The Love of My Youth

Read The Love of My Youth Online

Authors: Mary Gordon

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Romance, #Contemporary, #Contemporary Women

ALSO BY MARY GORDON

Fiction

The Stories of Mary Gordon

Pearl

Final Payments

The Company of Women

Men and Angels

Temporary Shelter

The Other Side

The Rest of Life

Spending

Nonfiction

Reading Jesus

Circling My Mother

Good Boys and Dead Girls

The Shadow Man

Seeing Through Places

Joan of Arc

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2011 by Mary Gordon

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to HarperCollins Publishers for permission to reprint an excerpt from the “Second Duino Elegy” by Rainer Maria Rilke, from

A Year with Rilke: Daily Readings from the Best of Rainer Maria Rilke

by Joanna Macy and Anita Barrows, copyright © 2009 by Joanna Macy and Anita Barrows. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gordon, Mary, [date]

The love of my youth / Mary Gordon.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-37977-1

1. First loves—Fiction. 2. Middle-aged persons—Fiction.

3. Rome (Italy)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS

3557.0669

L

68 2011 813′.54—dc22 2010032988

Jacket image: The Ponte Giuseppe Mazzini in Rome by Rob Koenen/Flickr/Getty Images

Jacket design by Carole Devine Carson

v3.1

For Penny Ferrer

We have come this far

This is given to us, to touch

each other in this way.

—Rainer Maria Rilke,

from the Second Duino Elegy

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Gail Archer and Richard Goode for advising me on matters musical. Also I would like to thank everyone who has opened to me the joys of Rome.

My time in Rome was made possible by research funds provided by the Millicent C. McIntosh Chair in English at Barnard College.

Contents

October 7, 2007

“I hope it won’t be strange or awkward. I mean, what seemed strange to me, or would seem strange, is not to do it. Because in a way it is strange, isn’t it, really, the two of you in Rome at the same time, the both of you phoning me the same day?”

Irritation bubbles up in Miranda. Had Valerie always been so garrulous? So vague? Had she, Miranda, always found her so annoying—the qualifications, the emendations, laid down, thrown out like straw on a road to muffle the noise of passing carriages when there’d been a death in the house? Where did that come from? Some novel of the nineteenth century. The early twentieth. And now it is the twenty-first, the first decade nearly done for. There’s no point in thinking this way, focusing on Valerie’s habits of speech and diction. As if that were the point. The point is simply: she must decide whether or not to go.

It has been nearly forty years since she has seen him. Or to be exact—and it is one of the things she values in herself, her ability to be exact—thirty-six years and four months. She saw him last on June 23, 1971. The day had changed her.

Adam tries to remember if he had ever been genuinely fond of Valerie. What he can recall is that, of Miranda’s many friends, Valerie was the one who seemed most interested in him. The one who asked him questions and then listened to his answers, who assumed he had a life whose details might be worthy of her attention. 1966, ’67, ’68, ’69, ’70, ’71. A time when he spent his days trying to determine the perfect fingering, the ideal tempo, for a Beethoven sonata, a Bach partita. A way of spending time that Miranda’s friends considered almost criminally beside the point. The point was stopping the war. Stopping racism. Stopping poverty. Diminishing the injustice of the world.

In those days, he couldn’t speak to anyone about his pain over the fact that Miranda seemed entirely taken up by the problems of the world. The things that absorbed him no longer captured her attention. Not that he ever wanted to

capture

her attention; her attention was not a bird he was trying to snare, a fish he was netting. For that was what he loved most about Miranda: her mind’s speed, but not only her mind, her quickness in everything. Darting, swooping, leaping, thrilling to him, who moved so slowly, whose every gesture was considered. Those who criticized his playing of the piano accused him of being incapable of lightness. She was a bright thing, a shimmering thing, a kingfisher, a dragonfly. Thirty-six years later she would be no longer young. Had she kept her quickness? Her lightness? Which would he have preferred, that she had kept or lost them?

Is that why he’s agreed to it, to seeing her after all these years, at this dinner Valerie has arranged? Out of simple curiosity? Along with lacking lightness, he has been charged with lacking curiosity. But perhaps both had always been untrue. That curiosity has in this instance triumphed over shame: this must be a sign of strength. For if his soul is, as he’d learned in Sunday school, a clear vessel that could be blackened by his sins, what he did to Miranda was among the blackest. When he told himself he couldn’t have helped it, that he had done the best, the only thing he could have done under the circumstances, the words rang false. He would be tempted to say that to her now, but he would never say it. He is hoping there will be no need. That they will see each other once again, no longer young but healthy, prosperous, intact. That he will see the proof: that he did not destroy her.

She stands before the spotted mirror. A dime-sized pool of expensive moisturizer—rose scented, ordered especially from a Romanian cosmetician in New York—spreads in the heat of her palm. Miranda wonders what Adam looks like. She tries on a long black skirt, throws it impatiently on the bed, then Nile green silk pants with wide legs. She tries on the black skirt again. Then a violet knit top, which she rejects because it emphasizes her breasts. Once a vexation to her on account of their smallness, her breasts had done all right with age. She’s glad he won’t be seeing her naked. Or in a bathing suit. Well, she is nearly sixty now, and her body shows the marks of bearing two strong healthy sons. Her legs, which, he had said, caused him a desire that was painful in its intensity when he saw them in her first miniskirt—September 1965—but which she’d always thought too thick, too straight, these had gone flabby. She’s tried—swimming, running, yoga—but nothing really helps. Most of the time she doesn’t think of it, she doesn’t really care. It’s one of the benefits of age: such things have lost their power to scald.

She’s blonde now; he would not be accustomed to thinking of her as a blonde, and her hair is short, boyish. In the time they knew each other her hair had hung down her back at one point almost to her waist. Her hair was brown then, a light brown; he’d called it honey colored. She’d parted it in the middle or braided it into a single plait. Then she remembers: he did see her, briefly, with boyish hair. She doesn’t like to think about that time.

She looks at the lines around her eyes, her mouth. Her face has not ceased to please her, but it could never be the face that he had loved.

He has read about her. An article he found in a doctor’s office. “Does Your Office Make You Sick?” Sick buildings. She is an epidemiologist specializing in environmental threats. Her sub-specialty: molds.

He thought that such work seemed ill suited to her. Quiet, painstaking work. Requiring patience, which she’d always lacked. But then he remembered: it was only with people that she was impatient. With the physical world, she held her quickness in check; she could spend hours looking, sorting.

He wonders how she does her work. Does she go around old buildings, masked, accompanied by young acolytes collecting things in closed containers, tiny bits of plaster prized from the walls with tweezers? He can imagine her sitting at a microscope, one eye glued to a lens, silent, looking. Or perhaps no one uses microscopes anymore. He knows nothing. Valerie told him—he was grateful that he didn’t have to ask—that she is married. A doctor, an Israeli; he is, Valerie said, something important in the California Department of Public Health. He learned this only days ago. Before that, if anyone asked, he wouldn’t have been able to answer the question,

What has become of her?

She would know nothing of what has become of him. She would never have read anything about him; he has done nothing that would have placed his name before the public. A music teacher in a private school. Director of the chorus. One day, he might be known as the father of his daughter, if she continues her early promise on the violin. But up to now, it would be accurate to say he’s done nothing worthy of note.

Miranda has heard something, vaguely, some tragedy about Adam’s wife. A suicide. She was not, to her shame, sorry. She would not ask details of Valerie. Even to say the woman’s name, even after all these years, would be an offense against her pride, and this, too, had seemed to her excessive. But it was an impulse she could not give up.

Bitterness.

Pride.

Grievance.

Of course it would be better to be free of them. Of course.

Ridiculous to feel it still all these years later. A sense of betrayal. A sense of abandonment. Two-thirds of her life. Sixty-six and two-thirds percent. She had had a thorough training in statistics; numbers are her friend, they have often made her point, they’ve told the truth, they’ve uncovered poisonous equivocations. How many years has it been since she’d even thought of Adam? And—what was her name. HER. She looks in the mirror and castigates herself for her own falseness, a falseness all the more ridiculous because it is for no one’s benefit but her own. She would never forget the name. That name. Beverly. Bev.

She tries the black skirt on again. Perhaps the white shirt would make her face too pale. Above all she must appear to have, over the years, flourished. A rose-pink camisole, then, and a jacket: small pink and white flowers against a background of black silk. Yes, that’s right. As a young woman she would never have worn pink, disliking what the shade suggested: weakness, girlishness. But she has grown to like pink. No one, she is certain now, would think of her as weak. Or take her for a girl.

Adam stands before the mirror that attaches to the front of his

armadio

, a looming and reproachful piece, reminding him of its glorious pedigree, hinting reproachfully of his current status (American and not wellborn), an interloper, taking the place of his betters because of Yankee dollars and the slow steady erosion of the values of the lovely past. The people who own the apartment can only afford to keep it because they rent it out most of the year. They live somewhere cheaper. Adam had asked Valerie not to tell him the details.

He moves closer to the mirror so that he can focus, not on his body, but on his thinning hair. No one could say that he was going bald—he is grateful for that—but his hair has lost its luxuriance and, once jet black, is gray now, and he keeps it cropped short to conceal the diminishment (yes, he’s admitted to himself it is a vanity, this effort at concealment). When he saw her last, his hair came down to his shoulders. It curled—his aunts would say, “Those curls are wasted on a boy. What I wouldn’t give to have them.” At least he isn’t so ridiculous as to wear a ponytail at his age, as some of his colleagues do, to the mockery of the more hostile, or more fashion-conscious, students. He can only imagine the contempt Miranda would have for men who wear ponytails. Even after all these years he is certain of it. And, feeling himself enlarged by the comparison that he has just invented, he relaxes about his hair.

Turning from the mirror, he glances at his hands. Nails round, cut short. Pianist’s hands. He has not achieved fame, success, even, but he has not given over his calling. She had loved his hands. She would kiss his fingers and turn his hands over one at a time, and kiss the palms. Her lips, moist, their touch preceded by a warm moist breath (he had found it quite unbearably arousing). “My darling love, my genius boy. What joy you bring with these wonderful hands. You make beautiful music. You make beautiful love. I hope to see your hands the last thing before I close my eyes in death.”

She was capable of speaking ridiculously like that. She was fifteen, sixteen, seventeen years old. She felt free always to overstate, to shed tears. To use terms that were too large: “genius,” “love,” “death.” He had a perfectly ordinary pair of hands. He was, for a serious pianist, only moderately gifted. As for his skill at lovemaking: there was no skill, no art … no notion that there was a better way. Or a worse. They were only two young people, ordinary in their youth, their ardor.

It was easier when he thought like that. But it was not the truth, and he would not dishonor the past, the two of them as young, by such a dismissal. In their innocence, in their belief in life and in each other, in the clarity of their desire that had no residue of punishment or will to humiliate or dominate or shame, they had been a thing of beauty. Valuable. Not ever, would he betray that. His youth. Their youth. She was the love of his youth. He is no longer young. And she, too, has lost youth. But he will not betray it.

He remembers dancing with Miranda for the first time. It was near Thanksgiving; he had not yet asked her out. Someone had a party in a basement, and although the air outside was taking on a chill, the air in the dark basement was thick with the sense of intense exertion and young lust, hanging like a curtain along with the residual smell of the family beer. He felt about to burst, burst into flame, with longing, longing quick as a flame spreading over a dry ground. A flame he could never imagine extinguishing, never going out. He remembered her writing down a word first because she liked it, second because she wanted to do well on her SATs. “Fulvous,” the word was.

No one at the party dreamed of doing more than kissing. Or perhaps the more adventurous might try touching a girl’s breasts. In six months, when many of them turned sixteen and the times they were a-changing, heated discussions among the girls would be the norm: how far could you let him go, after how long.

The first night when he danced with Miranda, holding her, he put his mouth against her hair and inhaled the exacting innocence of her shampoo. Clean, maddening. He did feel driven mad with desire, with shame, certain she could not be feeling anything like what he was feeling. When they were dancing, she lifted her chin so that a kiss would happen. It did not. He was too afraid.

Forty years later, he feels the clutch of gratitude. Never in Miranda was there the slightest hint, not the smallest suggestion, that he, male, was monstrous and she, female, shocked, pure. They shared ardor. It was she who suggested they become lovers. They were sixteen years old. Daring then. Now? So commonplace as to be unworthy of mention. They were sitting by the river and she said, “Adam, you need to know something. I want everything that you want, maybe more, maybe worse.” Was it possible that her skin was always warm, even in winter, as if she carried with her always some hint of early June? So he could leave behind the young man’s shame, like a coat he had grown out of. But not the young man’s desperation. Almost impossible to recall that desperation now. The urgency of a boy’s arousal. Now, at nearly sixty, he sometimes has to coax himself to be aroused by a lovely girl. And married sex? It satisfies, like a good meal, a fine painting. But desperation? Madness? Not now, never. He had asked his doctor for Viagra.

Miranda need never know that.

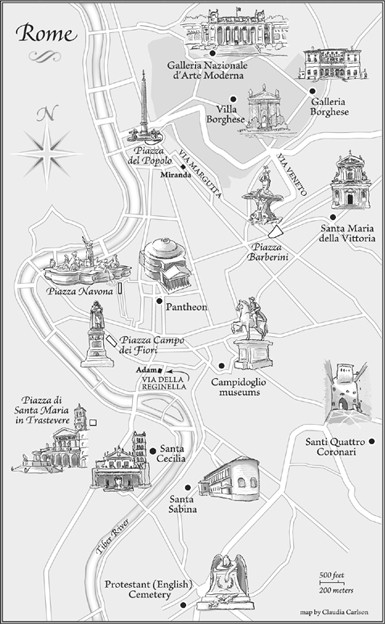

He turns the heavy archaic key with the gold fob shaped like a pinecone. He walks down to the Via della Reginella, a narrow street between the Piazza Mattei and the Ghetto, his hands in his pockets, weighed down by the heavy key, and lets his right hand travel over its complex indentations, the overornamented fob.

He has left the flat too early. He plans a route that in its indirectness will consume the extra time. He walks half a block in the wrong direction to the Fountain of the Tortoises, four elegant flirtatious boys, flaunting their nearly childish sex, playing with their near girlishness, arranging, seductively, the unserious angles of their limbs. As a boy he was, he knows, never elegant, and never dared to be flirtatious. If it weren’t for Miranda he might never have been a boy. Only a musician. Nothing like these marble creatures offering sex as if it were a perfectly good but unimportant joke.