The Lonely Sea and the Sky (35 page)

Read The Lonely Sea and the Sky Online

Authors: Sir Francis Chichester

Taking not the slightest notice of what I said, he directed the old woman to work the sampan across my anchor rope, which the coolie fished up with his boat hook. Then they lifted my anchor. How that old woman had handled the sampan by herself in that wind had been a marvel to me; now she had the seaplane as well, and it takes a man's utmost strength to hold the seaplane in a strong wind. She stuck grimly to her scull, but we drifted back steadily, right into the middle of the shipping fairway. I implored the white man to drop my anchor, but he jumped about excitedly, waving his arms and ignoring me. He did at last realise that we were going to end up on the opposite shore, and then he did drop my anchor, and returned to the launch, leaving me right in the fairway, with large steamers passing one after the other making a strong wash. Presently he came back, again from the side. I could do nothing; with all my shouting in the strong wind, my voice had died away to a whisper. There was a tearing noise as the stem of the sampan penetrated the fabric of the wing tip. 'Can't stay here,' he cried, 'shipping-dangerous â not allowed.' The coolie picked up my anchor rope again with his boat hook, the launch backed down to the sampan, and passed a line to it which the mandarin fastened to my anchor rope with a number of granny knots. The launch moved off at full speed across wind. The seaplane, when pulled from the side, glided forward in the strong wind just as a kite rises into the air when the string is pulled, and was soon broadside on to the wake of the launch. The end of the float began to twitch under the strain, and I expected to see it pulled off. I rallied my voice for some last desperate yells, but no one took the slightest notice. Fortunately the anchor rope snapped, and I drifted sternwards without an anchor. The launch chased me and threw a line. With the mandarin absent on the sampan, they listened to me, and everything was arranged in a few moments. We began crabbing across the wind, dead slow, towards the fleet of junks. Every time the wing started to lift at a gust, I ran out along the spar to keep it down with my weight. At last, when we were out of the fairway, and somewhat sheltered among the junks, they shouted to me to come aboard. But the white mandarin had arrived in the sampan, and with flamboyant gestures, his hair streaming in the wind, he exhorted the old lady to bear down once more on the seaÂplane, downwind. With the hole in the fabric, the wing tip buckled, and several ribs in the leading edge smashed, besides one or two lucky escapes, I had had enough of him, mandarin or no mandarin. When he came close enough, 'You bloody bastard,' I said shaking my fist, 'if you barge into me again, I'll wring your neck!' This he listened to. 'What do you want, then?' he demanded.

'Come up from astern, you bloody fool,' I said as the sampan struck. Fortunately the old woman's skill was marvellous, and with my frantic shove from the float the sampan passed round the wing with only slight damage to the tip. In the flurry my hat blew off, and went bowling over the water. At last he came up from astern where, of course, the old woman brought up the sampan with the greatest of ease. 'And now,' I said, 'perhaps you will tell me who I have had the honour of dealing with all this time?'

'I represent the

North China Daily News

. I am a South African and a globe-trotter like yourself and a keen airman like yourself.'

North China Daily News

. I am a South African and a globe-trotter like yourself and a keen airman like yourself.'

On board the launch I met Colonel Thoms, who was a big, tall New Zealander in command of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps, Palmer, the Shell man, and a China Police officer. We debated what to do with the seaplane. Palmer said that it would be difficult to guard it there, and that it would take one and a half hours to get down the river by launch. I asked why he did not come down by motor-car. Thoms said, 'You can't motor anywhere here. There are no motor roads, and it is not safe to leave the town.' Here the old woman, her withered face wreathed in a friendly smile, manoeuvred her sampan alongside and returned my hat. She had gone off by herself and rescued it while we talked.

It was decided that I should fly up-river to the Shell (Asiatic Petroleum Company) store and jetty, half way back to Shanghai. Before getting into the sampan to return to the seaplane, I drew Palmer aside. 'Can't you come in the sampan instead of that chap?' I asked. 'It's pure luck that my plane is still intact; why didn't you come in the first place?' 'I didn't like to, because he is a flying man, and knows all about it.'

Palmer talked Chinese fluently and I was quickly back in the seaÂplane without any trouble. When I opened the throttle to take off I was only 170 yards from the river bank ahead of me, but the seaplane took off easily enough some thirty yards short of the bank. I circled to have a good look at the take-off scene, recalling all the long hair-raising attempts to get off during the voyage before the floats were mended. I came down by the Shell jetty and the seaplane was hauled up a grass bank beside it, with each wing tied down to oil drums full of water. By the time all this had been done it was dark, and we trod across a number of sampans to a jetty where the shadows were pitch black. 'Keep together,' said Thoms, 'they have a habit of sacking a knife into people here, and holding the body under water until all is quiet.' After a long wait beside a road while I tried to keep the reporter from sitting on the bundle containing my one suit, Palmer at last secured a car, and Thoms took me to stay at his house.

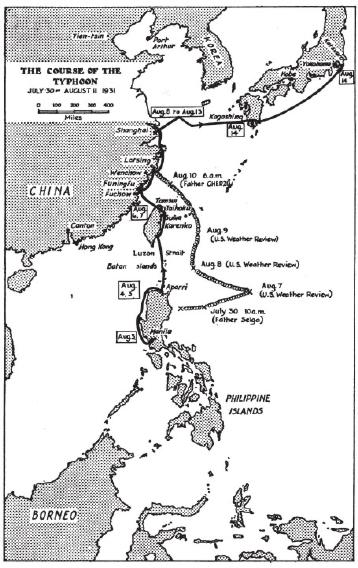

In the morning, my first concern was to find out about the weather over the Yellow Sea between China and Japan. The sea crossing was 538 miles, and if I should meet a headwind of 20mph I should be forced down short of Japan. The only way to get a weather report was to go to the Observatory of the Jesuit convent at Siccawei. This was outside the International Settlement, and I spent the whole of the next day travelling. First we hooted our way yard by yard through narrow alleys barely wide enough for the car, with cries from coolies, jingling of rickshaw bells and Chinese chatter continually in our ears. Thoms's Chinese chauffeur was lucky to run 10 yards without the human swarm closing round us and forcing the car to stop with a jerk. At last we reached the convent, which stood in a deserted old-world garden, with mossy stone flags. I waited in a cool, silent, stone hall, while a priest went to find Father Gherzi. He was a thin tall man, with a slender high-browed head, and a narrow black beard. He wore a long black robe, under which appeared two enormous black boots. He was impatient, impetuous and clever. In a rapid, emphatic way, he said that there was a typhoon centred east of Formosa, that it was travelling fast straight for Shanghai, that it was impossible for me to leave for Japan because of a 35mph headwind, and that I must secure my seaplane at once. After my experience the day before with the emphatic reporter in the sampan, I started cross-examining Father Gherzi about this weather. He showed clearly that he resented this, and that he thought me a fool.

Scared for the survival of the seaplane, I returned to Thoms's office as soon as possible to find the best shelter for my

Gipsy Moth

. Looking for the RAF Intelligence Officer, we visited the long narrow bar of the Shanghai Club, which ran deep into a building like a straight high passage. It was full, and I received a number of remarkable suggestions for saving the seaplane. On looking back, the best would have been to fly west-north-west â away from the typhoon to Peking â a suggestion that came from Paddy Fowlds, an ex-RAF pilot, now with Shell in China. But I didn't want to go so far inland, and at last we located the RAF Intelligence Officer, who said, 'Had I tried the seaplane hangar?' 'What seaplane hangar?' 'The North China Aviation Company has a big hangar beside the river with a concrete slipway.'

Gipsy Moth

. Looking for the RAF Intelligence Officer, we visited the long narrow bar of the Shanghai Club, which ran deep into a building like a straight high passage. It was full, and I received a number of remarkable suggestions for saving the seaplane. On looking back, the best would have been to fly west-north-west â away from the typhoon to Peking â a suggestion that came from Paddy Fowlds, an ex-RAF pilot, now with Shell in China. But I didn't want to go so far inland, and at last we located the RAF Intelligence Officer, who said, 'Had I tried the seaplane hangar?' 'What seaplane hangar?' 'The North China Aviation Company has a big hangar beside the river with a concrete slipway.'

We could get no answer on the telephone, so Palmer took me up to the hangar in a launch. The slipway was on a lee shore with a strong wind blowing on to it at an angle. The hangar was also closed up and locked, but in any case it would have been impossible to get the seaÂplane to it in that wind. I had to leave her where she was that night.

Next morning Father Gherzi looked worried. The typhoon had destroyed 2,000 houses in the Ryukyus, the string of islands between Formosa and Japan. The Japanese had refused me permission to fly near these, and it was because of this that I was now in Shanghai facing the sea crossing to Japan. Father Gherzi told me that it looked as if the typhoon was going to curve and pass close to Shanghai to the east; that it was gathering speed; and that I must make my aeroplane secure. How was I to do that? In this whole vast city I could not find anywhere to shelter one small seaplane.

I went down to my

Gipsy Moth

, pulled her farther up the mud, and raised the float heels so that the wind would press the wings down instead of lifting them up. Next morning (10 August) Father Gherzi said that the typhoon was centred at 27° N., 123° E., which was 150 miles south-east of the bay where I had alighted when on the way up from Formosa. It appeared to be curving towards the coast, to pass inland, but that was unusual in August, and it seemed more likely to recurve itself and make directly for Shanghai. That day the steamer

Waishing

was wrecked in Namkwan Harbour, and the

Kwongsang

went down with all hands at Funingfu, my landfall on arriving from Formosa. The typhoon had travelled 360 miles in a day. Father Gherzi expected the wind to increase to 50mph that afternoon.

Gipsy Moth

, pulled her farther up the mud, and raised the float heels so that the wind would press the wings down instead of lifting them up. Next morning (10 August) Father Gherzi said that the typhoon was centred at 27° N., 123° E., which was 150 miles south-east of the bay where I had alighted when on the way up from Formosa. It appeared to be curving towards the coast, to pass inland, but that was unusual in August, and it seemed more likely to recurve itself and make directly for Shanghai. That day the steamer

Waishing

was wrecked in Namkwan Harbour, and the

Kwongsang

went down with all hands at Funingfu, my landfall on arriving from Formosa. The typhoon had travelled 360 miles in a day. Father Gherzi expected the wind to increase to 50mph that afternoon.

At 4.30 p.m. the typhoon gun was fired, and I went off down the river in a launch to stand by the seaplane through the night. I had one hope. The seaplane would be quite safe in a 100-mph wind if it was facing into it in a flying position. Such a wind would give the seaplane a lift equal to a ton's weight, so that if I could face the seaplane into the wind, and weight it down with a ton, it should ride out the typhoon. Filling the floats with water, as I knew from bitter experience, was the best way to weight it down, but it would not be possible after that to change its heading if the wind changed direction. I had the seaplane moved to the lee of a wall and the eyebolts in the wings secured to four oil drums. Then I removed all the bilge plugs so that when the tide rose, the floats would fill with water. The caretaker put me up for the night in the houseboat in which he lived. Every time I woke during the night the wind was blowing unchanged in strength, and in the morning it was still the same. Suddenly I thought, 'What a weak fool I am to be sitting here like a paralysed rabbit!' I went back to Shanghai by the first launch that passed, and sought out Father Gherzi. The typhoon had struck the coast at the bay where I had alighted among the junks, and was moving inland, but was expected to curve northwards for Shanghai. I told him that I was going to leave Shanghai next morning, typhoon or no typhoon. A wind that would prevent my reaching Japan would be favourable for a flight to Korea. If, after five hours over the sea, I took a sextant shot and found that I had not enough petrol to reach Japan, I would turn north and fly with the wind. I could do this even if the wind was 60mph. I expected him to tell me curtly not to leave, but he said only, 'Very well.' Then he begged me not to leave until he had reports from Korea and Japan in the morning. But I could not wait for these reports. I had to leave Thoms's house at dawn if I was to reach the seaplane by 7 a.m. and take off by 9 a.m. There were no telephones, or roads to the seaÂplane. Then I had an idea, and Paddy fell in with it. This was that I would take off, and fly back up the river; Paddy would get the latest report from Father Gherzi, and signal to me with a flag from the top of the Shell building as I flew past. If the wind was more favourable below 5,000 feet one flag; above 5,000 feet two flags; too dangerous for me to leave, three flags.

When I got back to Thoms's house I was told by Daly that I had been taken to the wrong hangar on Saturday; that one belonged to the Chinese army; the American Company's hangar was farther upstream, and they had waited for me there with a skilled launching crew.

In the morning, after the comprador of the petrol depot had painted 'A fair wind and an easy voyage' on the fuselage in Chinese characters, I let the seaplane drift fast across the river, and took off with the greatest ease. I had 48 gallons on board, and regretted not having filled right up with 60 gallons that I could certainly have lifted.

At first I could not pick out the Shell building from the great row all so much alike. Then I spotted the semaphore tower like a tall pillar on the riverside, and worked along from there. There seemed to be flags on every building for miles. Then I spotted three flags in a triangle â three flags after taking off so easily with a full load. I was disgusted at everything. I flew on up-river and easily located the company's hangar where it was kid's stuff taxiing up to a proper cradle with an expert crew and then drawing the seaplane up the smooth concrete. The Americans had a telephone into the city and I spoke to Paddy. I told him what I thought of his stopping me. He said, 'Quite impossible, my dear chap, quite impossible. Father Gherzi said there was a sixty to 70-mile wind against you. Sheer suicide.' I took the opportunity, with the seaplane on firm land, of inspecting the fuselage closely. The fabric was peeling off the underside of the fuselage, and the exposed plywood looked sodden. That glued plywood gave the seaplane its strength. If the glue had its life taken out by the sea water, the tail would break off in a gust. The

Gipsy Moth

was not built as a seaplane, and it was not built to stand up to sea water. As I ripped off the useless fabric and covered the three-ply with black bituminous paint I wished I had a parachute.

Gipsy Moth

was not built as a seaplane, and it was not built to stand up to sea water. As I ripped off the useless fabric and covered the three-ply with black bituminous paint I wished I had a parachute.

Other books

Jeanne Dugas of Acadia by Cassie Deveaux Cohoon

Alexandra Singer by Tea at the Grand Tazi

The Seducer (Viking Warriors) by Carlo, Jianne

The Mating Project by Sam Crescent

In the Garden of Deceit (Book 4) by Cynthia Wicklund

The Counterfeit Heiress by Tasha Alexander

Interrupted (The Progress Series) by Queau, Amy

One More Kiss by Mary Blayney

House Divided by Ben Ames Williams

Night and Day (Book 3): Bandit's Moon by White, Ken