The Longest Fight (11 page)

Authors: Emily Bullock

Pearl was the only thing he hadn’t ruined in his life, and even that wasn’t quite true. She came out of that night at Albany Basin all wrong: no feeling of pain, no cries to warn them when the food was scalding or the shoes too tight, just the web of scars and bruises on her numb skin. Watching her sleeping, he couldn’t help wondering if it all could have been different. It was easier to imagine the way things should have

been when she was still and quiet. But Georgie was right, she wasn’t a kid any more, and now there was Frank to look out for too. Frank was down in the kitchen – the soft padding footsteps. It was a relief to hear something other than the sound of Pearl breathing. All those years she had been on the other side of the wall, that snuffling breath all he heard until he thought he might go mad from it, wanted to hold the pillow down on her round face just to get some peace.

Jack pressed his hands to his ears but it only made the sound louder and he let his arms drop.

The forces at work.

Jack heard his mum’s voice of disapproval trapped in the grainy surface of the floorboards. The forces his mum always complained of, the things that made people do bad things. The forces that finally took her away: fear of falling under a bus, fear of leaving the house, fear of eating bad food, until there was nothing left to do but curl up and die. Fuck that; Jack could fight them all. But some nights, when he was younger, he used to wake up, shivering-cold, worried that he would do something to Pearl, hurt her somehow. A bit of his dad left on him like a sweat stain. Then there were other times, stranger times, when Jack saw her, when they weren’t squabbling or rubbing each other up the wrong way, and he knew he’d rather suffer anything, rather die than see her cry. What was that? It didn’t matter if he was a

fucking waste of Munday blood;

he had heard that all before. He was there to make sure Pearl made it through to the very end. Jack crossed the hall to his room and lay down fully clothed on the covers. Arms and legs spread wide, knocked out for the count.

‘Roughly described, “personal error” is the time which elapses between the mind deciding on an action and the body getting to work to execute it.’

Boxing,

A.J. Newton

A

new arse on the throne for well over two months now and another two wins for Frank; Jack felt stupid even thinking it but things did seem different. A brighter tint to the sun outside; people let their smiles linger a little longer. He shifted on the stool at the bar. Only just after six-thirty; most fools hadn’t found their way in yet, just Jack and a couple of old timers in the pub nursing bottles of stout. Georgie was due in soon; Jack ordered his first drink of the day as he waited for her. Over breakfast he had decided that she was going to be his lucky rabbit’s foot for the night. It was time to do more business, and he had some promoters coming to Manor Place Baths off the Walworth Road. The Thin Suit’s boss would be there. Jack knew there was nothing to worry about, but he didn’t want to tempt fate. The first hit of beer soothed his mouth. Still, he couldn’t shift the congealing taste of worry that lodged in his throat.

Newton sat down next to him. ‘Seems like it might be a nice one this evening. Don’t you think, Jack?’

Jack took another swig.

‘Got any plans? My wife made me get one of those television sets for the big occasion. Thought we might keep it. Come over if you want, bring Pearl. My Jimmy was outside the Abbey – they filmed him at the celebrations, you know? My boy inside that box. Ain’t that funny, Jack, about Jimmy?’

Jack lit a cigarette. Newton might have lost a leg before the war but he talked so much that sometimes Jack would have willingly given him his own leg just to get away. That tin peg of his didn’t even creak enough to act as a warning signal,

and now Jack was stuck with him until Georgie arrived. He scanned the room for somewhere else to take his pint, but in the end he didn’t even need to move from his seat. Jack reached behind the bar and scooped up a copy of the

Daily Express.

Christie’s face plastered across the front page again, his dark eyes peering out into the pub – a face to make a child cry. Jack read the pages and ignored the ramblings of Newton. But bits of Newton’s life filtered down into Jack’s head and he lost his place on the page. Jimmy doing well now he was a fully signed-up member of the cloth; Jimmy doing the Lord’s work with all those sinners up at Pentonville; Jimmy thinking of buying a car; Jimmy looking to move up in the church ranks. Newton did a good job of selling his chaplain son. If the tarts in the paper had had such a good salesman behind them, maybe they wouldn’t have ended up in Christie’s downstairs pantry. Jack licked his finger, turned the page.

The newspaper called them

young ladies

but everyone knew what they were. Jack didn’t have a problem with them: worse ways to earn a living, like down the docks or at the meat market, chained up in a factory. Jack didn’t know how Pearl stood it every day at that pastille place, coming home reeking of blackcurrant, but he supposed she had nothing better to do. Jack pitied people who didn’t have plans. All Newton did was drink and spout rubbish about his blessed son. He pointed over Jack’s shoulder at the picture of Christie.

‘Jimmy hears some stories up at the prison. The war damaged a lot of those men.’

‘Maybe it did. But we don’t all go around strangling women, much as some might deserve it.’

Jack gave up on the newspaper, left it open on the bar. But he wanted to ask Newton if the rumours were true, if Christie really did those things to the women when they were lying warm but dead, the things they wouldn’t report in the paper. Newton’s son must know; he worked at the prison, after all. Jack felt the weight of change in his pocket, enough for another pint for himself and one for Newton. If he just topped

Newton up with another drink the information would come flowing out. That would be a tale to tell down the gym.

But it was something his dad always did: offering up treats when he wanted something, throwing out punches when it suited him, and driving apart his family until each stayed in their own corner of the ring. Jack let the coins slip between his fingers. Newton could buy his own drink, and his son could go to hell. Jack, son of John: two separate lines on the census that never had to meet again. He flicked ash to the floor. The old timers rambled on. One of the men raised his glass at Jack.

‘What regiment were you in, son?’

They were talking about the war again, and Jack didn’t know what people had ever had to speak about before Germany had set its sights on running the world.

‘I did my bit.’

Newton wiped the beer from his lips. ‘Your brothers were with the East Surrey lot. But you were in the ARP, weren’t you, Jack?’

‘A fit young man like you should have been off fighting somewhere.’ The bloke next to Newton wrinkled his face up into a frown. They couldn’t have been much more than forty years old but Jack did look like a young man next to them. Their faces were bleached as the paving slabs outside the pub and just as cracked.

‘Well, I weren’t. I were here, saving your home from burning to the ground.’ Jack took another mouthful of beer.

‘Still…’ Newton’s voice trailed away.

Always that doubt hanging in the air. He’d been nineteen when he’d signed up; the war was meant to be his way out of it all. Collapsed arches, the medical slip said. Jack had hoped they wouldn’t notice like the trainers down at the gym hadn’t, but one doctor with a vicious streak wide as London Bridge got him discharged on to civilian duties. Jack got stuck in the ARP along with the schoolboys and grandads. Hanging round the bases organising fights wasn’t enough to earn respect, and

sometimes Jack would wait hours at his post so he could leave after blackout. With the collar of his coat turned up and the helmet under his arm he could almost pass for wearing a uniform as he slipped through the dark streets.

‘Been waiting long for me?’ Georgie held on to the pump; he hadn’t noticed her come in. ‘What can I get you, Jack?’

More questions, always questions. The men gave him sly glances, nodding at each other. He pushed his empty pint away.

‘This one’s dead. I’m done with it.’

‘Suit yourself.’

Georgie’s mouth shut tight as she snatched the glass away; she would sink into a sour sulk if he wasn’t careful. Her eye-teeth had a sharp little way of cutting into her bottom lip when a mood came on her, and he’d seen her snarl at men on the other side of the counter. Jack didn’t want her ruining his luck for the night. He followed her down to the other end of the bar, reaching across to take her arm.

‘It’s a big night for me. Got to be ready to duck and weave. In my head I’m already there, if you know what I mean. But I did want to see you.’

‘A punchbag you want, is it? Well, I ain’t swinging your way.’

‘Not even this Friday? Come up the house. Pearl’s doing pie and mash.’

Jack touched the cuff of her blouse; his fingers slipped inside and rubbed the small round bone on her wrist.

‘All right, then, I’ll get off early, Jack. But I like gravy not liquor on my pie.’

He held on to her sleeve, a white cotton blouse with silver buttons worn to a silky finish with age, and beneath it Jack almost thought he could see the rippling of her skin. He wanted to breathe her in.

‘Better get off now before you lose some of that edge.’ She slowly untangled herself, heading to the pumps. A ladder threaded its way up her left stocking and he wanted

to put his finger inside to feel her warm skin. Stockings were safe, something he never saw before the war, something that wouldn’t spark to life the memories of before: summer evenings lying under the trees on the Common, Rosie’s white socks and lace-up boots threaded between his legs. Jack followed the line of Georgie’s stockings up to the hem of her dark green skirt. He tried to concentrate, imagining her thighs spilling over the tight string garters. He felt a tingling at the tip of his fingers just as if he had been stroking a rabbit’s foot; but he couldn’t hold Georgie, couldn’t drag her out from behind the bar. The sweat was building up beneath the wool of his suit, nipping at his skin. He liked to do business that way, the thing he wanted just out of reach, and it made him run faster than a dog at the track.

Manor Place Baths felt as if it was on fire, and Jack had stood near some giant blazes in his time. The exposed bricks of the walls and the wooden floors pumped out more heat than they ever did on washday when the coppers boiled and spewed. Bert was there already. Jack leaned against the pillar beside him. ‘How you doing?’

Bert nodded in reply, small and round as a ball, securely tucked into a starched shirt. Rolls of fat threatened to spill over his trousers, and Jack could count the wisps of hair on his head. Even his glasses were little circles of silver metal, but there was nothing soft about him.

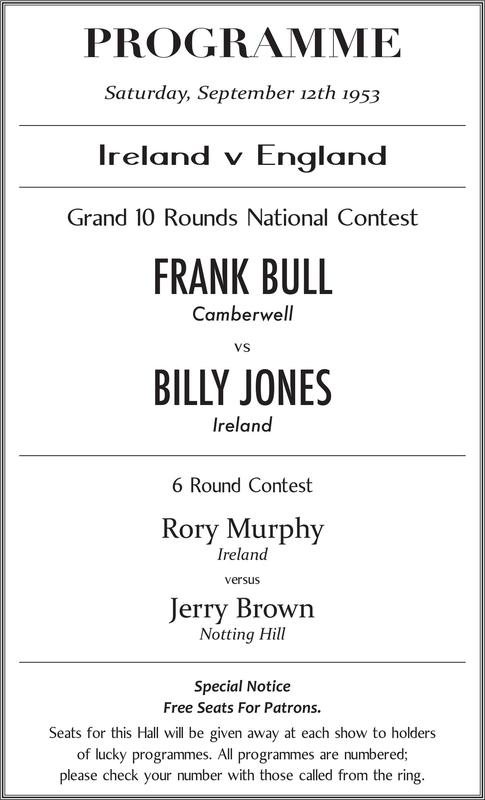

‘Full programme tonight – doubt there’ll be any surprises. I’ve warned Frank to take it easy. We’ve got a proper fight next week.’ Bert folded his arms, one on top of the other.

‘My boy needs to be seen by the right people.’

Jack strained his neck, trying to spot other faces in the crowd. The bell for the first fight sounded. He stood up straight as the crowd began to push around him. The names were called out: Big Roberts from out west in the left corner, and someone or other over in the right. Bert rocked on his

heels to get a better view of the ring. Jack turned away, tilting his head back to take in the baths. The Thin Suit was easy to spot in the mass of Burton’s tailoring – the same long legs and arms but the cloth looked different, a chocolatey brown this time: made to measure. A big bulk of a man walked behind, the Thin Suit sweeping people aside. Jack wanted to know what it felt like to lead your life at the head of the procession. He nudged Bert. ‘Hope they’re coming our way.’

‘Be careful what you wish for. I’ve got to see a man about a dog.’ Bert ducked his head and was gone.

Jack willed them closer: step to the left; don’t talk to that bloke, he’s nobody; keep coming; this way. The Thin Suit stopped, indicated the man next to him. ‘Jack, this is Mr Metzger. He takes a great interest in new fighters.’

Jack wanted to stamp his feet and tell the world he was right – they had come for him. Heads turned: Jack had arrived.

‘Only the taxman calls me Mr Metzger. The name’s Vincent.’ He didn’t try to raise his voice above the thud of fists and whistles from the crowd.

‘Good to meet you. So you’ve heard about my new signing?’ Jack held out his hand.

Vincent gripped it with a firmness that didn’t match his velvet voice. Gold watch, cufflinks, and two rings; Jack had never seen so much metal even in the pawnshop window. It gave Vincent’s skin a yellow tinge; with the black suit and black hair, it made him look like a wasp. But somehow, staring into those green eyes, Jack didn’t find the picture funny.

Vincent lit a cigar.

‘My Frank’s the best you’ll see here tonight, best you’ll see anywhere –’

‘Slow down, boy. We don’t talk business in public. But I do need a drink.’

A cloud of dusty smoke filled Jack’s nostrils, dry as burning leaves; he tasted money. He looked at the Thin Suit, wanted to tell him to hold the ice, but he didn’t seem the type to take backchat. The Thin Suit clenched and released

something in his outside pocket; it made the muscles on one side of his neck tremble like piano wires.

‘Get yourself one too, Jack. I never trust a man that don’t drink.’ Vincent patted his arm.

He wasn’t anyone’s skivvy but a drink would hit the spot. It was probably one of those test things. Vincent wanted to see what drink he came back with. Jack nodded and walked off. The hall was thick with smoke and the scent of whisky slipping off the cracked white tiles. Jack knew most of the men in there hadn’t suffered under rationing, he could see it in the strain of their seams and the brightness of their skin. But those blokes were old, their turn nearly up. Jack lit a cigarette. Even in his cheap suit he was better turned-out than those overfed lumps. The other promoters were easy to spot: people moved around them thick as flies, but they kept to their own corners. Hands waving, arms locked, shifting footwork. Let them step out of his way. No one noticed the knocked elbows and spilt drinks; they had other fights going on. Jack was sharp as the clink of glasses and the scratch of fountain pens.

The tray of drinks sat in front of him: bottles of dark beers, sediment settled in the bottom, a clear liquid perfumed like gin. Off to his left the bell for the next fight went. Frank stood in the blue shorts, Champagne in the red. It wasn’t a real match, just a bit of display: some good technique, swift footing. Champagne kept to his role as journeyman – moving Frank around, showing his best side. The seats in front of the low ring were taken, ice cubes melting from the heat off the fighters, the sweetness of booze replaced by liniment and sweat. Spider stepped up to the table, pressing his palms down beside the bottles; his shadow seeped into the wall.

‘Evening, Jack. Frank’s doing good. Bet you’re glad I let you sign him up.’

‘Don’t even think about lifting any wallets here.’ Jack blew smoke into the space between them.

Spider waved his hand. ‘Nah, I’m not into that no more. That Vincent Metzger you were talking to?’

He scratched a fingernail along the deepest scar on his cheek.

‘Course it was.’

Spider stuck out his chin and nodded. ‘What you talking about?’

‘That’s man business, son.’

‘You’re a funny bloke, Jack. But I seem to recall I did you a favour by letting you take Frank on. How about paying me back?’

Jack handed a bottle of beer to Spider. ‘Take this, son. Now walk away before it all ends in tears.’ Some day someone would teach the boy a lesson, but Jack didn’t have time to get distracted tonight. He picked up two glasses of whisky from the tray and carried them back to Vincent. He wanted to feel the golden liquid, smooth as Milandu toffees, slip down his throat. He stubbed out the cigarette on a pillar as he passed, stretched the cuffs of his shirt.

‘Here you go.’

‘Bottoms up.’ Vincent sipped his drink. ‘Good choice.’

Another suit had appeared next to Vincent, and they were staring at Jack like a couple of magpies: one for sorrow, two for joy. Vincent waved at the suit with his hand.