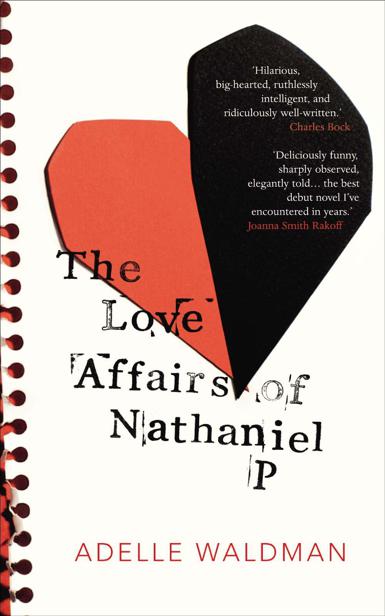

The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.

Read The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. Online

Authors: Adelle Waldman

Contents

Nathaniel Piven is a rising star in Brooklyn’s literary scene. After several lean, striving years and an early life as a class-A nerd, he now (to his surprise) has a lucrative book deal, his pick of plum magazine assignments, and the attentions of many desirable women: Juliet, the hotshot business journalist; Elisa, Nate’s gorgeous ex-girlfriend, now friend; Hannah, lively and fun and ‘almost universally regarded as nice and smart, or smart and nice’.

In this twenty-first-century literary enclave, wit and conversation are not at all dead. But is romance? In

The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.

Adelle Waldman plunges into the psyche of a sensitive, flawed, modern man – to reveal the view of the new world from his garret window, and the view of women from his overactive mind.

Adelle Waldman is a freelance writer and book critic. She worked as a reporter at the

New Haven Register

and the

Cleveland Plain Dealer

, and wrote a column for the

Wall Street Journal’s

website. Her articles also have appeared in

The New York Times Book Review

,

The New Republic

,

Slate

,

The Wall Street Journal

, and other national publications. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.

A NOVEL

Adelle Waldman

To my parents, Edward and Jacqueline Waldman

To give a true account of what passes within us, something else is necessary besides sincerity.

—George Eliot,

Romola

1

}

It was too late to pretend he hadn’t seen her. Juliet was already squinting with recognition. For an instant she looked pleased to make out a familiar face on a crowded street. Then she realized who it was.

“Nate.”

“Juliet!

Hi.

How

are

you?”

At the sound of his voice, a tight little grimace passed over Juliet’s eyes and mouth. Nate smiled uneasily.

“You look terrific,” he said. “How’s the

Journal?

”

Juliet shut her eyes briefly. “It’s fine, Nate. I’m fine, the

Journal

’s fine. Everything’s fine.”

She crossed her arms in front of her and began gazing meditatively at a point just above and to the left of his forehead. Her dark hair was loose, and she wore a belted blue dress and a black blazer whose sleeves were bunched up near her elbows. Nate glanced from Juliet to a cluster of passersby and back to Juliet.

“Are you headed to the train?” he asked, pointing with his chin to the subway entrance on the corner.

“

Really?

” Juliet’s voice became throaty and animated. “Really, Nate? That’s all you have to say to me?”

“Jesus, Juliet!” Nate took a small step back. “I just thought you might be in a hurry.”

In fact, he was worried about the time. He was already late to Elisa’s dinner party. He touched a hand to his hair—it always reassured him a little, the thick abundance of his hair.

“Come on, Juliet,” he said. “It doesn’t have to be this way.”

“Oh?” Juliet’s posture grew rigid. “How should it be, Nate?”

“Juliet—” he began. She cut him off.

“You could have at least—” She shook her head. “Oh, never mind. It’s not worth it.”

Could have at least what? Nate wanted to know. But he pictured Elisa’s wounded, withering look if he showed up so late that all her guests had to wait on him to start dinner, heard her slightly nasal voice brushing off his apology with a “whatever,” as if she had long since ceased to be surprised by any new bad thing he did.

“Look, Juliet, it was great to see you. And you do look great. But I’ve really got to go.”

Juliet’s head jerked back. She seemed almost to wince. Nate could see—it was obvious—that she took his words as a rejection. Immediately, he was sorry. He saw her suddenly not as an adversary but as a vulnerable, unhappy young—youngish—woman. He wanted to do something for her, say something earnest and truthful and kind.

“You’re an asshole,” she said before he had the chance.

She looked at him for a fraction of a second and then turned away, began walking quickly toward the river and the adjacent strip of restaurants and bars. Nate nearly called after her. He wanted to try, at least, to put things on a better footing. But what would he say? And there was no time.

Juliet’s strides, as she receded into the distance, were long and determined, but she moved stiffly, like a person determined not to let on that her shoes hurt her feet. Reluctantly, Nate started walking in the opposite direction. In the deepening twilight, the packed street no longer seemed festive but seedy and carnival-like.

He got stuck behind a trio of young women with sunglasses pushed up on their heads and purses flapping against their hips. As he maneuvered around them, the one closest twisted her wavy blonde hair around her neck and spoke to her companions in a Queen Bee–ish twang. Her glance flickered in his direction. He didn’t know if the disdain on her face was real or imagined. He felt conspicuous, as if Juliet’s insult had marked him.

After a few blocks, the sidewalks became less congested. He began moving faster. And he began to feel irritated with himself for being so rattled. So Juliet didn’t like him. So what? It wasn’t as if she were being fair.

Could have at least

what

? He had only been out with her three or four times when it happened.

It

was no one’s fault. As soon as he realized the condom had broken, he’d pulled out. Not quite in time, it turned out. He knew that because he was not the kind of guy who disappeared after sleeping with a woman—and certainly not after the condom broke. On the contrary: Nathaniel Piven was a product of a postfeminist, 1980s childhood and politically correct, 1990s college education. He had learned all about male privilege. Moreover he was in possession of a functional and frankly rather clamorous conscience.

Consider, though, what it had been for

him

. (Walking briskly now, Nate imagined he was defending himself before an audience.) The party line—he told his listeners—is that she, as the woman, had the worst of it. And she did, of course. But it wasn’t a cakewalk for him, either. There he was, thirty years old, his career finally taking off—an outcome that had not seemed at all inevitable, or even particularly likely, in his twenties—when suddenly there erupted the question of whether he would become a father, which would obviously change everything. Yet it

was not in his hands

. It was in the hands of a person he barely knew, a woman whom, yes, he’d slept with, but who was by no means his girlfriend. He felt like he had woken up in one of those after-school specials he watched as a kid on Thursday afternoons, whose moral

was not to have sex with a girl unless you were ready to raise a child with her. This had always seemed like bullshit. What self-respecting middle-class teenage girl—soon-to-be college student, future affluent young professional, a person who could go on to do anything at all (run a multinational corporation, win a Nobel Prize, get elected first woman president)—what such young woman would decide to have a baby and thus become, in the vacuous, public service announcement jargon of the day, “a statistic”?

When Juliet broke the news, Nate realized how much had changed in the years since he’d hashed this out. An already affluent, thirty-four-year-old professional like Juliet might view her situation differently than a teenager with nothing before her but possibility. Maybe she was no longer so optimistic about what fate held in store for her (first woman president, for example, probably seemed unlikely). Maybe she had become pessimistic about men and dating. She might view this as her last chance to become a mother.

Nate’s future hinged on Juliet’s decision, and yet not only was it not his to make, he couldn’t even seem to be unduly influencing her. Talking to Juliet, sitting on the blue-and-white-striped sofa in her living room with a cup of tea—

tea!

—in his hand, discussing the “situation,” it seemed he’d be branded a monster if he so much as implied that his preference was to abort the baby or fetus or whatever you wanted to call it. (Nate was all for a woman’s right to choose and all the lingo that went with it.) He’d sat there, and he’d said the right things—that it was her decision, that whatever she wanted he’d support, et cetera, et cetera. But who could blame him if he felt only relief when she said—in her “I’m a smart-ass, brook-no-bullshit newspaper reporter” tone of voice—that, obviously, abortion was the natural solution? Even then he didn’t allow himself to show any emotion. He spoke in a deliberate and measured tone. He said that she should think hard about it. Who could blame him for any of it?

Well, she could. Obviously, she did.

Nate paused on a corner as a livery cab idled past, its driver eying him to see if he was a potential fare. Nate waved the car on.

As he crossed the street, he began to feel certain that what Juliet actually blamed him for was that his reaction, however decent, had made abundantly clear that he didn’t want to be her boyfriend, let alone the father of her child. The whole thing was so

personal

. You were deciding whether you wanted to say yes to this potential person, literally a commingling of your two selves, or stamp out all trace of its existence. Of course it made you think about how different it would be if the circumstances were different—especially, he imagined, if you were a woman and on some level you wanted a baby. Sitting in Juliet’s living room, Nate had been surprised by just how awful he felt, how sad, how disgusted by the weak, wanton libidinousness (as it seemed to him then) that had brought him to this uncomfortable, dissembling place.

But did any of it make him an asshole? He had never promised her anything. He’d met her at a party, found her attractive, liked her enough to want to get to know her better. He’d been careful not to imply more than that. He’d told her that he wasn’t looking for anything serious, that he was focused on his career. She’d nodded, agreed. Yet he felt sure the whole thing would have played out differently if he could have said to her, Look, Juliet, let’s not have this baby, but maybe some other, at some future point … But while he admired Juliet’s sleek, no-nonsense demeanor, that brisk, confident air, he admired it with dispassionate fascination, as a fine example of type, rather than with warmth. In truth he found her a bit dull.

Nevertheless, he had done everything that could have been expected of him. Even though he had less money than she did, he paid for the abortion. He went with her to the clinic and waited while it was being performed, sitting on a stain-resistant, dormitory lounge–style couch with a rotating cast of teenage girls who typed frenetically on their cell phones’ tiny keyboards. When it

was over, he took her home in a taxi. They spent a pleasant, strangely companionable day together, at her place, watching movies and drinking wine. He left the apartment only to pick up her prescription and bring her a few groceries. When, finally, around nine, he got up to go home, she followed him to the door.

She looked at him intently. “Today was … well, it wasn’t as bad as it could have been.”

He, too, felt particularly tender at that moment. He brushed some hair from her cheek with his thumb and let it linger for a moment. “I’m really sorry for what you had to go through,” he said.

A few days later, he called to see how she was feeling.

“A little sore, but okay,” she said.