The Malice of Fortune (39 page)

Read The Malice of Fortune Online

Authors: Michael Ennis

Tags: #Thrillers, #General, #Historical, #Fiction

So this night did not bring sleep, but neither was it endless. Still holding Damiata to me, I watched the dawn trace gray lines through the shutters of our small window. Shortly after, sound also seeped into our little sanctuary, but this was not the great mill wheels of fate grinding into motion or even the rising of the little city. It was a gentle buzz, as if several people were conversing just beneath our window or outside our door.

I got up and dressed; I had on my cape before Damiata opened one eye in fetching fashion and smiled at me. I told her, “The army may be preparing for something.” I was deliberately vague, not wanting to suggest what I most deeply feared, that Valentino’s dwindling troops were preparing to leave Cesena and proceed south, to join the superior forces of the

condottieri

. “I’ll go out and see.”

I descended to the icy street, finding the sky as gray as an oyster shell. A few lonely snowflakes still drifted down. Past the next corner several be-caped workmen crunched hurriedly along, but otherwise the street was empty. The sound that had drawn me outside, however, was more evident, a murmur that seemed to come from the vicinity of the piazza. A crowd, issuing a quiet and reverent soughing.

Crossing several streets, I reached the piazza, which opened up before me in a single blink, teeming as if the entire city had been summoned there. I did not need to inquire as to the reason for this gathering. The tower of the

rochetta

stood like a Titan in the pit of Hell above a lake of dark wool hoods and fur caps. And the condemned man would soon appear, I was certain, in its highest window.

Among the sea of caps I observed Leonardo da Vinci’s conspicuous gray mane, close enough to the foot of the tower that he risked being kicked in the head when the condemned man reached the end of his rope. As I made my way toward him, I was struck that the collective tenor of the crowd altered, the farther I ventured into this lake of men. The hushed speculation in guttural Romagnolo I heard at the periphery gradually gave way to whispered, anxious prayers, and then to the sort of awed silence usually inspired by the shroud of Christ. I had entered this region of mute reverence, although I was still eight or ten

braccia

from Leonardo, when I saw Ramiro da Lorca.

His closed eyes were so swollen and discolored that it appeared plumbs had been stuck into the sockets. The rest of his blocky face was covered with bruises, each the artifact of a question that had not been answered—or an answer that had demanded another question. I had advanced two more paces when I observed that the sole support of Ramiro’s battered head was a pike fixed into the meat of his truncated neck.

Stunned by this grim vision, not to mention the death of my hopes, I was unable to appreciate the entire spectacle until I had almost reached Leonardo. A simple linen mat had been placed over the new snow, just beneath the sheer massif of the tower. On this canvas lay Ramiro’s body, still attired in an expensive brocade robe, beside it a butcher’s block and a bloody cleaver with a blade as long as my forearm.

With his gray hair and drawn face, Leonardo was of a piece with a world that appeared entirely ashen. I did not think he had even noted my arrival, until he turned and said at once, “You must come with me. I have succeeded in explaining everything.”

CHAPTER

14

N

othing is worthier of a warrior than to foresee the designs of his enemy

.

So quickly did Leonardo’s lunging steps lead me across the little city, that I found myself in his warehouse, lit like springtime by his globe lamps, as if I had been flown there on the back of a goat. We stood before one of his banquet tables, now littered with an accumulation of geometric models such as learned men keep in their

studioli

: cones, cylinders, and more elaborate, many-sided forms made of paper or thin shaved wood.

Directly beneath us was a machine, this consisting of a wooden box about a palm in height and a

braccia

long and wide, with a rod and a small crank protruding from one side. Atop this box was a flat, round, platter-like piece of wood almost as wide as the box itself, with a shiny surface like a potter’s glaze. The round wooden plate did not appear to lie directly upon the top of the box but seemed to be suspended just above it by an axle in its center, like the wheel of a cart that has been tipped on its side.

I was scarcely surprised that Leonardo did not at once explain the purpose of the contraption. Instead he extended one of his great crane-wing arms and gathered up a volume I had not observed, as it was also concealed beneath drawings. The binding was expensive morocco leather, dyed a rich Tyrian purple.

“Archimedes authored a treatise known as

On Spirals

,” Leonardo said as he opened the volume and began to turn the yellowed old parchment

leaves. The text was Greek, copied in a fine hand. But Leonardo soon paused where another hand, equally fastidious, had written in the margin, in Latin, with a different nib and slightly darker ink.

“Read it,” the maestro instructed me, as if I were an apprentice in this shop.

I did so, aloud, offering my own translation into Tuscan:

If a straight line, one end being fixed, is made to revolve at a uniform rate on a plane until it returns to its starting position, and if, at the same time as this straight line revolves, a point moves at uniform rate along this straight line, starting from the fixed end, that point will describe a spiral in a plane

.

My bewildered expression prompted Leonardo to add, “I will demonstrate.” Here he returned to his box with the platter on top, at which point I observed that this perfectly round wooden plate was in fact covered with a thin layer of wax. Leonardo employed his right hand to very slowly but smoothly turn the crank, so that the wooden wheel spun with no variation in its speed. With his left hand the maestro produced a silver stylus such as draftsmen use, placing it at the center of the wheel; as it turned, he slowly drew the stylus in a perfectly straight motion toward the outer edge. The effect of this motion, combined with the revolving wheel, was to inscribe a remarkably uniform spiral in the wax.

“I have created an Archimedes spiral,” Leonardo said, returning to his bound treatise. “This construction provided Archimedes with important proofs. Proofs that cannot be understood without his definitions.” He began to read, offering his own translation. “ ‘Let the length which the point that moves along the straight line describes in one revolution be the

first distance

.’ ” The maestro plucked up one of his notebooks and a piece of chalk. He began drawing from a central point in the page, making a line that wound around like the spiral he had made on the wax platter—except that he stopped when he had gone only one revolution around that center point. Without the aid of a measuring stick or straightedge, he drew a perfectly straight line from that center point to where the spiral had completed its first revolution.

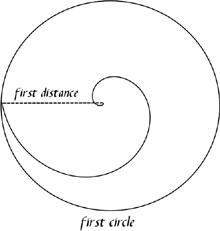

Turning to another page of the treatise, Leonardo once again drew in his notebook. He did not require a compass calipers to make an almost perfect circle, using the line he had previously drawn as the radius of this circle. “And here Archimedes tells us, ‘Let the circle drawn with the origin of the spiral as its center and the first distance as its radius be called the

first circle

.’ ”

“The square is the first circle,” I said, reciting the inscription on the

bollettino

he had shown me a few days before. The hair rose at my neck. “What in the name of God and Mankind …”

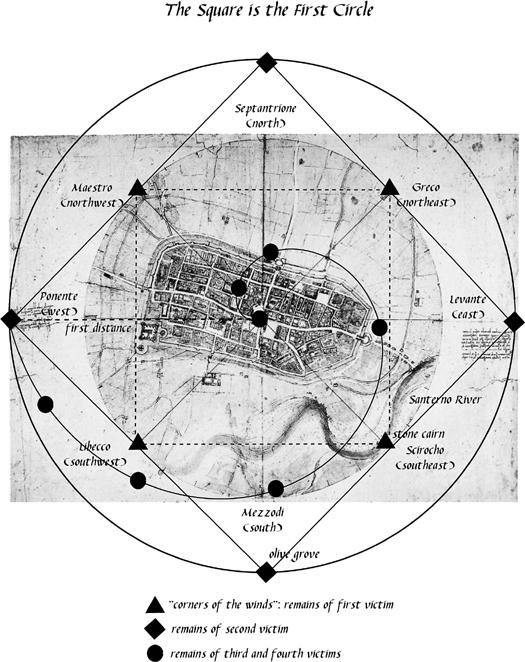

Leonardo had already produced his

mappa

of Imola; with none of his customary dithering, he placed atop it the tracing he had previously shown me in Imola, demonstrating the figure of a circle within a square. But now he placed above this another tracing tissue of the

same size, smoothing it into place, so that I could see well enough the geometric figures drawn upon it.

Leonardo had proved himself a better prophet than I. Because this was no mere

disegno

.

This was the Devil’s map of evil.

The topmost of the two tracings Leonardo had placed upon his

mappa

was similar to one I had seen in his studio more than two weeks previously—which on that occasion he had, in his frustration, covered with beans. The beans were now absent, so that I could again see the points where the cruelly butchered pieces of the two bodies had been found. Although the arrangement of these points had appeared entirely haphazard on my prior viewing, now they were connected by a line that looked as if it had been traced around a nautilus shell—or, to be more precise, represented the first revolution of an Archimedes spiral. Around this, the maestro had drawn the “first circle” with that “first distance” as its radius.

But that spiral was not even the most astonishing feature of this new construction. Leonardo had also indicated the four compass points where the first dreadful set of quarters had been found, and he had drawn the circle on which these points lay—the same circle that circumscribed the city of Imola on his original map. In addition, he had shown the four points that marked the location of the second set of butchered quarters, and he had drawn the square into which that inner circle had been so tightly fitted. This square, in turn, was just as tightly inscribed within the “first circle” defined by the first revolution of the spiral. Circle, square, then circle, all perfectly fitted, one within the other.

“You were correct, Maestro,” I conceded. “It is all of a piece. He did not indiscriminately discard the remains of his last victims, as I so incorrectly assumed. He has completed his

disegno

with the most terrible and marvelous of all his geometric figures.”

Leonardo took no satisfaction in this victory. His face sagged, a hand greater than his making a portrait of his weary soul. “I wish only to seek the True Light,” he whispered. “This

disegno

is intended

to impugn me and destroy everything the duke and I intend to build.”