The Lonely Sea and the Sky (12 page)

Read The Lonely Sea and the Sky Online

Authors: Sir Francis Chichester

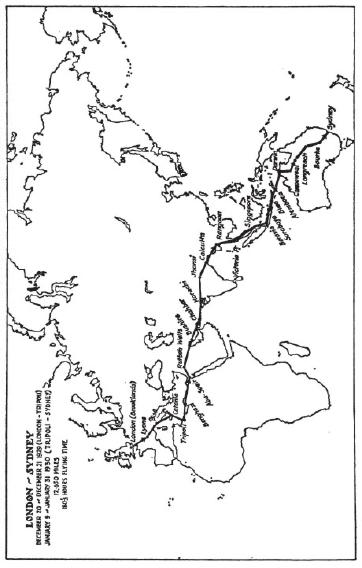

After refuelling with petrol and oil I cleared the Customs and collected my journey log-book,

carnet de passage,

licence, and my passport with endorsements for seventeen countries, and was ready to leave. Walking near a hangar I asked a stranger for some information. When we came under a light he said, 'Aren't you Chichester? Don't you know me? I'm Waller of Hooton. I shall always remember your turning up at Liverpool in a new machine without a compass and with that ridiculous map of yours.' He had just flown down himself in his own aeroplane. Had I been for any more flights since then? 'Yes, I made a flight round Europe.'

carnet de passage,

licence, and my passport with endorsements for seventeen countries, and was ready to leave. Walking near a hangar I asked a stranger for some information. When we came under a light he said, 'Aren't you Chichester? Don't you know me? I'm Waller of Hooton. I shall always remember your turning up at Liverpool in a new machine without a compass and with that ridiculous map of yours.' He had just flown down himself in his own aeroplane. Had I been for any more flights since then? 'Yes, I made a flight round Europe.'

'Great heavens! But you've only just got your licence, haven't you? Perhaps you're going to fly home now,' he added, jokingly.

'Yes, as a matter of fact I am.'

I had not talked about my proposed trip for fear of failure and being laughed at.

'You're not really!' he said. 'When are you starting?'

'In six hours.'

He was silent for some time.

I ate dinner in a panic. When the porter told me I was wanted on the telephone I got hot and cold with fear that it was something which would stop me. I gasped with relief when it turned out to be the Meteorological Office, telling me that I must not land at Grogak, Rembang, Bima, Reo or Larantoeka in the Dutch East Indies because they were flooded. I could not worry about that. I was up at 1.30 a.m. and ate bacon and eggs.

At 3.15 a.m. I took off across the grass field. This was the first time I had taken off with a full load up. The aeroplane was carrying its own weight in payload. I thought this was the reason for the long and horribly bumpy take-off, but actually the ground, frozen hard, had ripped open a tyre and tube. As soon as I left the ground I felt the tremendous thrill of being off to Australia. The four exhaust stubs belched bluish flames against the night sky. I wobbled about at first both in yaw and pitch, for this was the first time I had steered a course at night. Luckily, I had moonlight at the start, and began to pick out the fields below. I could see the broad bands of hoar-frost along the lee of the hedges. I kept on trying to fly steady and level. I had no blind-flying instruments, and the horizon was vague and indefinite. I set about trying to read the drift, another thing I had not had time to practise. Leaving the coast and flying off into the murky darkness was another exciting moment. The moonlight was cut off by a layer of cloud and the horizon had completely vanished. All I could see was a glint on a small patch of water directly beneath the aeroplane. I hoped to keep roughly level by means of the altimeter, and when I looked at it, the dial was rotating without stopping. I had nothing to judge the height by except the patch of sea underneath. If the waves were small I might be only a few feet above them; if large, I might be thousands of feet up.

I had expected to cross the Channel in about fifteen minutes, and when I was still over water after three-quarters of an hour I began to feel lost. The truth was that I was making a hash of my first night navigation. I had over-estimated the drift, and thought I had crossed the south coast at Folkestone. When France did not show up as expected, I wondered if I was heading into the North Sea. If I had been able to study my map, and use a ruler and protractor, I would have seen quickly what was happening, but there was no light in the cockpit, and I did not like to stop looking out while I worked a torch with the map and instruments. Gradually, I reasoned that the North Sea was an impossibility and that I was headed south towards Dieppe.

At last, an hour after leaving England, a high, whitish cliff loomed up just ahead. I flew along beside the dim, ghostly white face for some 5 miles, determining the compass bearing of its direction. There was only one 5-mile piece of coast running in this direction â I must be north-east of Dieppe. I worked out a fresh course for Paris from that spot, allowing ten degrees for drift; but the wind had dropped altogether, so I was set to the west of Paris. As a bleak, dismal, November grey crept into the sky, I was cold and cramped and attacked by an overpowering desire to sleep. I got a map fix, and worked out a fresh course for Lyon. Dawn broke, the earth was white with frost, the canals and patches of water covered with ice. Smoke drifted lazily above the chimney tops. After seven and a half hours in the air I landed at Lyon. It was a good landing, but the machine tried to slew round at the end of its run because of its flat tyre. I ran 300 yards in my big sheepskin boots, then had an enormous omelette with a bottle of red wine. The tyre was mended for me, and I got away after one and three-quarter hours on the ground.

Climbing with full load to 10,000 feet in order to cross the Alps seemed to take an age. I kept on looking at my watch, and wondering whether I could reach Pisa before dark. I flew over the Cenis Col with 3,000 feet to spare and it was a great relief to have crossed the Alps in smooth air; also to be flying faster on the long descent to Turin after the slow, tedious climb with full load. Everything went well until I ran into rough air at Genoa. Whizz! Whop! Bump! Each bump sent a shower of petrol into my face from the vent of the cockpit tank in front: I tried flying over the sea, but it was worse there. I was scared stiff that the wings would fold up. I bolted back to the mainland again, and was hurled this way and that as I climbed with throttle wide open at the steepest possible angle against the down-draught coming through a col in the hills. The slots clanked each time an extra strong bump stalled the aeroplane. I only just managed to clear the col. Then I flew down a valley parallel with the coast. At first I tried to climb in the hope of escaping the bumps, but each time I gained a few hundred feet a violent downwash of air forced me down again. I felt as hot as if I had just run a mile race.

Night fell, and at last the air became calm again. I plodded on to Pisa, where I could see the aerodrome a long way ahead splendidly lit with a searchlight signalling me. I flew up to it, and cut my motor three times to let them know on the ground that I had arrived, and then shut off to land. Close to the ground I found that it was not an airfield, but bright lights illuminating a long, L-shaped hoarding, half a mile long at the corner of two streets. The searchlight was a powerful beam from a motorcar.

I soon recognised the airfield as a big black space, but there was not a single light showing except from some barracks at one end. My first shot at landing in the dark was a dud; I bumped and went round again. However, at my next shot I landed well and started to taxi in, but the wheels got bogged in the mud. A swarm of soldiers seemed to spring out of the ground and pushed the

Gipsy Moth

out of the mud, breaking one or two of the ribs in the leading edge.

Gipsy Moth

out of the mud, breaking one or two of the ribs in the leading edge.

I asked in French about the lights, and they said that they had expected me to circle for half an hour while they went to find the light operator. The Italians were extremely kind and helpful, but everything had to be discussed at great length. It took four and a half hours of solid talk and argument before I had refuelled, checked over the motor and satisfied the Air Force, Customs and police authorities. They lent me a campbed and I tried to sleep at 10 o'clock, but I was too tired. I had started tired, had put in a strenuous 20 hours, of which 12 had been spent flying 780 miles. I only had two and a half hours sleep before getting into the air again at 1.45 a.m. I took off in the dark with no lights on the airfield, so that I had landed and taken off from an airfield that I had never seen. It was a lovely, fine night when I reached Naples. The sky became overcast, and I was flitting along under the ceiling of a low, wide-roofed cavern. Vesuvius was a magnificent sight with dark, billowy smoke rolling slowly from the cone, and a million sparkling, twinkling lights clustering round the bay at the foot of the volcano. I flew over the Gulf of Salerno into pitch darkness. I could see nothing ahead or below. Presently, flashes of lightning from a black storm cloud lit up the whole area. I was able to dodge this, but later flew into a rain-cloud. I could not see six feet ahead, and glided down until I could distinguish land by its utter blackness in comparison with the less black sea.

I was now flying beside a barren, mountainous country, apparently uninhabited, because there was not a single light visible anywhere. Daybreak was approaching and as the tatty grey storm clouds began to outline the mountains, sleepiness became an agony. I moved anything I could, waved my arms, jumped up and down in the seat, stamped my feet. If I jumped up I was asleep before I landed in the seat. I was primitive man looking at a stark, primeval scene, the black masses of towering mountains, the rugged grey precipices of rock dropping sheer into the sea and the dull surface of the sea flitting out of sight under threatening cloud. Each time I slept I heard separate motor explosions, usually about four, with an increasing interval of silence between them. Then silence, and I woke with a jolt, petrified with fear that the motor had stopped. The first few times this happened I felt certain it had; it was worse when I realised that the motor was still firing steadily at 3,600 times a minute. I no longer had the fright that kept me awake for a few seconds. I took off my flying-helmet and stuck my head into the slipstream. I tried watching the cliffs, but my eyes would not align properly; I saw double. At last day came; I had been flying for six hours. I was tempted to look for one of the three emergency landing-strips on the beach where it widened, for the desire for the aeroplane to roll to a standstill so that I could loll my head against the cockpit edge and go to sleep was overpowering. I had already passed the first of these landing-strips; when I came to the second it was half washed away. Then, at the toe of Italy, sleepiness abated, and I flew on for another age across the straits and on to Mount Etna, looking enormous and solid in her snow cap. I landed at Catania and was stuck there for three hours. Petrol and a Customs officer had to be fetched from the town. When I had everything ready I found my journey log-book was still in the town and I had to wait another hour for it to turn up.

I managed to get in fifteen minutes sleep, which was a godsend. It was obvious now that I could not reach Africa before dark, so I asked carefully about night-landing facilities at Homs. I was assured that the airfield there had everything that could be desired in night-landing facilities. Then I flew over Malta. I thought of stopping there, but I had made up my mind to reach Africa in two days. I flew through a curtain of stinging hail, and a terrific flash of lightning near by made the aeroplane rock. After that, most of the 285-mile sea crossing was in fine weather. The sun set magnificently.

I was thrilled by my first sight of Africa, but surprised to see by the twinkling lights that the terrain sloped steeply up from the sea, whereas I had expected a broad, level sand desert. When I reached Homs it looked small, no more than a village, and there was no sign of an airfield. I thought I had made a mistake, and flew on for 6 to 8 miles to the next promontory of the coast. Looking back, I saw a large reddish light, stronger than any other. When I reached the headland there was not a light in sight ahead, so I returned to investigate the red light. I was disgusted to find that it was a big bonfire in a deserted area of the country. I did not realise that it was lit to indicate a landing-place. I decided to head for Tripoli, 70 miles to the west. If I did not find a landing-ground before that, I knew that Tripoli was an Italian air force base.

There were no lights visible along the coast. Presently I flew into cloud, and could see nothing. I did not like it, with no blind-flying instruments, and no altimeter. Later, I spotted a searchlight ahead, flashing at regular intervals. I thought it was an airfield signalling to me, and it cheered me up. After flying on another 20 miles I could see a magnificent cordon of light, and thought that the airfield was really well lighted up. I began to sing. Later the light appeared to be just as far away. When at last I arrived I found that the airfield was the harbour, and the searchlight was the lighthouse, on the Mole. I circled the town in the dark, but could not see any airfield. Then a starry light flashed 10 miles to the west of the town, and I flew over to that. I could see no airfield boundary lights, and glided down close to the ground, when I found that a motor-car was switching its lights on and off, trying to overtake another one.

Then an unmistakable searchlight appeared in the sky to the east of the town. There were no boundary lights, just the one searchlight which was lowered to the ground as I approached. It was pointing right at the hangars. If I landed along the beam, I should be heading right for the hangars, and I judged that there was only 200 yards between the light and the hangars. I could not be sure of a good landing in the dark after so long in the air. I circled the field, and could see a fine square of flat ground, surrounded by trees. I decided to land on this, short of the searchlight. I glided in steadily until suddenly, wonk! I was jolted forward and found myself held into the cockpit by my harness. The

Gipsy Moth

had tipped on to its nose. I had an empty feeling of utter failure; it was the end of my flight and my foolish dreams. I was aware of the dead silence that succeeded the motor roar, yet the rhythmic engine beat continued, not only in my brain but in every part of my body. I scrambled out of the cockpit, stepped on to one of the inter-wing struts and from there jumped to the ground. To my amazement I landed with a splash. 'Good God! I'm in the sea.' I listened but could hear no waves. The water only came to my ankles. I started towards the searchlight; a few steps and I floundered on to my knees. Then, stumbling forward, I touched a bank, and climbed up it (it was only a foot high). I felt like Puss in Boots in my long sheepskin boots. I stopped there, filled my pipe, but could not get the cigarette lighter to light.

Gipsy Moth

had tipped on to its nose. I had an empty feeling of utter failure; it was the end of my flight and my foolish dreams. I was aware of the dead silence that succeeded the motor roar, yet the rhythmic engine beat continued, not only in my brain but in every part of my body. I scrambled out of the cockpit, stepped on to one of the inter-wing struts and from there jumped to the ground. To my amazement I landed with a splash. 'Good God! I'm in the sea.' I listened but could hear no waves. The water only came to my ankles. I started towards the searchlight; a few steps and I floundered on to my knees. Then, stumbling forward, I touched a bank, and climbed up it (it was only a foot high). I felt like Puss in Boots in my long sheepskin boots. I stopped there, filled my pipe, but could not get the cigarette lighter to light.

Other books

5 Buried By Buttercups by Joyce, Jim Lavene

Annette Vallon: A Novel of the French Revolution by James Tipton

The Turtle Warrior by Mary Relindes Ellis

The Do It List (The Do It List #1) by Jillian Stone

The Ghost in the Big Brass Bed by Bruce Coville

To Wed a Rancher by Myrna Mackenzie

Bold & Beautiful by Christin Lovell

Imperfect Birds by Anne Lamott

A Cowboy Under the Mistletoe by Vicki Lewis Thompson

Someone Like Her by Sandra Owens