The Madagaskar Plan (51 page)

Read The Madagaskar Plan Online

Authors: Guy Saville

Stampede.

* * *

The accordion had finally stopped. The two alarms were ringing out of sync, one filling the other’s silence, like the wail of babies demanding their mother, thought Madeleine.

At first she marveled at Salois’s composure; then it unsettled her. He sat watching the soldiers below, while she flinched with every axe strike, struggling not to yell. Each time steel bit into wood, it sent sickening vibrations through the structure. The whole tower trembled.

“How can you be so calm?” she shrieked.

Through the broken slats at her feet, the soldiers seemed oblivious to the alarms and the burning barracks. They were too drunk to be accurate, the axeheads landing above or under the point they were chopping. One of the soldiers laughed so hard he had to give up. He staggered to a corner to vomit. The Untersturmführer stood apart from the others, his stare burning into her.

Salois replied as if he had been deep in thought and only just been roused by her voice. “Your husband—”

“He’s not my husband.”

“Cranley called me ‘the invincible Jew.’ I am death’s orphan: it doesn’t want me.”

“Tonight you’re wrong.”

“I’ve tried harder than this to die.” He offered her a wan smile. “I’m meant to live: it’s my punishment.”

A cracking sound; the tower began to dip forward.

“Punishment for what?”

There was a pause in the

chop-chop-chop

of axes, followed by a cheer. The groan and strain of timber; wood splitting. The crews fled their positions to watch the tower fall. It leaned over, plunging several meters—Madeleine screamed—then jolted to a stop. The gap between it and the steel water tower had narrowed but was still too risky.

Madeleine and Salois clung to the platform. He grasped her hand, encouraging her to crawl to the far side to counterbalance the weight. His manner was oddly careful and made her think of old couples, the way her father might have supported her mother’s arm if their world hadn’t been wrenched away.

The soldiers returned to the legs, seizing their axes.

Salois kept his voice low: “I did something…” He searched for a word as though he’d often thought about it and had too many to choose from. “Something wicked. Death would be too kind. Living is my penance.”

“What could you have done”—Madeleine was surprised by her own anger—“with everything on this island, what could you have done to believe that?”

“I’ve seen too much loathing, Madeleine, to want yours.”

“I haven’t got any more to give.”

His reply was so soft she had to lean closer to hear. “I killed my wife … or the woman who was going to be my wife.” His voice was tender and tearless.

Madeleine remained close. “An accident? It can’t be worse than here.”

“A fit of rage.” Something irreparable churned in his expression. “That’s why I never held my child. She was pregnant.”

The depth of his misery, of his self-disgust, was painful to hear—yet she didn’t recoil. Madeleine didn’t understand the catastrophe of his life but instinctively wanted to forgive him for it. She couldn’t explain why. It was as if the God she didn’t believe in had whispered in her ear. In a world that shunned atonement, Reuben Salois was determined to walk alone and be held to account.

A roar went up from underneath, something starved and berserk. The workers had broken free of their barracks and were running headlong into the soldiers, attacking with fists and wooden planks.

Salois slid to the ladder. “This is our chance.” He began to descend, Madeleine following.

Amid the fighting, the Untersturmführer snatched up an axe and swung it in a frenzy. Madeleine sensed each blow through the rungs. The tower began to buckle and splinter, pitching again. It toppled over, accelerating—then crashed to a halt, its fall broken by the other tower. Madeleine dangled from the ladder, her legs loose inside her dress.

Salois dropped below. The Untersturmführer swiped his axe at him, the blade cutting through the rain. Salois leapt back and, as the Untersturmführer lost his balance, tackled him to the ground. He joined his fingers together and brought the club of his fists down onto the Nazi’s face, fighting as if he truly believed in the conviction that he wouldn’t die.

Madeleine let go of the ladder, landing hard. She felt spikes in her hips and rolled into the sluicing mud. A noise filled her ears, like from the abattoir when animals were taken to slaughter and one of them sensed what was about to happen.

She stood—and was knocked off her feet by a charge of pigs.

Hundreds swept past her. She was beaten and knocked around by a blur of hogs until she was dragged back into the air by Salois. In one hand he held a machine gun; with the other he encouraged her to run. For several moments she was too dazed and breathless to do anything but comply. Then she realized they were following railway tracks, heading into the darkness.

“What about Abner?” she said.

“He’ll find us.”

She ran, soaked to the skin and lit with energy. The night held the promise of finding the twins.

Madeleine … Madeleine!

The cry that had haunted her since Antzu echoed through the rain. She blocked her ears to it. Salois spun round and let off a short volley.

She heard the voice again: closer, more fraught, with nothing supernatural in its pleading.

“Maddie,” it gasped, “stop.”

Madeleine faltered, glancing over her shoulder, incredulity washing through her. An impossible, poisonous hope that had no place in reality.

A solitary figure was running toward them, a silhouette emerging from the lights of the farm, indistinct through the shimmer of the rain, pigs at his heels. His body was lean and weary; she couldn’t make out his face. He ran between the tracks, the rails catching the light so they gleamed like beams of platinum.

Salois took another shot, the bullets sparking off the tracks near the feet of their pursuer, spitting flecks of stone at him.

Then another cry—resonant with a distant autumn morning; the call of a legionnaire as he approached a fort. She stopped dead, her heart cartwheeling. Salois lowered his weapon with a frown of expectation.

“

Ami! Ami!

”

* * *

Burton’s smile showed exhaustion but was crinkled with relief and a boyish exuberance. It faded almost at once.

Madeleine was bewildered.

Shocked.

She stepped back from him, her body tense—ready to bolt. Up close she was more wasted than the glimpses he’d had of her in Antzu, the light in her eyes dim; the corners of her mouth looked cracked and sore.

“Please,” he said, “no more running.”

She shook her head in violent disbelief. Pigs streamed to either side of them.

Every day as a boy Burton imagined the homecoming of his mother and the joy of seeing her again. He would skip and holler, grab her hand and drag her to the strawberry patch he’d cultivated, making her taste the fruit even if the berries were hard and white as pebbles. But if she had emerged from the jungle after years of absence, maybe his reaction would have been the same as Madeleine’s.

A crushing weariness settled on Burton. He wanted to wrap himself in Maddie and sleep till they were old. Then he thought of Bel Abbès, the Legion fort that had been his home for so many years.

If you returned to it from the west, your first glimpse would be from the peak of Faîte du Pierre. It was most beautiful at dawn: the air cool, a saffron light creeping up the battlements. Burton always checked his fatigue at that point: between him and a bed, cooked food, and fresh water were still twenty miles of unforgiving desert.

Madeleine’s eyes were busy, one moment resting on his face, the next falling on his ragged uniform. She reached out and touched him, tentative at first, tracing the shape of his skull as if she were blind. Her fingers brushed his brow and ran down to his jawbone. Then she was pinching his cheek, digging her nails into his flesh, convincing herself that he was real. Burton let her do it till it stung, then removed her fingers.

Tears ran down her cheeks. “Jared showed me your name. He swore you were dead.”

“He lied.”

A burst of laughter; Burton smelled the salt of her tears. Maddie held out her hands for his. He hesitated, offering only his right. He didn’t want her to see his stump—not yet. Burton wanted to pretend that all of him had returned.

Footsteps rang out on the tracks. Abner caught up with them, splattered in mud, his backpack hanging heavily on one shoulder.

“They’re launching helicopters,” he panted before telling Madeleine, “I found him for you. In the pig shit.” Burton detected a hint of satisfaction in his tone.

Salois joined them. “You get the rest of the explosives?”

Abner nodded.

“Then let’s go.”

The floodlights made Madeleine’s skin look overexposed. Her eyes had shed their fear and were bright with wonder. Burton slipped his fingers between hers—they were bonier than before, the skin tough—and they fled: away from the light, back toward the darkness.

“I’m taking you home,” said Burton.

“No.” She looked possessed. “To Mandritsara.”

If you know what hurts yourself, you know what hurts others.

Malagasy proverb

Nachtstadt

20 April, 23:50

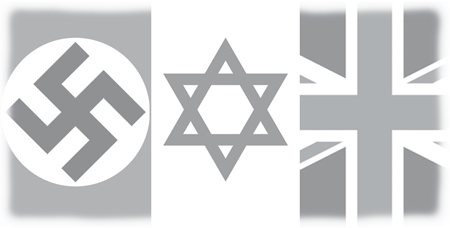

DEAD SWINE LITTERED the ground, the scene lit as starkly as a Nuremberg stadium. When the Jews had realized that they were defeated, they had begun killing the animals: stabbing, battering them with planks, cutting their throats. Many of the carcasses had Stars of David carved into their flanks.

“Fucking savages,” Globus said.

He walked alone through Nachtstadt, inspecting the carnage. At first the farm commandant and his officers accompanied him, shaking their heads and groveling, their breath rich with alcohol. Globus soon tired of their presence and dismissed them. They were mostly Vitamin B boys; he often did favors for people in Germania, making sure their sons got soft postings. If he returned to Europe in shame, he hoped those same people would remember him. It had stopped raining, and there was a glistening hush to the farm. The puddles rippled occasionally as though sighing. From roofs came a

drip-drip-drip.

He couldn’t get that sound out of his head. It was his future—Ostmark and the mansion he dreamed of building—running away.

Wherever he went, Himmler’s prized pigs lay slaughtered. Globus had seen enough animals at the end of a hunt to know that they often lay dead with open eyes and a curl to their lips—but every last pig seemed to be grinning as if it were in on some joke.

He was the butt of it.

The Reichsführer would be devastated, enraged, at the loss of Nachtstadt. Buildings had been burned, fences torn down, the veterinary hospital wrecked. It was a tiny but lucrative part of Himmler’s private business empire, and he took a personal interest in its operation, experimenting with the latest livestock-raising techniques. Prize specimens were regularly shipped to his Wewelsburg castle for banquets.

I enjoy roasting Jew pigs,

he would tell guests, dabbing away the laughter. If Globus admitted what had happened here, he might as well admit to being no better than Bouhler, the first governor. Everyone remembered how his career ended.

Globocnik let out a sob. It was the same terrible sob that had erupted from him when his wife miscarried, their child growing deformed inside her; even the experts at Mandritsara had been unable to save the baby. Instinctively, he hadn’t shared the news with Himmler when his wife first became pregnant.

He stopped in front of a pile of dead animals, all with Jewish stars sliced into their hides, and mulled over the graffiti painted on the Sofia Dam. If what happened in Nachtstadt was repeated in the reservations, he wouldn’t have enough troops to cope. The only chance of controlling such an uprising would be to open the floodgates. But what had the Reichsführer repeatedly warned him? The gates could be disabled.

The thought buzzed in his head like a mosquito.

Globus picked his way through the carcasses to the main square. He was still wearing spurs, though they were clogged with mud and silent. The tables were covered with bowls of potato salad and purple cabbage swilling in rainwater. At least those pigs left alive would feast in the morning. Globus snatched up a bottle of wine, went to drink, then changed his mind. He threw it away, the shattering glass his first moment of pleasure since the dungeon in Tana. The itchy sensation that Hochburg was responsible for all his woes crawled over him again. Hochburg, who had deprived him of manpower; Hochburg, who’d wrought disaster for him at the Ark and Antzu; Hochburg, with his Jew secrets and fear of America. It had taken two hours to fly from his palace. Globus came in a Walküre, leading a formation of other gunships. The pilots were disappointed when they arrived and found that order had been restored. He should have caught up on some sleep during the flight, but his recent injection coursed through his bloodstream and the radio crackled ceaselessly in his ears with news of more outrages across the island.