The Living Years

Authors: Mike Rutherford

The Living Years

Mike Rutherford

Constable • London

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Constable, an imprint of Constable & Robinson, 2014

Copyright © Mike Rutherford 2014

The right of Mike Rutherford to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

Interview extract on pp55–6 reproduced by kind permission of

East Grinstead Courier & Observer.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with references to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-4721-0981-1 (hardback)

ISBN 978-1-4721-1619-2 (trade paperback)

ISBN 978-1-4721-1035-0 (ebook)

Printed and bound in the UK

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

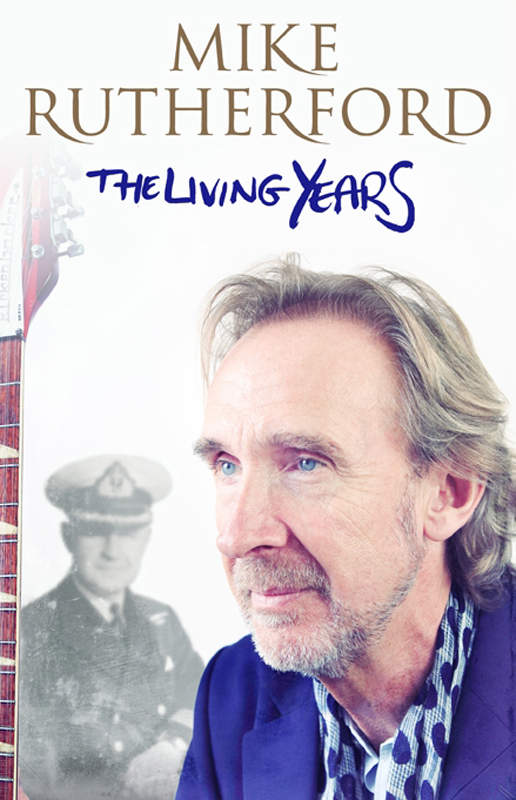

Cover Design and image: © Andy Vella

www.velladesign.com

To

Angie, Kate, Tom and Harry

I was in a hotel room in Chicago when the phone rang at 3 a.m. It was Angie: ‘I’ve got some bad news – Dad’s died.’ Time really does freeze at moments like that and your heart plummets. Mum had called her: ‘Angie darling, Dad’s dead. I’ve poked him with my stick and he’s not moving: he’s definitely gone.’ Mum was in a wheelchair and very immobile – she and my father slept in twin beds – and the phrase was exactly like her. I could almost hear her voice.

At that moment I couldn’t think of anything to say or even discuss arrangements. I was too much in shock. After I hung up I stood by the hotel window and looked down at the car headlights. I was on the thirty-fifth floor and it suddenly seemed incredibly quiet and very lonely. I felt very distant from anything that was happening down on the street – I just didn’t feel part of the world.

We were in the middle of a six-show run in Chicago playing to 20,000 people a night and were less than a month into our year-long tour. If I’d wanted to fly back to England I knew that the band and our manager Tony Smith would have supported me, just as we had always accommodated each other musically. But I also knew that there was nothing I could really do in Farnham. Mum had Angie and my sister Nicky to look after her and my father had taken care of all the funeral arrangements. So Tony Smith and I sat down and made a plan. In two weeks’ time I would fly overnight to England for the funeral and after the service I would fly straight back by Concorde to California for a show at the LA Forum.

The next two weeks were surreal. I found I could go on stage and get lost in the music for two-and-a-half hours, but then the show would end and the realization of what had happened would hit all over again. There was a sense of security, of safety, playing with Tony and Phil but my own emotions and my father’s death were something we didn’t discuss.

There were times in my life when I felt guilty not talking about my feelings, but that was just how I was brought up. I think public school was a large part of it but it was also generational: my father and I belonged to a time when sons didn’t tell their fathers they loved them. I’d never told my dad that I loved him and my biggest regret was not telling him what a wonderful man he’d been in my life.

I arrived in England on 13 October 1986 and went home briefly to see the children. I then drove with Angie to the funeral service in Aldershot. The night before I’d been on stage in front of thousands of people, and now I was in a car on the way to an English church to say goodbye to my father for the last time. After that, I would be flying back to LA – I knew then I needed some help. I asked Angie if she would fly back with me just for one night. Someone drove to our house to pick up her passport while we were in the church and then it was straight to Heathrow, where we boarded Concorde for the first leg of our journey. Angie was still in her funeral dress and only had her handbag.

We arrived in New York and a car was waiting on the tarmac to take us to the private jet that would fly us to LA. I think it was then that the enormity of it all really struck me. As we flew west, keeping up with the sun, the day seemed endless and yet all the time I was aware of leaving that church in Aldershot further behind, while LA was getting closer. It seemed very still on that plane – it was just us and a couple of crew – and the sun still wasn’t setting. I felt as though I’d lost my compass point.

I found out later that two of the people in the audience that night in LA were Elton John and Gary Farrow, his PR. They both knew what was happening and spent the time before the show discussing whether I was going to make it back or not. The band were trying to decide which songs they could play without me or even if they would have to cancel the show. I arrived with twenty minutes to spare thanks to a police escort from the airport.

It may sound self-serving to say that I played that show for my father but when I heard those eerie chords to ‘Mama’, that primal, basic beat, that’s what I felt I was doing. My father had always taught me that if you had an obligation, you fulfilled it – it was as simple as that. That night I was giving something of the right spirit, and I think he would have approved.

When I went to bed and Angie eventually fell asleep, I couldn’t stop thinking about how bizarre the whole thing was. I’d buried my father in the morning and then travelled backwards in time to play the show. Somehow I also felt that my father had gone on a journey too – I wasn’t quite sure where either of us were at that point.

* * *

My father’s death hit me the most six years later, following my mother’s death in 1992. My sister Nicky cleared out their house and sent me three weathered, leather-bound trunks belonging to my father.

I was still reeling from my mother’s death and the fact that we had to sell my parent’s first and only home in Farnham. It was the end of an era and I didn’t really feel ready to look into the trunks in case they stirred up emotions I wasn’t sure I could handle. I’ve always been one to keep my emotions hidden away. I put the trunks in the attic above my studio and that’s where they remained untouched for a few years.

I’m not sure when the time is right to deal with the past but it wasn’t a calculated thing – I was in my studio a few years later having a writer’s block sort of day, and my mind started thinking about the trunks. The next thing I was up there wondering which one to open first, as there was also one belonging to my grandfather. I decided to open my grandfather’s trunk and one of my father’s at the same time. The thing that startled me the most when I lifted the lids was the military precision – the way everything was so neat and tidy. In my grandfather’s case all of the papers and files were bunched together with elastic bands, while in my father’s case all of his paperwork was neatly put in plastic folders. I had a shock of recognition as I’ve always surrounded myself with plastic folders – and I’ve never even been in the military.

In these folders was a mixture of naval histories from Dartmouth, memorabilia from the wars, his medals, CBE, Distinguished Service Order certificates and his medical history, and his sword was also in the trunk. In my grandfather’s trunk there was similar stuff but I also found two of the books he had written:

Soldiering with a Stethoscope

and

Memoirs of an Army Doctor

. There were great reviews amongst his papers, praising Colonel Rutherford and the publishing deal he had landed. My father’s trunk contained a manuscript of his own memoirs along with a very positive and generous letter from David Niven, from whom he’d obviously sought an opinion (my father was a fan of Niven’s memoir,

The Moon’s a Balloon

). However, there was also a publisher’s rejection letter saying there was ‘not very much demand for military history these days and so I am sorry we cannot accept it’. I felt my father’s disappointment.

Last year my sons took my father’s manuscript and had it made into a beautiful leather-bound book. They gave it to me for Christmas – I was completely overwhelmed. I may hide my emotions pretty well but it was hard on that day. I sat down and started piecing together my father’s life, and read his memoir from cover to cover. I felt so proud not only of my father’s naval career but of the legacy he left me.

In May 1906 I was born in a London nursing home, my father then being stationed in Chelsea Barracks as Medical Officer. Having joined the Royal Army Medical Corps from private practice, he had gone off to the South African War, at the end of which he had married my mother who belonged to one of the old Cape families, the Cloetes, who had arrived in 1652 in South Africa and had lost no time in increasing their numbers.

My father was born into the age of empire: archdukes, emperors, a map of the world that was coloured pink. The seas were ruled by Edward VII’s Navy, which ‘had countenanced no rival since the Battle of Trafalgar’, and households like my father’s were ruled over by iron-fisted nannies.

My father’s travels began aged ten when his father, my grandpa, returned to South Africa. Nanny came too – although I’m not sure how happy she was about it:

We arrived at Durban and, disembarking, I had my first delighted ride in a rickshaw, a two-wheeled vehicle drawn by a Zulu between the shafts. He wore decorative clothing, though not much of it, and a headdress of horns. From time to time he leapt in the air with a blood-curdling yell, almost spilling his passengers over the back. I could not have enjoyed anything more but Nanny, who shared the general national view in those days that the black races began at Calais, was most put out by such goings on.

Three decades later my father was back in Durban again, which is where he met my mother, Anne: at the time he was Acting Captain of the heavy cruiser

Suffolk

, which had docked there for a refit. He saw my mother at a charity dance and they got married six weeks later: given that my mother was always the impulsive one, it seems odd that it was all so quick. In any case, the happy couple enjoyed a six-day honeymoon before my father sailed off again, this time for Trincomalee in Sri Lanka. They didn’t see each other again for ten months.

My parents were reunited in England after VE Day, my mother having sailed over on a troop ship and my father having been appointed to a position in the Admiralty, which was situated on Horse Guards Parade in Whitehall. However, by the time my mother was expecting my sister, Nicolette, in 1947, my father had been appointed Chief of Staff to the Naval Representative of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Australia. It was decided that my mother should go back to Durban for Nicky’s birth and only travel the rest of the way to catch up with my father afterwards. This meant that Dad didn’t know he had a daughter until a cable message was rushed up the gangway of his ship in Adelaide.

When my father’s term of duty ended in 1949 my parents and sister moved back to England. My father returned to his job in Admiralty and found a house to lease in Chertsey, Surrey, and that was where I was born on 2 October 1950. They chose not to go for the less is more option when choosing my names, so I was christened Michael John Cloete Crawford Rutherford. Less than two years later Dad was off again, this time to the Korean War.

My father was eight years old when he watched his own father go off to the First World War carrying field glasses, a sword and a revolver. Being eighteen months old I don’t remember what Dad was carrying when he left for the Far East but I do remember the day, two years later, when he came back: he asked how many teeth I had and then let me crawl all over his car – both good opening moves, I thought.

In fact, it was all going well until bedtime, when I began to get a bit suspicious: where was this strange man’s home? Surely it couldn’t be with us?

Apparently, it was.

I can clearly picture my father coming into my room at dusk to say goodnight to me, his silhouette at the end of the bed. He was a big man – not quite as tall as I ended up, but big – yet he didn’t seem scary.

I still had my doubts about whether he would disappear again overnight, though, and so kept getting up to check on his whereabouts. Eventually my parents gave in and moved my bed into their room so that they could get some sleep.

My father was always smart and he always had good posture: even out of his Captain’s uniform it was his posture, his presence, which impressed people about him. Wherever he went – into a restaurant or a shop or a stationer – he commanded respect: people were polite and courteous. He was also always punctual, methodical and orderly.