The Lupus Book: A Guide for Patients and Their Families, Third Edition (14 page)

Read The Lupus Book: A Guide for Patients and Their Families, Third Edition Online

Authors: Daniel J. Wallace

save a finger, sympathetic blocks or sympathectomies (cutting the autonomic

Reactions of the Skin: Rashes and Discoid Lupus

[75]

nerves to the hand) are occasionally performed, but the results are often only

temporary. Ulcers limited to one finger can be differentiated from a lupus an-

ticoagulant-derived clot (treated with blood thinners; see Chapter 21), or cho-

lesterol clots called emboli (treated by lowering cholesterol levels). Blood testing and studies of the blood vessels are used to determine the exact nature of such ulcers.

Livedo Reticularis

Some 20 to 30 percent of all lupus patients have a red mottling or lacelike

appearance, or livedo reticularis, under the skin. Causing no symptoms, it in-

dicates a disordered flow in blood vessels near the skin due to dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system. Even though normal individuals may demonstrate livedo reticularis and no treatment is ever required, recent work has associated this condition with a secondary fibromyalgia, with the circulating lupus anticoagulant, or with anticardiolipin antibody. Livedo reticularis on rare occasions can lead to

livedoid vasculitis

, a condition that involves superficial skin breakage. This complication may be treated with steroids or colchicine.

Cutaneous Vasculitis, Ulcers, and Gangrene

Inflammation of the superficial blood vessels (those near the skin) is known as

cutaneous vasculitis

. Seen in up to 70 percent of patients with lupus during the course of their disease, this finding is a reminder that more aggressive management may be required in some individuals. These lesions often appear as red or

black dots or hard spots and are frequently painful. If untreated, cutaneous vasculitis can result in ulceration, or breakdown of the skin. This may lead to

gangrene, or dead, black skin. Gangrene from systemic vasculitis can be a limb-

and life-threatening emergency. Such a condition is usually the result of a clot from the circulating lupus anticoagulant or vasculitis of a deep middle-sized

artery; a prompt workup is vital to determine whether steroids, blood-thinning

agents, or both are warranted. Cutaneous vasculitis is treated less urgently with colchicine, medicines that dilate blood vessels, and corticosteroids. As with Raynaud’s, sometimes prostaglandin infusions are used. Vasculitic lesions are not

limited to the fingertips or ends of the toes; systemic vasculitis may produce

ulcers on the trunk of the body or on the extremities.

Black-and-Blue Marks (Purpura and Ecchymoses)

Black-and-blue marks that appear as blotches under the skin may result from

abnormal blood coagulation in patients with active lupus.

Purpura

is the term for this phenomenon. If the purpura is small and ‘‘palpable’’ (that is, feels

markedly different from normal skin when touched without looking), this may

[76]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

be a warning sign of active systemic vasculitis (see the previous section) or low platelet counts (called

thrombocytopenic purpura

). On the other hand, black-and-blue marks that cannot be felt may result from the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., aspirin, naproxen), or corticosteroids. Nonsteroidals can prolong our bleeding times; corticosteroids promote thinning and atrophy

of the skin, which can lead to the rupture of superficial skin capillaries (called ecchymoses).

This condition is not serious and is managed by reassuring the patient that it

does not represent a systemic disease process.

OTHER SKIN DISORDERS IN LUPUS PATIENTS

Unusual forms of cutaneous lupus may occur that are not necessarily associated

with any other aspect of lupus activity. Most are extremely rare, and only two

are briefly mentioned here.

Lupus Panniculitis (Profundus)

One out of 200 patients with lupus develops lumps under the skin and no ob-

vious rash. The ANA test of these patients is often negative, and the criteria for systemic lupus are not fulfilled. Under the microscope, biopsy of the skin reveals inflamed fat pads in the dermis with characteristic features of lupus. If untreated, the skin feels lumpier and atrophies. Known as

lupus panniculitis

or

profundus

, this rare disorder responds to antimalarials, antileprosy drugs (Dapsone), oral corticosteriods, and steroid injections into the lumps.

Blisters (Bullous Lupus)

For every 500 patients with lupus, one has bullous lesions. Looking like fluid-

filled blisters or blebs (large chickenpox marks), this complicated rash can be further divided into several different subsets. Resembling another skin disease called pemphigus, bullous lupus is also called

pemphigoid lupus

. A biopsy of the skin is essential, since treatment depends on which of the three types of

bullous rashes are present. Bullous lupus can be quite serious and on occasion

constitutes a medical emergency, since widespread oozing from the skin can

lead to dehydration and even shock. Systemic corticosteroids are frequently prescribed for this condition, as are antileprosy drugs such as Dapsone.

WHAT IS THE LUPUS BAND TEST?

Since 1963, skin biopsies have been improved by our ability to determine

whether a rash is mediated by the activity of the immune system, which is

detected by the presence of what are called

immune deposits

. At the junction of

Reactions of the Skin: Rashes and Discoid Lupus

[77]

Table 13.1.

Results of the Lupus Band Test

Positive Tests

Positive Tests in

Diagnosis

in Lesions

Normal-Appearing Skin

Systemic lupus patients

90%

50%

Discoid lupus patients

90%

0%–25%

Normal patients,

sun-exposed skin

NA*

0%–20%

Normal patients, non-

sun-exposed skin

NA

0%

* NA ϭ not applicable

the epidermis (top of the skin) and the dermis (the layer below the skin), we

can now see if immune complexes (see Chapter 6) have been deposited. Most

patients with immune disorders will have these immune complexes at the der-

malepidermal junction. Lupus is one of the few diseases in which the deposits

are ‘‘confluent’’ (that is, once stained with a fluorescent dye, the skin of lupus patients will reveal a continuous line).

To perform a

lupus band test

, as this procedure is called, a dermatologist takes a skin biopsy from both a sun-exposed area (e.g., forearm) and an area

never exposed to the sun (e.g., buttocks). These biopsies are then transported in liquid nitrogen and stained to detect specific immune reactants (IgG, IgM, IgA, complement 3 or C3, and fibrinogen) at a pathology laboratory. The biopsy is

relatively painless and leaves a small scar.

A confluent stain with all five reactants or proteins implies a greater than 99

percent probability of having systemic lupus; if four proteins are present, there is a 95 percent probability; three proteins, an 86 percent probability; and two proteins, a 60 percent probability provided that IgG is one of the proteins. In discoid lupus, only lesions (areas with rashes) display these proteins. In systemic lupus, most sun-exposed areas and some non-sun-exposed areas will display

these proteins.

Lupus band tests are performed for two reasons. First, the test can confirm

that a rash is part of an immune complex-mediated reaction, which would in-

dicate the need for anti-inflammatory therapy. Second, the test is performed

when a patient with a positive ANA test but nonspecific symptoms does not

fulfill all the criteria for systemic lupus but the physician feels strongly that a diagnosis must be made one way or the other in order to initiate treatment.

Table 13.1 summarizes the results of the lupus band test for groups of patients.

The musculoskeletal system is the most common area of complaint in lupus

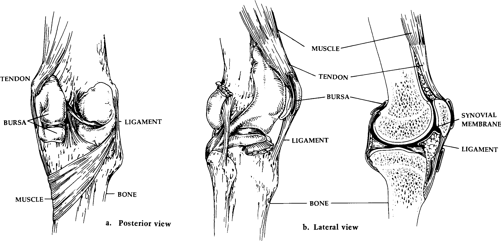

patients. This system involves different types of tissues: the joints, muscles, bone, soft tissues, and supporting structures of joints such as tendons, ligaments, or bursae. The reader may wish to refer to Figure 13.1 as these areas are discussed.

JOINTS AND SOFT TISSUES

Arthralgia

is used to describe the pain experienced in a joint;

arthritis

implies visible inflammation in a joint. Although we have over 100 joints in our body,

only those joints that are lined by synovium can become involved in lupus.

Synovium

is a thin membrane consisting of several layers of loose connective tissue that line certain joint spaces, as in the knees, hands, or hips. It is not found in the spine except in the upper neck area. In active lupus, synovium

grows and thickens as part of the inflammatory response. This results in the

release of various chemicals that are capable of eroding bone or destroying

cartilage. Inflammatory synovitis is commonly observed in rheumatoid arthritis

but occurs less frequently and is less severe in systemic lupus.

Surveys have suggested that 80 to 90 percent of patients with systemic lupus

complain of arthralgias; arthritis is seen in less than half of these cases. Deforming joint abnormalities characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis are observed in only 10 percent of patients with lupus. The most common symptoms of arthritis

in lupus patients are stiffness and aching. Most frequently noted in the hands, wrists, and feet, the symptoms tend to worsen upon rising in the morning but

improve as the day goes on. As the disease evolves, other areas (particularly

the shoulders, knees, and ankles) may also become affected. Non-lupus forms

of arthritis such as

osteoarthritis

and joint infections can be seen in SLE and are approached differently.

Fig. 13.1.

Anatomy of the Knee Joint

[80]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

Synovium also lines the

tendons

and

bursae

. Tendons attach muscle to bone; bursae are sacs of synovial fluid between muscles, tendons, and bones that promote easier movement. These are the supporting structures of our joints and are responsible for ensuring the structural integrity of each joint. In addition, bursae contain sacs of joint fluid that act as shock absorbers, protecting us from traumatic injury. Inflammation of these structures may lead to deformity if

ligaments

(tethers that attach bone to bone) or tendons rupture.

Trigger fingers, carpal

tunnel syndrome

, and

Baker’s cyst

(all described in the following pages of this chapter) are examples of what can result from inflammation in these areas.

Occasionally, cysts of

synovial fluid

may form. These feel like little balls of gelatin and are called

synovial cysts

. When a joint or bursa is swollen, it is often useful to aspirate or drain fluid from the area to ensure good joint function.

When viewed under the microscope, synovial fluid (fluid made by synovial

tissue) provides a great deal of diagnostic information. Its analysis usually focuses on red and white blood cell counts, crystal analysis (e.g., for gout), and culture (e.g., for bacteria). White blood cell counts of 5000 to 10,000 are common in active lupus; counts above 50,000 suggest an infection; counts below

1000 suggest local trauma or osteoarthritis. Normal joint fluid contains 0 to 200

white blood cells. Crystals of uric acid (as in gout) or calcium pyrophosphate

(as in pseudogout) are occasionally observed in lupus patients and necessitate

specific treatment modifications. Joint fluid may also be cultured for bacteria.

Viruses are rarely if ever tested for when cultures are taken (they grow poorly in cultures); but since viruses, fungi, parasites, or foreign bodies may complicate lupus, the analysis of synovial tissue obtained at synovial biopsy may also be

required in addition to synovial fluid cultures.

If no evidence of infection is present when a joint is aspirated, I usually inject a steroid derivative with an anesthetic (e.g., Xylocaine). This often provides

prompt symptomatic relief and successfully treats the swelling. Occasionally,

one joint may remain swollen despite anti-inflammatory measures. In these sit-

uations,

arthroscopy

(looking at the joint with an operating microscope) along with a synovial biopsy may be diagnostically useful. A persistent

monoarticular

arthritis

(arthritis in one joint only) implies either an infection, the presence of crystals, or internal damage (structural abnormalities) in the joint. The presence of

oligoarthritis

(inflammation of two to five joints) and

polyarthritis

(inflammation of more than five joints) suggests a systemic process. Joints are usually x-rayed before any diagnostic procedures are performed to make sure that no