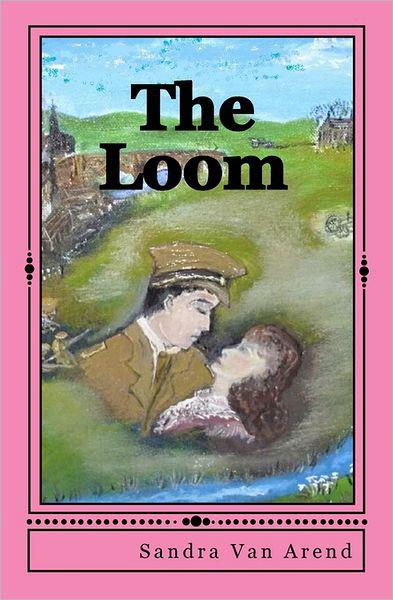

The Loom

Authors: Sandra van Arend

| The Loom |

| Sandra van Arend |

| CreateSpace (2011) |

THE LOOM This story is fiction, but like most fiction is based on fact. It is the story of Leah Hammond and her life in England in the early nineteen hundreds. Leah is born in Lancashire and begins her early life as a mill worker at the age of twelve. In essence, however, the story is a romantic saga, but also of the very real life dramas of Leah as a child, then adolescent and finally young woman; and how she tries to escape the confines of the narrow, regulated and often poverty stricken life into which she is born. The era in which this story takes place is an increasingly turbulent one, encompassing World War One, social reforms; the rise of radical movements, the emancipation of women; and how Leah copes with this world of change and the trials and tribulations of a woman of these times.

Sandra van Arend was born in Great Harwood, Lancashire. She migrated from England to Australia at the age of ten and was educated in Adelaide. She has spent much of her life as a teacher and completed her Masters Degree in Creative Writing in 2000. She has since written four novels and a biography. The Loom is her first novel.

The Loom

The LOOM

SANDRA VAN AREND

Copyright © 2011 Sandra van Arend

All rights reserved.

ISBN:

ISBN-13:

978-1461175193

LCCN:

In loving memory of my mother

Maria Burrow

These stories are her stories

Many thanks to my brother-in-law

Hans van Arend

Who helped to get this book launched.

PROLOGUE

L

eah had only a vague recollection of her father in those days: an often absent figure, big to her smallness and very dark (although Harold was, in fact, of medium height and quite slim). Post separation Leah’s knowledge of her father was second-hand, through her mother mainly, although she would sometimes catch glimpses of him in the small town where they lived.

Leah was a little afraid of her father, although he’d kept his distance, quite possibly because Emma had told him to. When she was older Leah noticed that he was always nattily dressed, back as straight as a ramrod, even in drink. She avoided him where she could, although Harold had never been violent.

Leah was wary of men when she was young, (and even as an adult), most probably because she had very little to do with them, and thankfully Emma never had another relationship with a man. One’s enough, Emma would say, with feeling.

From her mother Leah had formed a sketchy picture of Harold: her father was a drunkard, he was handsome when young and that, to Leah, (always conscious of a good appearance), was a bit of a consolation.

Unfortunately, Harold was run over in middle age by the one and only car in the small northern town of Harwood, where they lived. When they were told the news Emma was sad, but she was definitely not prostrated with grief and although she hadn’t wished him dead, his death did not affect her a great deal. She did, however, comment that he’d never had much luck, although only Emma knew all the details.

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

H

arold was drunk again! Nothing unusual! He stumped around in the scullery, banging into things. A drawer was pulled open, viciously. The cutlery in it, what little they had, rattled noisily. The drawer was warped, and she could hear him trying vainly to get it back in, muttering and cursing. He stumbled around.

‘Damn and blast.’

He was worse tonight! You put up with it she’d been told, time and time again, like most of the women in Harwood, whose men were boozers. Men who worked long hours in the mines, coming home parched and weary from stints in those subterranean caverns, covered in coal dust, lungs rotting from it, to slake their thirst in the nearest pub.

Who could blame them?

Emma Hammond did! She would have been willing to accept it, though. What she couldn’t accept was Harold’s womanising! Drink, yes, another woman, definitely no! She’d had enough!

On this particular night she’d sent Darkie, Leah and Janey to bed early, all of them complaining they weren’t tired, they wanted to play, to read, anything but put on their nightwear and get into bed. She’d almost had to take the strap to them, although she wasn’t one to normally do that. They didn’t know it but they would be woken at first light, even before the knocker up man appeared on the scene.

She’d decided that morning!

So when Harold put his head round the scullery door and slurred, ‘where’s me dinner, Emma,’ he was vaguely surprised, through the fog of drink, when she replied amiably,

‘I’ll get it for you, Harold. Just hold on a tick, will you.’

Emma closed the door quietly behind her.

‘Pick up that parcel, lad,’

she said to Darkie, her eldest child of seven, black hair and coal black eyes like his father, but tall, like her. Leah, four and Janey, two, stood next to him, in coat, bonnet and mittens, which she knew they’d need as it was bitterly cold. Emma had a twinge of conscience as she looked at them as they stood forlornly next to her on the pavement. Poor little sods, Emma thought, as she picked up the other brown paper parcel, but she knew that she couldn’t stand it with Harold another minute.

‘I’m cold, Mam,’ Leah said, shivering.

‘Sh…sh… We don’t want to wake your Dad. You’ll be all right in a minute. We’ll walk quick, that’ll get us warm. Come on now or we’ll miss the train to Accrington.’

Dawn was an eerie morning light, the mist beginning to lift, whorls of ghostly gray hanging spectre-like, wavering and curling like some macabre dancer. The knocker up man had just begun to extinguish the light in the gas lamps.

‘It’s no good carrying on like that, Emma. What’s done’s done. You know I always said you shouldn’t have married him, now, didn’t I?’ Dora Winfield gazed at her daughter, a look of sympathy on her face, tinged with exasperation.

‘If you say that once more, Mam, I’ll scream, I will that.’

Emma Hammond’s expressive face was a picture of misery. Her mother sat stolidly on her chair with her usual pint pot of hot, strong tea in her hand. She needed that tea at the moment as she thought of her daughter, of her three grandchildren and that sod of a son-in-law of hers.

They’d only just settled the children upstairs after a round of moaning and crying. There hadn’t been a muff for at least ten minutes so hopefully, they were asleep. She was just about at the end of her tether with the whole lot!

‘I know I’ve said it before, lass, but it’s true and it’s no good going around with your face like a poker. That’ll do no one any good, least of all the children. They don’t know whether they’re coming or going, what with the way you’re carrying on and bloody Harold.’

‘I know, I know.’

Emma’s face began to twitch. Not again, Dora thought so she said hurriedly.

‘Now, now, don’t start. It’s been nearly three weeks since you left and it’s no good crying over spilt milk. Let’s just have another nice cup of tea, love and you’ll feel better.’

Tea was Dora’s remedy for everything! She heaved herself off the chair and put the kettle on to boil for what seemed like the tenth time that morning. Her mother drank gallons of tea and her insides must be black. It was good for dyeing hair, too, according to Dora – ‘me Mam combed her hair with tea every day of her life and she went to her grave with not a gray hair in her head’.

If she’d heard that once she’d heard it a thousand times, and what a consolation when you were dead! Emma had controlled herself by this time and watched her mother’s fat, comforting back looking as steady as the Rock of Gibraltar as she poured water into the teapot.

Dora set the pot of strong, sweet black tea in front of Emma. Then she deliberately placed her hands on the table and put her face close to Emma’s, an annoying habit she had, so that Emma could see up her nostril.. She looked away quickly.

‘You know what I’d do, our Emma?’

‘What?’ Emma was sure she’d heard it before but she’d humour her mother because she’d been good with them. She wouldn’t like to have three children and a crying daughter hoisted on her. She hadn’t wanted to do this to her mother, either. All she wanted was to be back at her own fireside toasting teacakes on a knife in front of the fire, or ironing, or even darning socks, which she hated. Anything would have been preferable to gallivanting around in the middle of the night with three children hanging on to you, moaning and whining that they were cold, they were hungry, they wanted to go home.

‘If it was up to me I’d get that bugger out of the house.’ Emma tuned in again. ‘He’s got a bloody cheek he has, letting you leave and him staying there, all nice and cosy like and he hasn’t even bothered to come over and see the children. Not that you’re not welcome here, mind, but it’s not right: him staying and you and the children having leave.’

Dora straightened up and sat down in the chair with a thump. There, she’d said her bit, now it was up to Emma.

Emma took a piece of calico from the sleeve of her blouse where she’d tucked it, and blew her nose.

Her eyes were red and there was a catch in her voice when she said.

‘That’s easier said than done. Now, you tell me how on earth I can get him out, short of shooting him, and I’d do that if I could get away with it, I would, the bloody swine.’

Emma’s face darkened as she thought of Harold and what he’d done to her. Taking up with that fow-faced Annie Mullen! She could kill him, she really could.

‘Sorry, what, Mam?’ Her mother was looking at her in annoyance.

‘Ee, it’s like talking to a stone wall sometimes.’ Dora said, exasperated.

‘I was just saying that I saw Mrs. Rishton from up your street. She’s visiting her sister who lives next door here. Do you know what she told me?’

‘What?’ Emma’s mind was not totally on her mother at the moment, but she sat up with a jerk at her mother’s next statement. As though she’d been given an electric shock or something, thought Dora. This might just be what she needed to get her off her bum, and stop that crying because that was all she’d done since the day she’d left. Cry! Or go upstairs to the bedroom, fling herself on the bed and cry up there, leaving her to look after the children, thank you very much!

‘Mrs. Rishton said that your Harold had given up his job in the pit and has been put on at the new Co-op site at the top of Glebe Street. You know, near the Square. And listen to this, he’s got four fellas living with him as well. So what do you think of that for cheek, eh?’

Indignation was written all over Dora’s face. Dora could have written a book with her expressions!

‘What?’ Emma was suddenly filled with rage. ‘He can’t do that, the cheeky sod.’

‘Well, he has, an’ all; and not only that. Mrs. Rishton said that there’d been a few drunken sprees in that house: sozzled up to the eyeballs, all of ‘em, from all accounts.’

Emma didn’t know how she got back to Harwood so fast. She hadn’t been able to wait for the bus she was so incensed at what she’d heard. So she walked, or had she flown, because it seemed no time that she was on the outskirts of Harwood, her mind in a whirl.

Before her lay the small town of Harwood, dingy terrace houses built on the slight incline of the dale, mill chimneys tall and grey, smoke stacks belching putrid black smoke. Emma didn’t notice any of this. All she could remember was that she’d been so mad she’d hadn’t been able to get out of her mother’s house fast enough, and Dora had followed her halfway down the street trying to dissuade her.