THE LUTE AND THE SCARS (12 page)

Read THE LUTE AND THE SCARS Online

Authors: Adam Thirlwell and John K. Cox

Danilo Ki

š

(1935

–

1989) remains best known in his native Serbia and in the world of translation as a novelist. If one throws into his dossier the fact that his fiction was mildly (and bravely) postmodern and that the Holocaust was one of his main themes, we will have just about reached the end of our popular, journalistic understanding of the man and his works. Yet the refinement, even the reframing, of Ki

š

’

s profile continues as we move well into the third decade following his premature death of lung cancer in Paris. Recent years have seen the publication of more and more scholarly articles about the methods and themes of his works, as well as the translations of some additional stories, an early novel, and a play; in Serbia there are even new primary sources coming to light, such as the two Ki

š

film scripts, published in late 2011 as

Dva filmska scenarija

, and the occasional rebroadcast of his 1989 collection of filmed interviews in Israel with

“

double victims

”

of fascism and (early) Yugoslav communism,

Goli

ž

ivot

(Bare Life). The new trends arising from this publishing activity

—

trends that supplement but in no way supplant the basic Western critical understanding of Ki

š

originating in his

“

family cycle

”

of novels and stories and in the carefully selected, cosmopolitan essays brought out in the English-language version of

Homo Poeticus

during the war-torn 1990s

—

could arguably be summed up as increased attention both to the Yugoslav milieu depicted in his writings and to his artistic and ethical aversion to Stalinism. There are a number of other jewels awaiting their turn to speak to audiences in translation, and Ki

š

’

s life itself still awaits a great biography, in any language. The publication of this volume is, in my opinion, a bracing new chapter in Serbian and East European literature, and . . . one might add . . . it represents only a fraction of the excellent work that still remains inaccessible in English.

The seven stories contained in this version of

The Lute and the Scars

do not have an overarching common theme. They do, however, all very much bear the stamp of the author

’

s mind and touch. They are enjoyable, by turns intimate and politically obstreperous and sad and even funny, and their diversity will allow a fuller appreciation of Ki

š

’

s thematic concerns and, possibly, his stylistic approaches. One of the stories,

“

The Stateless One,

”

reflects themes explored elsewhere in Ki

š

’

s oeuvre

—

here, the difficult relationship of an artist to his work and skepticism about modern nationalism

—

though, even so, it is unique in choosing a (real) late Habsburg novelist as its protagonist.

“

Jurij Golec

”

is a touching and elegiac treatment of the last days and legacy of a Soviet refugee writer in Paris; it is without doubt one of this translator

’

s favorite stories in the volume, by dint of its alternating tones of sadness and levity, as well as its serving as a reminder of the existence of a little-known Holocaust novel, Piotr Rawicz

’

s

Blood from the Sky

, which ranks alongside key works by Aharon Appelfeld, David Grossman, Aleksandar Ti

š

ma, and Ki

š

himself among the indispensable fictional treatments of Nazi genocide.

“

Jurij Golec

”

is also the cosmopolitan equivalent of the very Yugoslav and very political account of a man of letters driven to desperation by ideological and physical brutalization at the hands of the secret police that we find in

“

The Poet.

”

Also rooted firmly in the Serbian context, and beautifully and humanely demonstrating Ki

š

’

s respect for Nobel Prize-winner Ivo Andri

ć

, for whom he had enormous but seldom discussed admiration, is

“

The Debt,

”

a stream-of-consciousness final will and testament of the great writer in his final days in the hospital.

“

A and B

”

is a short but challenging autobiographical essay that condenses many of Ki

š

’

s unconventional views about the

“

brutality

”

of Central Europe and the nobility of the Balkans (an inversion of the typical epithets); this is also the thematic register of his great novels

Garden, Ashes

and

Hourglass

. Finally,

“

The Lute and the Scars

”

is another colorful autobiographical piece that depicts bohemian Belgrade in the 1950s, the cold, lingering Stalinism of the USSR, and the struggle of a young writer to find authenticity and maintain personal integrity.

“

The Marathon Runner and the Race Official,

”

also bearing the imprint of inimical Soviet conditions, memorializes the precariousness

—

the mortal condition of being pitilessly

“

exposed,

”

if you will

—

of the marginalized and marked outsider: Ki

š

’

s preferred formula for the concept of

“

victim.

”

Each of these stories is anchored in Ki

š

’

s biography or in literary history more generally.

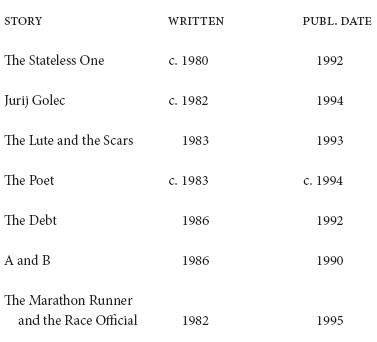

For an overview of the complicated genesis of the stories in this volume, the following table has been assembled from the original notes provided in the Serbian edition.

Readers will perhaps find it useful to stay attuned, while immersed in these stories, to conceptions of

“

home,

”

to various ways of embodying and depicting the

“

creative life,

”

and to the corrosive effects of dystopian dictatorships. The stories do at times have a lyricism that approaches the inimitable writing in the stories of

Early Sorrows: For Children and Sensitive Readers

; they are, on the other hand, nowhere near as bloody as, and by and large not as harrowing as, the stupendous component tales of

A Tomb for Boris Davidovich

. They have enough of the virtues of these other story collections to elicit a strong reaction from readers, however, and they also read like

“

vintage Ki

š

”

: to wit, the compression, the enumeration, the poignant detail, and the restlessly conversational language. The stories also offer us a chance to embrace a more fully Yugoslav, or Serbian, Ki

š

. The deep affection for Ivo Andri

ć

and, metaphorically, the acknowledgement of the author

’

s own set of

“

debts,

”

is every bit as much

“

the real Ki

š

”

as the cosmopolitan-ism

—

an artist

’

s search for authenticity and intuitive acceptance of diversity and intellectual and emotional (as opposed to political or ethnic) affinity

—

of

“

The Stateless One.

”

Likewise, the reflections on Yugoslav conditions in

“

The Lute and the Scars

”

and in this translator

’

s other favorite story in the collection,

“

The Poet,

”

are just as real as his many nonfiction pieces on French symbolism, Thomas Mann, and James Joyce. Finally, the looming presence of the USSR in so many of these stories reminds us that the political coloration of the backdrop to Ki

š

’

s life changed, significantly, from black to red before his teenage years were out. This epic turn left its indelible marks on his intellectual biography, and it precipitated neatly into that most engaging of his plays,

Night and Fog

(see

Absinthe: New European Writing

12 [2009]: 94

–

133).

* * *

These stories are deceptively complex, and their publication history is also complex. Therefore they received a good and necessary measure of critical attention and analysis as they were published

—

hence the indispensability of notes in and on the tales themselves. The original published notes to the stories can be found at the end of this volume.

The basis for the translations of the first six stories is the collection

Lauta i o

ž

iljci

, edited by Mirjana Mio

č

inovi

č

and published by the Beogradski izdava

č

ki-grafi

č

ki zavod (BIGZ) in Belgrade in 1994. For the provenance of the final story in this collection,

“

The Marathon Runner and the Race Official,

”

please see the notes at the end of the book.

I owe a debt of real thanks to the following friends for their help with various aspects of these translations: Predrag and Tamara Api

ć

, Jessica Blissit, Sara Brown, Pascale Delpech, Ken Goldwasser, Bea and Wolfgang Klotz, John McLaughlin, Dragan Miljkovi

ć

, Mirjana Mio

č

inovi

ć

, Jeff Pennington, Dan Shea, Predrag Stoki

ć

, Aleksandar

Š

tulhofer, Verena Theile, Gary Totten, and Milo Yelesiyevich. From books and encouragement to food, friendship, and fine points of vocabulary, these wonderful people have made bringing stories by Ki

š

to an anglophone audience into a very satisfying adventure.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Murlin Croucher. He was a mentor to many of us in the field of East European and Russian studies, an accomplished librarian, a universal wit and seeker, one pug-crazy dude, a lover of great literature wherever it was to be found, and my friend since 1987.

Requiescat in pacem

.

JOHN K. COX, 2012

Original Notes

These explanatory notes, a kind of critical apparatus for the individual stories in this collection, were written and first published by Mirjana Mio

č

inovi

ć

. The vast majority of them have been translated from the first edition of

Lauta i o

ž

iljci

(published in 1994 by BIGZ in Beograd). There are four exceptions to this attribution. The last sentence in the entry for

“

The Lute and the Scars

”

and the final three paragraphs of the entry for

“

The Poet

”

are additions taken from the 1995 edition of

Skladi

š

te

. In the notes to

“

The Debt,

”

the comparative material on Eug

è

ne Ionesco is also from

Skladi

š

te

. The entire entry for

“

The Marathon Runner and the Race Official,

”

like the beginning and end of the story itself, was taken from the subsequently published French and German editions of the story, since I have not yet seen a Serbian edition.

—

JKC

General Remarks

The stories from Ki

š

’

s literary estate entitled

“

The Stateless One,

”

“

Jurij Golec,

”

“

The Lute and the Scars,

”

“

The Poet,

”

and

“

The Debt,

”

all of which we are bringing out in this volume, originated in the years between 1980 and 1986, connected more or less directly with the book

The Encyclopedia of the Dead

. We have supplemented these with the short two-part prose piece

“

A and B,

”

which in manuscript form had no title. Although it does not seem to fit the definition of

“

short fiction,

”

it does function in a metaphoric (and metonymic) way in relation to the larger body of Ki

š

’

s work in prose: hence its place in this collection, and its position at the end, as a sort of

“

lyric epilogue.

”

The stories

“

Jurij Golec

”

and

“

The Poet

”

are being published here for the first time. The others have already been published in this order:

“

A and B

”

in the book

Ž

ivot, literatura

(Svjetlost, Sarajevo, 1990);

“

The Stateless One

”

in

Srpski knji

ž

evni glasnik

(1992, vol. 1);

“

The Debt

”

in

Knji

ž

evne novine

(1992, pp. 850

–

851); and

“

The Lute and the Scars

”

in

Nedeljna borba

(April 30

–

May 5, 1993).

In giving to this book the title

The Lute and the Scars

, we were guided by the fact that Ki

š

named two of his three collections of stories after one of the collected tales themselves; he did so less because of the story

’

s privileged position in its collection than because of the ability of the title itself to bring thematic unity to the other stories. It seemed to us that we could accomplish something similar with this title, in addition to enjoying its inherently paradoxical quality.

The Stateless One

The story

“

The Stateless One,

”

which comes down to us in

“

in-complete and imperfect

”

form, was inspired by the life of

Ö

d

ö

n von Horv

á

th. It will not be difficult for the reader to comprehend the reasons for Ki

š

’

s interest in this

“

Central European fate

”

that ended in such a bizarre manner on the Champs-

É

lys

é

es on the eve of the Second World War:

Ö

d

ö

n von Horv

á

th died on June 1, 1938, during a storm that descended abruptly on Paris, obliterating trees and sweeping away everything in its path. A heavy branch took

Ö

d

ö

n von Horv

á

th

’

s life, right in front of the doors to the Th

é

â

tre Marigny. He had arrived in Paris after an encounter with a

“

premium fortune-teller

”

in Amsterdam, who had prophesied that an event awaited him in the French capital that would fundamentally alter his life! (It is also easy to recognize the figure of an unnamed poet who plays an indirect but important role in this story: Endre Ady, whose life and literary fate was intertwined in similar ways with those of both Horv

á

th and Ki

š

. In this sense,

“

The Stateless One

”

is in some of its passages a condensed replica of parts of Ki

š

’

s story

“

An Excursion to Paris,

”

which dates from 1959 and was dedicated to Ady.)

Ki

š

first obtained translations of some of Horv

á

th

’

s plays in 1970. These were the French versions that Gallimard published in 1967 (namely

Italian Night

,

Don Juan Comes Back from the War

, and

Tales from the Vienna Woods

), prepared with an introduction that provided French readers with basic information about the life of this writer who had been utterly unknown up to that point. At this point Horv

á

th began appearing in Ki

š

’

s

“

warehouse

”

of emblematic figures and

“

themes for novels, topics for stories, parallels . . .

”

But ten years would have to pass (this was the decade in which he wrote

Hourglass

,

A Tomb for Boris Davidovich

, and

The Anatomy Lesson

) before the fate of this

stateless man

, which was attractive for reasons far exceeding mere literary interest, would again come to the front of Ki

š

’

s mind. For it was in 1979 that Ki

š

began his ten-year long

“

Joycean exile,

”

at the end of which, as was the case with Horv

á

th as well, came death in Paris. A further, external stimulus came from a recently published doctoral dissertation concerning history and fiction in Horv

á

th

’

s dramas (Jean-Claude Fran

ç

ois,

Histoire et fiction dans le th

é

â

tre d

’

Ö

d

ö

n von Horv

á

th

, Presses Universitaires de Grenoble, 1978). On an unnumbered page of the manuscript of

“

The Stateless One,

”

we find the following:

A story about the

apatride

or the Man Without a Country has been an obsession of mine for years. Actually from the time I read a short note in a magazine about his life and his tragic end. At first I had in mind writing some kind of retrospective or scholarly study about him. I wrote down a few observations, some of those na

ï

ve notes in which you conceal your own thoughts behind your characters. That was all really just appeasing my conscience and the creation of an illusion that notes like that are the beginnings of stories, their nuclei, the load-bearing beams of a future prose construction. But of course I got no further than that. And then one day I came across (by accident?) a PhD thesis that dealt with my stateless man. His character came back to life for me at once. And what did I find in this dissertation that related to my hero? A mass of useful information, dates, facts; but my story, my imaginary story atomized. The secret and mysterious atmosphere enveloping the life and death of my

“

hero

”

dissipated abruptly. But I nonetheless resolved to persevere, to try to bring back the atmosphere of secrets and the unknown. To write according to my own lights the bare-bones framework of facts, similar to a net of squares made of intersecting words.

(This passage, unchanged, could have formed part of a Postscript to

The Encyclopedia of the Dead

. It was probably written with that goal in mind.)

In manuscript form among Ki

š

’

s papers were preserved seven tables of contents of a book of stories that would be published in 1983 under the title

The Encyclopedia of the Dead

. The first two, which we can trace without difficulty to the year 1980, included the title

“

Ö

d

ö

n von Horv

á

th,

”

with a notation of the number of pages envisioned (ten in the first table of contents, and eight in the second). Both of the tables were written out by hand on half-sheets of typewriter paper. A remnant of cellophane tape attests to the fact that the list of titles (as if it were some literary duty) had been hung up in plain view somewhere. No tale involving

Ö

d

ö

n von Horv

á

th under any title, however, is to be found on the other five tables of contents, all of which were typed and which contain the titles of finished stories. We did, however, find forty-seven typed pages in Ki

š

’

s papers belonging to a

“

topic for a story

”

about the life and death of an

apatride

. One of them bears the title

“

APATRIDE

/MAN WITHOUT A COUNTRY,

”

typed in all capitals, and below that, in parentheses,

“

OUR HOMELAND IS THE MIND.

”

We used the first, underlined word as the title of the story, regarding the other two titles as variants. Among the forty-seven mostly uncorrected pages, we were able to discern two entities; their relationship to each other was one of

first

and

second versions

. The first consists of fourteen numbered pages, with traces of corrections, apparently carried out in one sitting, with a fine-point black pen. The story of the stateless man, now bearing the name Egon von N

é

meth (the exchange of the surname Horv

á

th for N

é

meth, aside from purely literary concerns, which lie outside the scope of these notes, is interesting in its own right: one common family name used to designate Hungarians living along the borders to Croatian areas has been traded for an equally common family name for Hungarians from border areas next to German-speaking territory), flows continuously in this version, without any kind of breaks, even among sections that are chronologically very far apart. In the text, however, there are fragments, designated by numbers and circled in the same black pen, that later, with almost no changes, appear in the second version of eight pages.

This second version comprises fifteen numbered sections. There is no title on the first page, something that could mean that this version served above all as an investigation of the suitability of the form: the fragment as a structural unit is being put to the test. The question of structure is again of the greatest importance: the sequence of sections (

“

the texture of events

”

), their dimensions, the relationship between their relative lengths, interruption in the course of the narrative, and the nature of their graphic representations (characteristic here is the absence of long passages: every section has the semantic density of a stanza of poetry). At the top of the first and second sections there are, in addition, typed sentences taken word for word from scientific texts. A possible function of these quotes: the contribution to a sense of compression; but they have another, more important function: it is as if the author of

A Tomb for Boris Davidovich

wanted, through them, to say the following:

“

Look, ladies and gentlemen, what my starting point is, and look what it gives rise to, no matter how

‘

carefully

’

I exercise my

‘

creativity.

’

”

What about the contents of the remaining twenty-five pages? For the most part unpaginated, they are largely variants of the passages included in the two versions already mentioned. But there are those that show

“

first-hand

”

traces of events from the life of the

apatride

that encompass his entire history. We took it upon ourselves, not without trepidation, to piece the story together (the fragmentary character of the second version made our work easier). We found justification in our desire to defy the irreversible.

Textual Notes:

entirely vague and pointless

: Sentence incomplete.

And so forth

: A passage for which we could unfortunately find no place in the unified and recomposed

“

variant,

”

given its similarity to this section/fragment, but could no more dispense with, on account of its function in the course of the narrative, is reproduced in its entirety here:

Here, in Amsterdam, in an isolated street a stone

’

s throw from a canal, our stateless man would suddenly find himself among his characters, a word that he used, not without attendant irony, every time his eye was drawn to those human creatures who bore on their faces or their bodies signs of rack and ruin, either patent or hidden. When night had begun its descent onto the streets, around the corner there would suddenly appear women, all dolled up, leaning against the wall in their tight, clingy dresses.