The Lonely Sea and the Sky (45 page)

Read The Lonely Sea and the Sky Online

Authors: Sir Francis Chichester

What I regarded as a miraculous chain of events had started in London when I felt the urge to go to the South of France. There I reached a doctor who had been considered one of the cleverest lung physicians in Paris before he settled in Vence; also I had fetched up in a town which had been considered a health resort, with a magic quality of air for lungs, since the time of the Romans. How did this thing come about? Sheila said that the doctor gave me back my confidence, that my illness was already on its last legs. For myself, I think that some part of my body had ceased to function, that the doctor correctly diagnosed what this was, and supplied the deficiency. To me he was a wonderful man; short, nuggety, fit, with terrific energy exuding strength and activity. He never seemed to stop work, seeing thirty patients a day at times. I heard tales of his sitting up all night with a seriously ill patient, for two nights' running.

It was April when I fell into the good doctor's hands. In June I accepted an offer to navigate

Pym

in the Cowes-Dinard race.

Pym

was a fast, racing eleven-tonner, a beauty to sail, designed by Robert Clark and excellently sailed by Derek Boyer, her owner. I was not supposed to do anything but navigate, but I forgot, and hauled on a rope which caused a commotion in my lung. I coughed, spluttered and gasped, and finally had to call in a local French doctor at St. Malo to ginger me up. Derek said afterwards that he was worried stiff about me, but I was not worried about myself. By July I accepted an offer to navigate the crack Italian yacht

Mait II

in the Cowes Week Races, and in the Fastnet. This was great fun, with eleven Italians (seven of them Olympic helmsmen); none of them could speak English, and I could not speak any Italian. We talked in slow French. At the end of this Fastnet race, as we turned the Lizard into Plymouth Bay on the last lap, the wind piped up to a near gale. The wind was on our starboard quarter, and we were running fast towards the lee shore. It was murky weather, and the visibility poor; at the cliffs for which we were headed it might be very poor. I pondered the situation. If I were 400 yards out in my navigation, we could come slap up against the rocks at the entrance to Plymouth Sound. This would require turning instantly, and coming up into wind. I thought of the Council of War that had been held every time that I had previously suggested fresh tactics. I also thought, perhaps basely, that we had not done well enough in this race for five minutes extra sailing to entail the loss of it. I said, 'Alter course 10 degrees to starboard. We will make a landfall of the Eddystone Light before entering Plymouth Sound.'

Pym

in the Cowes-Dinard race.

Pym

was a fast, racing eleven-tonner, a beauty to sail, designed by Robert Clark and excellently sailed by Derek Boyer, her owner. I was not supposed to do anything but navigate, but I forgot, and hauled on a rope which caused a commotion in my lung. I coughed, spluttered and gasped, and finally had to call in a local French doctor at St. Malo to ginger me up. Derek said afterwards that he was worried stiff about me, but I was not worried about myself. By July I accepted an offer to navigate the crack Italian yacht

Mait II

in the Cowes Week Races, and in the Fastnet. This was great fun, with eleven Italians (seven of them Olympic helmsmen); none of them could speak English, and I could not speak any Italian. We talked in slow French. At the end of this Fastnet race, as we turned the Lizard into Plymouth Bay on the last lap, the wind piped up to a near gale. The wind was on our starboard quarter, and we were running fast towards the lee shore. It was murky weather, and the visibility poor; at the cliffs for which we were headed it might be very poor. I pondered the situation. If I were 400 yards out in my navigation, we could come slap up against the rocks at the entrance to Plymouth Sound. This would require turning instantly, and coming up into wind. I thought of the Council of War that had been held every time that I had previously suggested fresh tactics. I also thought, perhaps basely, that we had not done well enough in this race for five minutes extra sailing to entail the loss of it. I said, 'Alter course 10 degrees to starboard. We will make a landfall of the Eddystone Light before entering Plymouth Sound.'

My great friend Michael Richey was navigating the Swedish yacht

Anitra

. They had come along earlier in similar conditions, but with the visibility worse. Mike said to the owner, 'If my navigation is correct, we shall make Plymouth breakwater (the finishing line) and win the race, but if it isn't we shall pile up on the rocks outside. It's your yacht, you decide.' Sven Hanson the owner, said, 'Carry on.' And so

Anitra

won the Fastnet race of 1959.

Anitra

. They had come along earlier in similar conditions, but with the visibility worse. Mike said to the owner, 'If my navigation is correct, we shall make Plymouth breakwater (the finishing line) and win the race, but if it isn't we shall pile up on the rocks outside. It's your yacht, you decide.' Sven Hanson the owner, said, 'Carry on.' And so

Anitra

won the Fastnet race of 1959.

People criticised Sheila for letting me go ocean racing; they thought that I was still too ill because I coughed a lot, and had periodic attacks of bronchitis, asthma and other things. But Sheila staunchly stood up for her opinion that it was the best thing for me. She has a strange and amazing flair for health and healing. She believes most strongly in the power of prayer. When I was at my worst, she rallied many people to pray for me, my friends and others. Whether Protestants, Roman Catholics or Christian Scientists, she rallied them indefatigably to prayer. I feel shy about my troubles being imposed on others, but the power of prayer is miraculous. Hardly anyone would doubt its power for evil â for example the way the Australian aborigines can will a member of their tribe to death; so why should its power for good be doubted? On the material side I believe that fasting is the strongest medicine available and that it played a very important part in my recovery. I believe that my being a vegetarian for preference helped a lot.

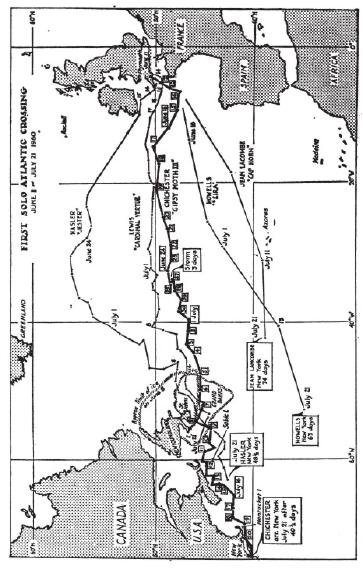

After the Fastnet race, when I entered the Royal Ocean Racing Club again, I spotted Blondie Hasler's notice about the proposed solo Atlantic race, still on the board. I thought, 'Good God! I believe I can go in for this race.' I regard it as miraculous that within thirty-two months of first being taken ill, and within fifteen months of my appealing to Dr. Mattei for oxygen in Vence, I was able to cross the starting line for the toughest yacht race that has ever taken place, and able to finish it in forty and a half days. However, during the next eight months, it was touch and go whether the race would ever get organised, and touch and go whether the yacht and I could get to the starting line. It was formidable; the prospect of racing alone across the Atlantic, when I had never been alone in any boat larger than a 12-foot dinghy.

PART 5

CHAPTER 27

TRANSATLANTIC SOLO

A solo race across the Atlantic from east to west was the greatest yacht race that I had ever heard of, and it fired my imagination. Three thousand miles, plugging into the prevailing westerlies, probably strong, bucking the Gulf Stream current, crossing the Grand Banks off Newfoundland which were not only one of the densest fog areas of the world, but also stuffed with fishing trawlers. No wonder the Atlantic had only once before been raced across from east to west. That was in 1870, by two big schooners, the

Dauntless

and the

Cambria

. The

Dauntless

, 124-foot long with a crew of thirty-nine, and a potential speed of 14 knots, lost the race by one hour and thirty-seven minutes, due, it was said, to spending two hours looking for two of her crew washed overboard while changing a jib. Anything once lost sight of in a seaway is difficult to find again, so 'it is not surprising that they failed to recover the men overboard.

Dauntless

and the

Cambria

. The

Dauntless

, 124-foot long with a crew of thirty-nine, and a potential speed of 14 knots, lost the race by one hour and thirty-seven minutes, due, it was said, to spending two hours looking for two of her crew washed overboard while changing a jib. Anything once lost sight of in a seaway is difficult to find again, so 'it is not surprising that they failed to recover the men overboard.

Sheila backed me in every way to get into this race. She was criticised for this because I was thought to be still a sick man, but she stuck to her view that it would complete my cure. I wrote to Colonel Hasler and disputed some of his proposed conditions for the race, particularly one that entrants must first qualify by a solo sail to the Fastnet Rock and back. This course requires constant accurate navigation throughout, because of the nearness of land and the shipping routes along it, and a single-hander would find it difficult to get any sleep during the six to ten days' sail. Blondie Hasler came to my office for a talk. He was a quiet-speaking, interesting man; short, round and bald-headed with a red face. He never seemed to move a muscle while speaking. He steadily and quietly pursued his affairs. He was a regular officer of the Marines, retired with a total disability pension for a back injury, and famous for the expedition he thought up and led in the war which resulted in his being known as the Cockleshell Hero. Ten Marines in canoes made their way 60 miles up the Gironde River to Bordeaux, where they sank several steamers at the quayside. Only two of them returned alive. Blondie was also an expert ocean racer, and one year, with a novel type of boat for ocean racing, came top of the smallest class of the RORC for the season's racing.

Blondie's proposal was that this Atlantic solo race would encourage the development of suitable boats, gear and technique to simplify sailing. But the race had stuck; people were scared of it, saying that it was a dangerous hair-brained scheme. Sheila and I threw all our weight into the effort to get it going again. Blondie had first suggested the race to the Slocum Society of America, who seemed to me an amiable bunch of cranky American sailors quite different from what one would expect to find associated with the name of Slocum, who was an expert navigator as well as a fine sailor and a fine man. The Slocum Society had first praised the idea of such a race, later refused to support it, and now seemed to have lost all interest in it. Blondie had also enlisted the interest of the editor of

The Observer

, David Astor, a friend of his who had served with him in the Marines. It seemed at first that a starting line was the only thing needed for a race across the Atlantic, but the hard truth was that it also needed considerable money for a yacht in racing trim, with the special gear and six months' stores required for a double crossing of the Atlantic, apart from expenses while in America. During that half year a man would be away from his job, and probably receiving no income from it. At first

The Observer

offered a prize of £1,000 for the winner, and £250 for each yacht taking part. Then they shrank into their shell, warned that if the yachts were sunk, their rivals would tear them in pieces for luring the flower of young British manhood to its doom with offers of sordid gold. Fortunately they were a sporting lot, with Chris Brasher and Lindley Abbatt backing up the Editor, and finally they offered £250 each to any starter as option money for the winner's story, for which another £750 would be paid. Several good clubs were asked to start this race, but all turned it down. One of my friends, Bill Waleran, suggested the Royal Western Yacht Club of England. Of course! Plymouth was the traditional place from which to set sail for America, and the RWYC was the club to take over the race â it had sponsored the first Fastnet Race, and the RORC had been founded in its club rooms. The Slocum Society agreed to finish the race.

The Observer

, David Astor, a friend of his who had served with him in the Marines. It seemed at first that a starting line was the only thing needed for a race across the Atlantic, but the hard truth was that it also needed considerable money for a yacht in racing trim, with the special gear and six months' stores required for a double crossing of the Atlantic, apart from expenses while in America. During that half year a man would be away from his job, and probably receiving no income from it. At first

The Observer

offered a prize of £1,000 for the winner, and £250 for each yacht taking part. Then they shrank into their shell, warned that if the yachts were sunk, their rivals would tear them in pieces for luring the flower of young British manhood to its doom with offers of sordid gold. Fortunately they were a sporting lot, with Chris Brasher and Lindley Abbatt backing up the Editor, and finally they offered £250 each to any starter as option money for the winner's story, for which another £750 would be paid. Several good clubs were asked to start this race, but all turned it down. One of my friends, Bill Waleran, suggested the Royal Western Yacht Club of England. Of course! Plymouth was the traditional place from which to set sail for America, and the RWYC was the club to take over the race â it had sponsored the first Fastnet Race, and the RORC had been founded in its club rooms. The Slocum Society agreed to finish the race.

The prize money may seem small compared with some of the prizes in horse races and other matches, but we were concerned only to be able to take part in such a race. At one stage, when it looked as if no one would sponsor, start or finish the race, I offered to race Blondie across for half a crown.

Blondie's entry for the race was a junk-rigged folkboat. It has been said that the junk sail is the most efficient in existence, and certainly the Chinese have had thousands of years in which to perfect it. Joshua Slocum, that great sailor and the first man to sail around the world alone, built himself a junk-rigged canoe in the 1890s, and sailed in it with his family from Buenos Aires to New England, making a fast passage, including one day's run of 150 miles. Blondie was a canny, tough seadog, and with his yacht made a formidable rival.

I was going to race my new yacht

Gipsy Moth III

which had been launched the previous September. She had been built during my illness, and few new yachts can have been less supervised or visited by the owner. We saw her only twice while she was building. Once during a temporary improvement in my lung trouble I flew over to Dublin with Robert Clark and Sheila. While Robert and I walked down to the yard beside the river, the biting cold wind seemed to drive right through me. Robert grew more and more irritated at my stops for coughing bouts, and finally snapped, 'Stop coughing, now!' To my astonishment I did stop, and wondered if I must be a

malade imaginaire

. Fortunately for Robert this lull did not last long, otherwise I should have had to ask him to live with me until his new cure was complete.

Gipsy Moth III

which had been launched the previous September. She had been built during my illness, and few new yachts can have been less supervised or visited by the owner. We saw her only twice while she was building. Once during a temporary improvement in my lung trouble I flew over to Dublin with Robert Clark and Sheila. While Robert and I walked down to the yard beside the river, the biting cold wind seemed to drive right through me. Robert grew more and more irritated at my stops for coughing bouts, and finally snapped, 'Stop coughing, now!' To my astonishment I did stop, and wondered if I must be a

malade imaginaire

. Fortunately for Robert this lull did not last long, otherwise I should have had to ask him to live with me until his new cure was complete.

When we visited the yacht, Sheila said that the seats in the main cabin were too low. Robert assured her that they were the standard height. Sheila, probably because she is a portrait painter, has an incredible eye for line and form. She was convinced that they were too low, and refused to budge in her opinion. They argued about it for hours on the way back to the hotel and throughout the evening, but Sheila, although she was opposing a famous architect who had been designing yachts all his life, refused to change her view. Before breakfast next morning Robert went down to the yacht and returned with this story: the water tanks under the cabin sole (floor) had been built the wrong shape, and were two inches higher than designed. Instead of re-making the tanks the yard had re-made the cabin sole two inches higher.

Several times when my illness was at its worst and seemed hopeless, I said, 'Sell the yacht, and let's be free of that worry at least.' Each time, however, I changed my mind and hung on. Jack Tyrrell and his firm were very good about my illness; they moved the half built yacht to the side of the shed, and let it rest there until I was well enough to consider starting again. In September 1259, after the Fastnet Race in

Mait II

, Sheila and I crossed to Arklow on a Monday morning to launch the yacht, which we found sitting in her cradle beside the river. The tides are erratic there, and we waited about all Tuesday for enough water to launch her. We had given up hope for the day, and were in the middle of our dinner at the hotel, when a boy came rushing up to say that the boat would be launched in ten minutes. We dropped our forks, grabbed a bottle of champagne, and rushed down to the yard. There were only a few people standing by when Sheila climbed on to the platform and well and truly crashed the champagne on the stem of the yacht, showering us with champagne and glass fragments as she named the yacht

Gipsy Moth III

. The yacht had looked powerful and tall standing on the hard of the river bank, and slid away quietly into the water.

Mait II

, Sheila and I crossed to Arklow on a Monday morning to launch the yacht, which we found sitting in her cradle beside the river. The tides are erratic there, and we waited about all Tuesday for enough water to launch her. We had given up hope for the day, and were in the middle of our dinner at the hotel, when a boy came rushing up to say that the boat would be launched in ten minutes. We dropped our forks, grabbed a bottle of champagne, and rushed down to the yard. There were only a few people standing by when Sheila climbed on to the platform and well and truly crashed the champagne on the stem of the yacht, showering us with champagne and glass fragments as she named the yacht

Gipsy Moth III

. The yacht had looked powerful and tall standing on the hard of the river bank, and slid away quietly into the water.

Other books

Escape From Home by Avi

Michael Vey 3 ~ Battle of the Ampere by Richard Paul Evans

Three Continents by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

4 A Plague of Angels: A Sir Robert Carey Mystery by P. F. Chisholm

Wildflowers by Fleet Suki

Ships and Stings and Wedding Rings by Jodi Taylor

Up the Down Volcano (Kindle Single) by Crosley, Sloane

Daughter of Regals by Stephen R. Donaldson

A Man of Honor by Ethan Radcliff

Prickly By Nature by Piper Vaughn and Kenzie Cade