The Lights of Pointe-Noire (11 page)

Read The Lights of Pointe-Noire Online

Authors: Alain Mabanckou

I smile at him as I take the notes from my pocket.

Close encounters of the third kind

T

here's a knock at the door, I open it, and find Uncle Matété standing there. He's come with a little bunch of bananas, which he puts down in the middle of the room. I pick it up and take it through to the kitchen, while he looks round my rooms, with undisguised amazement.

âDo the whites pay for you to stay in this place?'

I explain that the French Institute invited me to attend a conference for a few days, and I decided to extend my stay, to see the family, and write a book.

âAnd how much do you pay to stay here?' he replies, going out on to the balcony.

âThey make this apartment available for writers and artists, I don't pay anything.'

âI came yesterday, it's hard to get hold of you, I must have been back three times! This is all very nice, isn't it?'

Without waiting for my reply, he points over at the building opposite:

âLook, even at night you can see the Adolphe-Sicé hospital really clearly! Have you visited Bienvenüe there yet?'

âNoâ¦'

âI don't blame you. You're scared of Room One too, I guess? Anyone who goes in, even just to visit, will end up there one day to dieâ¦'

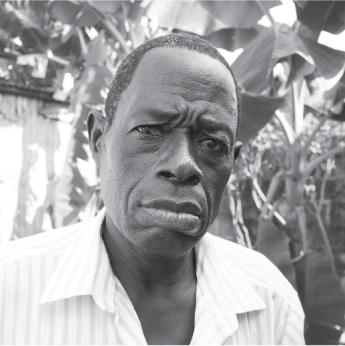

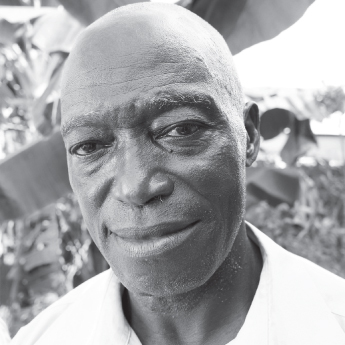

By night the hospital looks like a huge haunted manor house, with dim, uneven lighting issuing from the few windows still left open. Uncle Matété suddenly falls silent. He passes his hand over his close-cropped skull, which gleams with the light from the moon emerged from the dark clouds cast over the town. I imagine what he must thinking, how far his thoughts will take him. His eyebrows are quite grey and I sometimes think he looks older than Uncle Mompéro, who he gets on well with, and who was the one who told me he would be coming to see me, though I hadn't been sure it would be today, this evening. They are both the children of Grandfather Grégoire Moukila, by different mothers.

I guess Uncle Matété's thinking back to when I was a child in Louboulou village. I was around ten years old, and it was my first time in the bush. The second day of my visit, he decided to take me hunting with him, despite my mother's objections, and my grandmother N'Soko's indignation. Grandfather Moukila intervened to reassure everyone:

âLet them go, they'll be all right, my spirits will watch over them. After all, the boy needs to go there, before it's too lateâ¦'

I have never forgotten our nocturnal escapade. I arrived home on my uncle's shoulders, my legs scraped raw with scratches and grazes, my face covered in insect bites. Uncle Matété borrowed Grandfather's shotgun and we left at the dead of night. Some time before leaving, we smeared our faces with ashes, a technique designed, he said, to catch the wild animals off guard, by convincing them we were of their kind. Next, round our ankles, we tied grasses I still don't know the names of, to ward off any snakes we met on our way. We followed a winding path that my uncle knew like the back of his hand, till, after a few kilometres, we reached a stream burbling between rocks. At the edge of the stream he gave a sign to show I shouldn't speak, not even whisper or squash a biting mosquito. A hundred or so metres from us a hind and a stag were drinking. I waited for my uncle to take up his position and shoot down at least one of them. But instead he knelt on the ground and began chanting words I didn't understand. The two grazing animals watched us from a distance, but seemed untroubled by our presence. Uncle Matété's prayer seemed to go on for ever, interspersed with names of people in our family like at school when the teacher was checking we were all present before starting lessons. Except that no one answered my uncle's name-call. The two deer listened carefully to his monotonous speech, nodding their heads in agreement every now and then. When the prayer was finished, the two mammals bellowed loudly then began to move off from the water, eventually vanishing into the depths of the bush. The silence in their wake was chilling. My uncle knew what I was thinking, and got in first:

âI'll explain tomorrow, for now just follow me, we need to find something to take back home. We can cross the river now, we've got permissionâ¦'

We went on deeper and deeper into the forest and when I turned around, Uncle Matété whispered:

âNever look over your shoulder in the bushâ¦'

âBut we'll get lost, we won't know how to get home again,' I worried.

âHave you ever seen anyone get lost in his own home?'

âBut what if it was a big house, like the white people's castles?'

âWell, the difference is, this is our castle, we know it, it doesn't just belong to one family like it does in the white people's land, it belongs to all the villagers.'

We came out into a clearing and heard a noise coming from the top of a palm tree. My uncle swung his torch towards it. It was a pair of squirrels, one on top of the other, absorbed in a courtship ritual which was shaking the leaves of the tree. The bang from my uncle's gun made my ears pop. Both animals had been hit with a single bullet. Uncle Matété picked them up from the bottom of the tree and put them in his game bag.

A bit farther on, an anteater was curled up in a ball in the middle of the path. This species is renowned for its poor eyesight, but as soon as the torchlight caught him, he lifted his snout and tried to make a run for it. Too late: my uncle had already taken aim and squeezed the trigger. The bullet blew out the creature's brains.

âRight, we can go back now, that's enough for this evening,' he decided.

It seemed a long way home. It felt as though the weeds were slashing at my legs, and leaving my uncle's untouched. I could hardly keep upright, and complained now of mosquitoes and other insects flying into my eyes. Some of these seemed to flash and then zoom in on me so fast I thought they must be shooting stars falling out of the sky. Uncle Matété told me to walk in front of him. After a few metres he noticed I was slowing us down. At this speed it would take us five or six hours to get back to the village. At first he teased me, calling me a town boy, then he lifted me over his head while I slipped my legs round his neck. My right foot rubbed against his well-stocked game bag, which he wore like a shoulder bag. Even in this more comfortable position I sometimes had to bend low to avoid the branches sticking out from the trees, and the little fluorescent creatures who must know I was just a town boy, the way they picked on me.

Back in the village I lay awake the rest of the night. I was in a sweat, haunted by visions of the hind and stag. I saw them standing there, the male with a human head, crowned with branched horns whose tips just touched the clouds, the female a little apart. The two of them spoke our language, and said my name. The pair had a fawn following after them now, and the little animal's head looked exactly like mine! What's more, he kept giggling for no reason, and his parents didn't stop him.

I was up early next morning, at dawn: I ran into my uncle's bedroom, while he was still snoring. He awoke with a start, and didn't seem in the least surprised at my bursting in so early:

âYou've come to tell me about the hind and the stag! You want to tell me you saw them in a dream?'

âYesâ¦'

âWell then! Now they know you! How did they appear to you?'

âThey were with their child, and the child had my face! He was laughing like a mad thing, I don't laugh like thatâ¦'

âI'd expect that, the child was happy to see you, because you and he are one body. The hind and the stag weren't just ordinary animals. The male is the double of your grandfather, Moukila Grégoire, and the female is the double of your grandmother, Henriette N'Soko. If I had killed those creatures when we were out hunting yesterday, your grandparents would be dead by now. Before you enter the bush you have to go and say good evening to the doubles, then they help us find our game. People who don't respect this ritual always come home empty-handed, or get lost in the forest. Or not lost exactly, but they get turned into trees or into stones by the spirits of the bush. When you're grown up, whatever bush you go into, remind yourself that spirits live there, and be respectful of the fauna and the flora, including objects that seem unimportant to you, like mushrooms, or the lowly little earthworm trying to climb back on to the riverbank. In our family we only hunt squirrels and anteaters, those are the prey given us by our ancestors, because the other animals, unless we are expressly told otherwise in our dreams, are members of our family who've left this world, but are still living in the next. Would you eat your mother, your father or your brother? I think not. I know these things sound strange to you, you've grown up in the city, but they are simple truths that make us who we are. Now, you mustn't eat hind or stag meat, because even if it didn't kill you, a part of you would disappear, the part we call

luck

or, rather,

blessing

.'

I gave a little cough behind Uncle Matété, as he stood there looking out at the Adolphe-Sicé hospital. He turned round and asked me very seriously:

âTell me truthfully: have you ever eaten hind or stag meat?'

âNo!'

âThat is a relief, nephew, you did listen to me, then! You can't imagine how I worried about you!'

We go back into the living room. Since he arrived unannounced, I've nothing to offer him. In the kitchen I find three eggs, which I break and throw into a pan. I break off three bananas from the bunch he gave me. While I'm busy making the food, I feel his presence behind me.

âNephew, what are you doing?'

âI'm making you something to eat.'

âNo, no, don't do that⦠In any case, I don't eat eggs, and you can't serve me the bananas I gave you!'

At a loss, I suggest we go and eat out in the Rex neighbourhood. He turns down my offer:

âI didn't come here for that, nephew. I simply wanted to make sure you were all right, that you hadn't eaten stag or hind meat in all these years. I introduced you to your animal double, the fawn you saw in your dreams when you were only ten years old. That little creature is still out there in the bush, he'll live as long as you, or you'll live as long as he doesâ¦'

âUncle, I know why you came: you want me to go and see my animal double in Louboulou.'

âNo, no, it's too far, I don't suppose you've got the time with everything you've got to do in the few days you've got left here. Your double will understand, but you must give him something, I'll pass it on to him when I go down there next monthâ¦'

âAh! I get it! How much?'

âNephew, don't you disappoint me, I know you live in a country where money is everything, but believe me, it's not the only thing that matters in this world. The thing that has kept you alive this far is without priceâ¦'

âWhat can I give to an animal I've only seen once in a dream when I was ten?'

âSomething that belongs to you, something of yourselfâ¦'

He digs in his pocket and takes out an empty test tube, the kind doctors use in hospital to take blood samples.

âPut your urine in there, I'll keep it in the freezer, then I'll go and pour it out by the stream in Louboulou where we were thirty-five years ago. The hind and the stag are gone now, your grandparents are dead, but their son, who's your age now, will still be there. He must smell your presence, your urine will be enough for him to continue to bless youâ¦'

I go into the bathroom, and come back with the tube full. This time he takes a bag out of his pocket and rolls the object up inside it.

âThat's perfect, nephew, now I must be on my wayâ¦'

I hold out an envelope, with twenty thousand CFA francs inside.

âNo, nephew, I didn't come to see you for that.'

âUncle, please, take it, it'll pay for your trip back homeâ¦'

He hesitates for a few seconds, lowers his eyes, and pockets the envelope:

âThank you, nephew.'

Last week