life of Queen Henrietta Maria (5 page)

Read The life of Queen Henrietta Maria Online

Authors: Ida A. (Ida Ashworth) Taylor

Tags: #Henrietta Maria, Queen, consort of Charles I, King of England, 1609-1669

It is true that, remembering the issue of the Spanish negotiations, protracted over years only to end in total failure, the alleged desire of the French authorities to accelerate those now to be set on foot is not without excuse. The mission of Lord Kensington, afterwards Earl of Holland, marks the next stage in the progress of events.

The agent selected for the purpose of sounding the French Government before a formal proposal of marriage should be hazarded was admirably adapted for the task. Coupled by Sir John Eliot with the Duke of

Buckingham, his patron and friend, both are described by the national leader as "young and gamesome, fitter for sports than for business." Yet Kensington showed himself adroit and skilful in the matter of the marriage negotiations. He was also eminently successful in turning to account the opportunity afforded him of securing for himself the favour of the future Queen. In the years that were to follow, and until it had been proved beyond doubt that he was undeserving of her confidence, Henrietta remained faithful to the friendship inaugurated at the time of his embassy ; and the part played by the envoy in her future life was an important one.

By Clarendon's account, as accomplished a courtier as any to be found in the palaces of all the princes of Europe, Kensington was also versed in affairs of State, domestic and foreign ; and—what was scarcely of less consequence in his present employment—was " of a lovely and winning presence, and gentle conversation." Wise in his generation, he had not only sedulously cultivated the goodwill of the all-powerful favourite, but had refrained from any endeavour to establish a personal relationship between himself and James. The success of this line of conduct was apparent in the fact that " the King scarce made more haste to advance the Duke than the Duke did to promote the other." He is, indeed, said to have been the only man at court, not of Buckingham's own kin, whom the favourite loved and trusted. The Duke's confidence was now shown by his appointment to fill the post of ambassador extraordinary, in all but the name, to the court of France.

In February, 1624, the envoy reached Paris. On the day following his arrival he sent an account of his reception to the Duke, his patron.

LORD KENSINGTON IN PARIS 33

It had been on a Sunday evening that he had found himself at his destination ; and hearing that the young King was expected to leave Paris the next day he determined to lose no time in presenting himself at court, that he might kiss Louis' hands [before his departure and assist at the Queen's masque, arranged to take place that night. To the palace he therefore repaired on the evening of his arrival.

In the chamber of the Due and Duchesse de Chevreuse, to whom he seems first to have gone to pay his respects, he found husband and wife engaged in dressing for the performance. An hour later the Queen herself, with Madame Henriette, joined the party and stayed " a great while." And it was observed, adds Kensington, " that Madam hath seldom put on a more cheerful countenance than that night." He might guess, he was told, at the cause. On the envoy Madame made a most favourable impression. She was, according to his account, lovely and sweet. Her growth, it was true, was not great, but her shape was perfect, and every one swore her sister, now tall and goodly, had been no taller at her age.

No business could be done that night, especially as Kensington was at some pains to disown any more important errand than one of mere goodwill. In his next letter to the Duke, however, he is able to report progress. The Queen-Mother, whom he finds to be the chief power at Court, is favourable to the English interests, and had given him explicitly to understand that she had not lost her inclination for the proposed marriage : " More than this she could not, she thought, well say, it being most natural for the woman to be demanded and sought."

To the Prince himself, in a letter of February 26th, VOL. i. 3

the envoy gave additional details as to his proposed bride.

" Sir, if your intentions proceed this way, as by many reasons of State and wisdom (there is cause now rather to press than slacken it), you will find a lady of as much loveliness and sweetness to deserve your affection as any creature under Heaven can do. And, Sir, by all her fashions since my being here, and by what I hear from the ladies, it is most visible to me, her infinite value and respect unto you. ... I must somewhat more say of admiration for the person of Madam, for the impressions I had of her were but ordinary ; but the amazement extraordinary to find her, as I protest before God I did, the sweetest creature in France. Her growth is very little short of her age, and her wisdom infinitely beyond it. I heard her discourse with her mother and the ladies about her with extraordinary discretion and quickness. She dances (the which I am a witness of) as well as ever I saw any creature. They say she sings most sweetly ; I am sure she looks so."

In the meantime Kensington himself, partly no doubt in his character of envoy, but also owing to personal attraction, was winning golden opinions at the French court. Though addressing himself in the first place, according to his instructions, to Maria de Medicis, he had evidently succeeded in ingratiating himself through Madame de Chevreuse with her mistress, the young Queen ; and so well had he excited the imaginations of both with regard to the Duke of Buckingham in particular, that he was able to announce that a reception beyond the usual terms of courtesy was awaiting his patron whenever it should please him to visit France. His letters home continued, on the other hand, to be well calculated to take effect upon Charles' romantic

disposition, and to increase his desire that the fresh marriage project should be brought to a successful conclusion.

A quasi-message from the young Queen contains a curious congratulation upon his escape from Spain and from the negotiations which had had for their object a match with her own sister. " She says," Lord Kensington reported, " she durst say you were weary with being [in Spain], and so should she, though she be a Spaniard." It was again clear that Anne of Austria had, in biblical phrase, forgotten her own country and her father's house, and was ready to throw herself into the interests of her husband's family. She made Kensington display the Prince's portrait, showed it to her ladies with infinite commendation, and added her hopes that some good occasion might bring Charles to Paris, so that they might see him "like himself."

Henrietta, not unnaturally, felt it hard that she alone should be debarred from the contemplation of the Prince's portrait—" she whose heart was nearer it than any of the others." Accordingly, she contrived that it should be secretly borrowed from the owner and brought to her, when, retiring to her cabinet with a single witness, she opened it in haste and blushing, kept it for an hour, and made herself well acquainted with the features of the man to whom circumstances pointed as her future husband. " Sir," adds Kensington, after relating the incident, " this is a business so fit for your secrecy as I know it shall never go further than to the King your father, my Lord Duke of Buckingham, and my Lord of Carlisle's knowledge. ... I would rather die a thousand times than it should be published, since I am by this young lady trusted, that is for beauty and goodness an angel."

So far all was going as well as could be wished. Kensington may fairly have congratulated himself upon the success of his diplomacy. The attempts made by the Spanish ambassador to interpose hindrances by "letting them know that the Prince cannot have two wives, for the Infanta is surely his," completely failed in their object ; and so favourably had the preliminary mission prospered that Kensington was before long joined in Paris by the Earl of Carlisle, his own close and intimate friend, both being formally invested with the character of ambassadors extraordinary, instructed to carry on the marriage negotiations.

Kensington's new colleague was a Scot, brought by James to England at the time of his accession. Bred in France, he had been regarded with more favour by the King's new subjects than any other of his unpopular nationality ; and his master's efforts had secured for him two wealthy wives—the first the heiress of Lord Denny, and the second the beautiful Lady Lucy Percy, daughter of the Earl of Northumberland, and afterwards Henrietta's own ill-chosen friend. " A very fine gentleman and a most accomplished courtier," Carlisle was noted for his habits of luxurious extravagance, and was no less well adapted than Kensington to produce a good impression at the Louvre.

The single discordant element at court was represented by Henrietta's disappointed lover, Soissons. As the hopes of those desirous of the English alliance rose higher, the patience of Madame's young cousin became exhausted. Irritated at the magnificent reception ao corded to Charles' delegates, the lad not only storme against the match, but manifested his indignation " mor fully than discreetly" by a refusal to acknowledge Kensington's salute. Taken to task for this exhibition

ic

;

•e

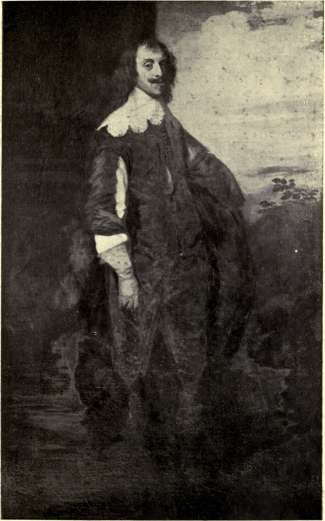

From the picture by Van Dyck, by permission of Viscount Cobham. JAMES HAY, EARL OF CARLISLE.

of temper, he replied that it was caused by no personal ill-will towards the envoy, but only to his errand, which went so near his heart that, had it not been on behalf of so great a prince, he would have cut Kensington's throat. After this outbreak the young Count seems to have quieted down and reconciled himself to the inevitable, since he is next found accepting the present of an English horse offered him by the ambassador. With this one exception unanimity prevailed as to the desire that the negotiations should be brought to a successful issue. But though Kensington, by whom the vicarious courtship appears still to have been chiefly carried on, was permitted greater frequency of access than before to Madame, and was allowed to entertain her " with a more free and amorous language" on behalf of his master, the state arrangements, dealing with practical difficulties rather than with sentiment, made slow progress. In a conversation with the Queen-Mother the envoy took her lightly to task for the treatment his Prince was receiving. In adverting to the miscarriage of the Spanish alliance, Marie de Medicis had observed—not, one imagines, without satisfaction—that Charles had been used ill in Spain.

Kensington admitted the fact.

" So he was," he allowed ; " but not in his entertainment . . . but in their frivolous delays and . . . unreasonable conditions. . . . And yet," he added, smiling, " you here, Madam, use him far worse."

" And how so ? " questioned the Queen.

" In pressing upon him the same, and even more unreasonable, conditions than Spain," answered the ambassador boldly. After which he demanded permission to entertain Madame with his master's commands.

Marie made difficulties. What, she questioned, would Kensington say to her ?

c< Nay, then, Madam," rejoined the envoy, again smiling ; " your Majesty would impose on me the like law that they did in Spain upon his Highness" —in refusing Charles freedom of intercourse with the Infanta.

The case, the Queen contended, was different. The Prince was not now present in person, but only by deputy.

" But a deputy representing his person," Kensington urged.

The Queen, one fancies, began to lose patience.

" Mais pour tout cela, qu'est-ce que vous direz ?" she insisted.

" Rien qui ne soit digne des oreilles d'une si vertueuse Princesse," returned Kensington loftily. Pressed again, he consented to furnish Henrietta's mother with an outline of the second-hand love-making he had prepared. Having been granted more liberty of language than before, he obeyed his Prince's command in presenting his service to Henrietta, not now out of mere compliment, but prompted by the passion and affection kindled in him by her outward and inward beauty. Such was to be the drift of his remarks, together with the expression of Charles' determination to do all he could in furtherance of the alliance.

Marie was pleased to approve.

" Allez, allez," she exclaimed graciously, " il n'y a pas de danger en tout cela. Je me fie de vous."

Proceeding to seek Henrietta herself, Kensington accordingly made his speech, " amplifying it a little more,' though not abusing the confidence placed in him by the Queen-Mother. Madame, for her part, courtesying low in acknowledgment, declared herself extremely obliged

to his Highness, and would think herself happy in an occasion of meriting her place in his good grace's affections.

This was all very well, and is no doubt an example of what was taking place day by day through the long months occupied by tedious controversy and diplomatic finesse. But the negotiations still halted. Fresh conditions were made by the French Government. The Pope disliked the match, and the religious difficulty threatened to prove insuperable. On August 24th, in an angry letter to Carlisle, Charles bade his envoy dally no more, and if necessary break off the marriage treaty, though preserving if possible friendly relations with the Government. A further effort was, indeed, to be made to bring matters to a successful conclusion, " for I respect the person of the lady as being a worthy creature, fit to be my wife ; but as you love me, put it to a quick issue."