The Little Girl Who Fought the Great Depression: Shirley Temple and 1930s America

Read The Little Girl Who Fought the Great Depression: Shirley Temple and 1930s America Online

Authors: John F. Kasson

To Peter and Laura,

For the gift of their childhood, mature wisdom,

and sustaining love,

To William E. Leuchtenburg,

For his friendship, scholarship, and inspiring example,

And to Joy,

For everything!

CONTENTS

4

THE MOST ADORED CHILD IN THE WORLD

Epilogue: Shirley Visits Another President

Acknowledgments and Permissions

THE

LITTLE GIRL

WHO FOUGHT

THE GREAT

DEPRESSION

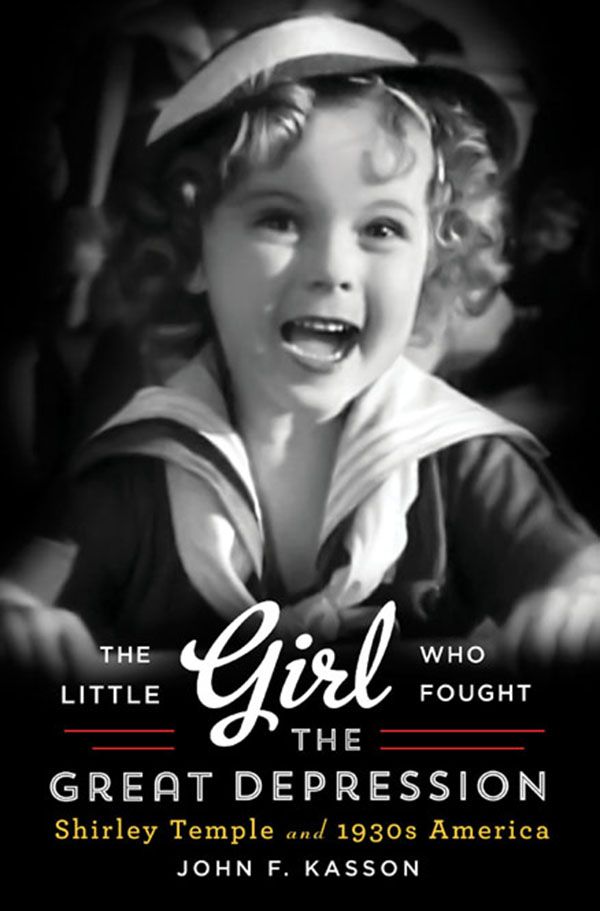

Smiling through the Great Depression: Shirley Temple, 1935. (Photofest/Twentieth Century–Fox)

H

er image appeared in periodicals and advertisements roughly twenty times daily, rivaling President Franklin Roosevelt and the United Kingdom’s Edward VIII (formerly Prince of Wales and later Duke of Windsor) as the most photographed person in the world. Her portrait brightened a poor black laborer’s cabin in lowland South Carolina, the mantel of the tumbledown house of a poor white childless couple in North Carolina, the living room mantel of preteen Andy Warhol’s house in Pittsburgh, the recreation room of Federal Bureau of Investigation director J. Edgar Hoover’s house in Washington, D.C., and the bureau of notorious numbers gangster Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson’s Harlem apartment. A few years later her smile cheered the secret bedchamber of Anne Frank in Amsterdam as she hid with her family from the Nazis.

1

Conventional histories of the 1930s draw their emblematic faces from the period’s distinguished documentary photographers, such as Dorothea Lange’s careworn woman known as “Migrant Mother.” Yet the most popular and cherished images of the period were smiling ones, and the most popular and memorable of all were of the child actress Shirley Temple. At a time when movie attendance knit Americans into a truly national popular culture, they did not want a mirror of deep deprivation and despair held up to them but a ray of sunshine cast on their faces. In fact, such conspicuous demonstrations of confidence characterized the Great Depression, as President Roosevelt extended the politics of cheer deeply into the private lives of citizens and Shirley Temple did so into the private lives of even the youngest consumers. The complex and paradoxical effects of these efforts are with us still.

The emotional resiliency embodied in the smiles of Shirley Temple, Franklin Roosevelt, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and others in this decade has been largely taken for granted. Yet such smiling figures repay close investigation. They yield important insights into the character of American life during the greatest peacetime crisis in American history. They have broader implications for modern culture as well. “We can see emotional expressions as a medium of exchange,” the sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild has written. “Like paper money, many smiles and frowns are in circulation.”

2

The circulation of a new emotional currency during the Great Depression formed a little-understood but essential part of the nation’s recovery, a sort of deficit spending with immense effects. In a time of great financial hardship, spending on amusements actually increased—eloquent testimony to its emotional necessity. Satisfying the craving of many deep in need of emotional loans and replenishments challenged political leaders and entertainers alike. The politician who succeeded most effectively was Franklin D. Roosevelt. The entertainer who did so most spectacularly was a little girl, Shirley Temple. Born in April 1928 in Santa Monica, California, to Gertrude and George Temple, Shirley began her film career at age three. Her performances attracted little notice until April 1934, the month she turned six. Then, with the release of Fox Film’s

Stand Up and Cheer!

, she catapulted to stardom. But what distinguished her from every other Hollywood star of the period—and everyone since—was how brilliantly she shone. For the next six years, before she left Twentieth Century–Fox in 1940, she made twenty-two feature films. Through four of those years, from 1935 through 1938, she was the most popular star at the box office both within the United States and worldwide, a record never equaled. At the end of this energetic period of performances (which would continue at a lesser pace through the 1940s), she was still under the age of twelve.

In all of her major roles in the 1930s Shirley’s central task was emotional healing. She mended the rifts of estranged lovers, family members, old-fashioned and modern ways, warring peoples, and clashing cultures. She accomplished these feats not by ingenious stratagems but by trusting to her inexhaustible fund of optimism. No loss ever troubled her for long, even the death of a parent or reversal of fortunes. No scolding matron or miser could dampen her mood. Money could not buy happiness, she repeatedly reminded audiences, and, although she often wore exquisite clothes and bounced between cramped quarters and palatial settings, riches never turned her head. She treated the lowly with kindness and approached the mighty without intimidation. Characteristically lacking one or both parents, she relied not on institutional charity (frequently personified by desiccated killjoys) but on the doting protection that she magically released from hardened soldiers, harried executives, vaudeville veterans, impeccable butlers, imperious aunts, grumpy grandfathers, courting couples—almost anyone with a heart. A tireless worker when the situation demanded, she could spontaneously tap-dance with a partner such as Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and sing a cheerful ditty or a tender love song. While gracious and polite, she delighted in subverting stuffy decorum by sliding down a banister or popping a paper bag in a sepulchral men’s club. She bubbled over with laughter, especially at herself. Amid gloom, she encouraged everyone to keep on the sunny side of life. Bromidic as philosophy, vacuous as social critique, her example was nonetheless immensely satisfying as entertainment. As such, it exerted a phenomenal appeal in an especially anxious decade, and it continues to remind us that Hollywood escapism in the Great Depression was never empty. Rather it brimmed with pleasures that both diverted and sustained moviegoers within the United States and through much of the rest of the world.

Shirley Temple holds an autographed portrait of FDR, November 14, 1935. (© Bettmann/Corbis)

Like other movie actors of the period, Shirley Temple functioned as a persona effectively created, owned, and operated by the studio for which she worked, and most of her waking life was devoted to playing the part of a girl whom fans would find irresistible. Even as the Roosevelt administration sought to curtail exploitative child labor practices, it made a major exception for child acting, and both FDR and Eleanor Roosevelt heartily endorsed Shirley. Children still held an important place in the economy, but increasingly as consumers rather than producers, and particularly as beneficiaries of adult spending. As the most famous and commodified child in the world, Shirley Temple played a pivotal role in this revolution. She became a cultural fetish, whose likeness and outfits were endowed with magical properties, even as her role in producing that fetish was obscured.

Not only were Shirley and her parents transformed by Hollywood’s star machinery, so too were her fans and their families. All came to view themselves and one another through the lens of celebrity. As a result, the rays of Shirley’s star penetrated the deepest recesses of family life, recasting the terms by which parents valued their own daughters and those daughters imagined themselves. Within a year of Shirley’s breakthrough in 1934, hers was the second most popular girl’s name in the country. Twentieth Century–Fox staged promotional events, such as Shirley Temple look-alike contests and birthday parties, to solidify her bonds with individuals, families, and even entire communities, as when twelve thousand members of an Illinois town signed a congratulatory birthday telegram to Shirley. She quickly became the most adored and imitated child in the world. In Cuba contestants vied for the accolade of “la Shirley Temple Cubana.” A Tokyo newspaper reported a young girl on the street discovered as “the Japanese Shirley Temple.” Throughout the country and around the world, using every ploy that they could devise, movie theaters joined with merchandisers to promote Shirley Temple’s latest film and licensed products. Her power and presence could be purchased in Shirley Temple dolls, dresses, underwear, coats, hats, shoes, soap, books, tableware, and similar items. Her face beamed from cereal boxes and cobalt blue plates and mugs. Ideal Novelty and Toy Company’s Shirley Temple dolls accounted for almost a third of all dolls sold in the United States in 1935. Sheet music of her songs, such as “On the Good Ship Lollipop” and “Polly-Wolly-Doodle,” led the sales charts. Newspapers around the globe bulged with Shirley Temple stories, as did movie magazines such as

Photoplay

,

Modern Screen

, and

Silver Screen

, each of which claimed a circulation of roughly half a million.

3