The Mammoth Book of the West (2 page)

Read The Mammoth Book of the West Online

Authors: Jon E. Lewis

It could only happen in the West, that place of nobility and endless possibilities, cruel violence and depredation.

This book was born in the late 1960s when, sprawled on the floor in my grandparents’ house in the country, I used to watch

The Virginian

on television. Afterwards, I would go to my bedroom and peep out at the darkening land.

With just a touch of childish imagination, the fields below the window would be transformed into open range, the gently lowing Herefords into wiry Texan Longhorns. And then, over the far horizon would come a whooping band of Sioux braves, or a party of rustlers, or a no-good gunfighter.

The Virginian

not only hooked me on Westerns; it stimulated an interest in the real West which has never left me. That interest has been abetted by many people over the years and thanks are due to them, as well as to those who helped directly in the preparation of this book. I especially thank my grandfather, Joe Amos, who made me my first bow and arrow and my grandmother, Margaret Amos, who taught me to smell for rain on the wind. My gratitude is also extended to Eric and Joyce Lewis, Kathleen and Bill Ashman, Joan Stempel, Kathryn and Richard Cureton, the Jordan Gallery in Cody, Wyoming, Maria Lexton, Marge and Gene Ensor, Tony Williams and Kathleen Ensor Williams, Phil Lucas, Joe Turner and Michele Lowe, John Powell, Julian Alexander, Nick Robinson, Mark Crean, Jan Chamier, Dinah Glasier, and Eryl Humphrey Jones. Special thanks are due to copy-editor Margaret Aherne for her patience and skill. As ever, my biggest thanks go to my wife, Penny Stempel, who is beyond praise.

For Penny and Tristram Lewis-Stempel – Happy trails to you

To mount a horse and gallop over prairies, completely losing one’s self in vast and illimitable space, as silent as lonely, is to leave every petty care. In these grand wastes, one is truly alone with God. Oh, how I love the West!

Part I

The Way West

1. The Exploration of the West

1. The Exploration of the WestPrologue

They came, the first inhabitants of the New World, in small family groups, pushing eastward over the land bridge from Siberian Asia. They sought neither God nor gold but game, in the vast archaic shapes of the mammoth and the mastodon. No one knows for certain when the feet of these nomadic hunters first touched the soil of what would become America; it was some time towards the end of the Ice Age, not before 30,000

BC

but not later than 28,000

BC

. From Alaska, they fanned out across the northern continent, and then down through the central isthmus to the south. They remained hunters until the mammoth and mastodons were all gone, after which they began to adopt ways of living suitable to the lands into which they had walked. Some who had reached the Southwest, turned to agriculture and built magnificent stone cities. The people of the plains continued to hunt smaller game, especially a sub-species of bison,

Bos bison americanus

, the million-strong herds of which blackened the landscape. Around the Great Lakes, wild rice gathered by women poling bark canoes was the main means of sustaining the life of the people. Geronimo, the wild Apache warrior, looking back on his homeland from exile, would express the Indians’ beautiful adaptation to the land thus:

For each tribe of men Usen [God] created He also made a home. In the land for any particular tribe He placed whatever would be best for the welfare of that tribe.

With the diversifying of lifestyle, came other changes, of language, culture, even physique. Over time, the people no longer thought of themselves as a single entity but as many differing tribes – Dakota, Mandan, Seminole, Pequot, Pawnee, Kickapoo, Comanche and nearly 500 others, most of whose tongues were incomprehensible to each other, and some of whom were incessantly warring rivals. (The West never was Arcadia, despite its siren beauty.) The original inhabitants of America, though, retained one common belief wherever they went, whomever they became. They believed that the land belonged to no one. Tribes might fight over hunting grounds, but they had no concept of private property. The land was sacred, to be handed on almost untouched. As an Omaha warrior’s song expressed it:

I shall vanish and be no more,

But the land over which I now roam,

Shall remain,

And change not.

The great ceremonial song of the Navajo, “The Blessing Way”, contained a similar sentiment:

All my surroundings are blessed as I found it,

I found it.

And the aboriginal was bound to the earth by a mystical union. It was part of his body. When it was cut, he wept. The attitude of the European intruder was very different.

The first White to “discover” the New World is usually

held to be Christopher Columbus, who reached the Bahamas on 12 October

AD

1492. Believing he had reached an outpost of India, he christened the people he found on the island of San Salvador

Indios

. “So tractable, so peaceable, are these people,” Columbus wrote to his patrons, the King and Queen of Spain, “that I swear to your Majesties there is not in the world a better nation . . . and although it is true that they are naked, yet their manners are decorous and praiseworthy.” Where Columbus had sailed, other Spanish subjects soon followed. Led by the conquistadors, merciless hard-fighting minor noblemen, the Spanish overran the Caribbean and moved remorselessly westwards, lured ever on by the prospect of gold. In 1513 Juan Ponce de Leon landed on the American mainland. He found no gold, only flora. His men duly named the place

Florida

(“full of flowers”). Another conquistador, Panfilo de Narvaez, decided that Florida, its lack of yellow metal notwithstanding, was ideal for colonization. The attempt proved disastrous. But it accidentally resulted in the first sighting by White eyes of the American West.

Fleeing Florida in the summer of 1528 for the sanctuary of recently settled Mexico, the makeshift craft of Narvaez’s men was blown ashore on the Texas coast, near the mouth of the Sabine. Four Spaniards, led by Cabeza de Vaca and including the Black Moorish servant Estevan, survived shipwreck, disease, starvation, and enslavement by hostile Indians to reach Mexico on foot in 1536. Their saviour was Estevan. It was he who did the work, took the risks. As de Vaca later acknowledged, Estevan “talked to them [the Indians] . . . he inquired the road we should follow in the villages, in short, all the information we wished to know.”

De Vaca’s lost men could provide little cartographical information, but their tale prompted more purposeful

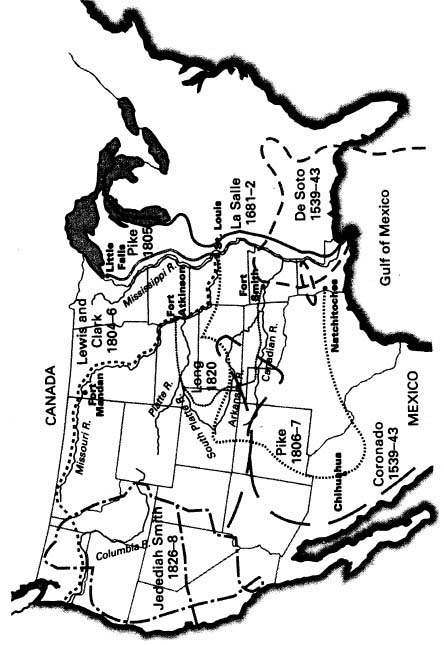

Spanish expeditions. In 1539 Don Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, the 31-year-old governor of New Spain, headed a great expedition which sought the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola, whose streets were reputedly paved with gold. From Mexico, Coronado marched northwards. Arriving in the land of the Zunis, who were astonished by the expedition’s horses (a mammalian form absent from the Americas’ indigenous fauna), Coronado demanded obedience to the rule of Spain. The ancient Zunis pelted him with stones, but then withered before the fire from modern Spanish arms. Disappointed at the Zunis’ lack of precious metal, Coronado set off for another fabled golden land, Quivira. Eventually, he penetrated as far north as present-day Kansas. Meanwhile, a rival Spanish party under the leadership of Hernando de Soto landed in Florida and stumbled westwards, fighting repeated skirmishes with Indians, eventually reaching Arkansas. In 1542 de Soto “took to his pallet” and died. He was buried in the great river he had found: the Mississippi.

By now, there were White men from other European nations probing the new continent. John Cabot sailed from England along the Atlantic coast of the continent in 1497. Portugal’s Gaspar Corte-Real reached Newfoundland and Labrador in 1500. Twenty-four years later the French-sponsored Florentine Giovanni da Verrazano entered New York harbour. In 1534 the intrepid Breton navigator Jacques Cartier explored the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. The response of the Spanish to this trespassing on their Forbidden Empire was to send a host of robed friars to America to establish missions and save the souls of the heathens (and surreptitiously pave the way for the later rule of Spain). In 1598 missionaries and settlers led by Juan de Onate founded the dried mud village of San Juan in the Rio Grande Valley, in what is now New Mexico. It was the first permanent European settlement in the American West.

More missions followed, in Arizona, Texas and California. Resistance by the aboriginals of the Pueblos (stone villages) to the word of God was met by military force and forced conversion. When the Acoma Indians of Sky City refused Spanish food requisitions, Onate sent an armed detachment which slaughtered 800 adult Acomans. Surviving males over the age of 25 had a foot severed, to make them living reminders of the folly of resistance. They were then herded into slavery.

Although the Spanish were the first to settle in the American West, ultimately its conquest lay with others. The great Pueblo uprising of 1680, which drove 2,500 Spanish from their homes and ranches, badly shook the Empire’s frontiering will. And Spain was too riven by internal difficulties and too interested in skimming off the surface wealth of the Americas, gold, to develop a coherent colonization policy. France, too, tended to view the New World merely as a place to plunder, whether for gold, beaver furs or Newfoundland cod. As a result, the whole of the Eastern seaboard from Canada down to Florida – a temperate terrain highly suited to large-scale agricultural settlement – was left unclaimed.

It was the fortune and fate of Britain that when she came to build an empire, this rich land remained free. The first British expeditions failed, but in 1606 the London Company was granted the right by James I “to deduce a colony of sundry of our people” in America, north of the 34th parallel. Three ships made their way across the ocean in 1607. “The six and twentieth day of April about foure a clocke in the morning,” wrote Master George Percy, “wee descried the Land of Virginia . . . faire meddowes and goodly tall trees, with such Fresh-waters runninge through the woods as I was almost ravished at the first Sight thereof.” After landing, the settlers built a village,

Jamestown, named in honour of the monarch. They were attacked by tidewater Indians and suffered a “Starving Time” (until the selfsame Indians brought them gifts of food), but they endured to become the first permanent British settlement in America. A timorous alliance with the Indian was even formed with the marriage of the Indian princess Pocahontas to the Englishman John Rolfe.

More British immigrants arrived; settlements and farms spread along the James River, and then to Maryland and the Carolinas. In 1620 a group of religious dissenters, the Pilgrims, landed in New England after their vessel

Mayflower

was blown off its course for Virginia. They decided to build their homes at Plymouth, where luck had washed them up. A decade later came the great 25,000-strong Puritan migration to Massachusetts. The European population of America grew inexorably – just as its native population declined inexorably. The White man’s microbes (particularly smallpox) devastated up to 90 per cent of some of the Eastern Algonquin tribes. Some Indians tried to make a stand against the disease-carrying invader, with his insatiable hunger for land. The Wampanoags of Native American King Philip killed some 600 New Englanders in 1675. But still the Europeans came. The only result for the Wampanoags was slaughter and slavery.

Soon, stable British colonies stretched along the Atlantic seaboard from New Hampshire to Georgia (and included New York and New Jersey, seized from the Dutch). The coastal strip became used up, overcrowded. The colonialists needed more land. The Virginians needed it for their tobacco boom crop (for a while even the streets of Jamestown had been turned over to the cultivation of the “weed”), and the agriculturalists of New England needed it for their farms. There was only one way the territorial

expansion of the British colonies could proceed – westwards, into the unmapped, unknown hinterland. It was now that the story of the West, of the frontier, really began.

In the beginning the West was in the East. It was the unknown and magic forest land which lay beyond the cultivated fields of the tidewater colonialists and stretched away to the forbidding ridges of the Appalachians, which walled the coastal plain.

Not that it was unknown for long. There was no hill that land speculators or trappers, with profit before their eyes, could not climb or woods that farmers could not clear. In 1650, only 43 years after the founding of Jamestown, Captain Abraham Wood led a five-day expedition through the “wilderness” as far as the Roanoke Valley in search of real estate for future resale. Also of the mind to make money from land speculation was Virginia’s governor, Sir William Berkeley, who organized an expedition in 1670 to discover a pass through the Appalachians themselves. The expedition was led by John Lederer, a German physician of courage and sensitivity. Lederer found himself overwhelmed by the beauty of the Blue Ridges. He did not find a way through. Thomas Batts and Robert Fallam did, in 1671, by following the Staunton River. They emerged into the Great Appalachian Valley, which runs from south of the Carolinas to northern New York, a place of almost Edenic character and fertility.