The Man Game (15 page)

With Toronto in the back, she canoed home to Sammy, who was waiting in the living room in a chair he'd soiled. She ran to him with desperate apologies. Sammy was calm and graceful. It was one of those things.

They made their way back through the woods to their hideout, to the dwindling stack of firewood, the leak in the roof, the faulty cookstove, and to the woeful Mrs. Litz, who was cloistered there for her own safety on this tiny nook of land caged in on all sides by acres of gnarled blackberry thistle, with nothing to do with her time but go absolutely skookum. On their way back to this grim nest, they discussed Mrs. Erwagen's proposition.

I never did go in for music halls, said Pisk at a whisper. So maybe I get her idea. Damn, Litz, what are we thinking here? Are you sure we should go with this lady?

What a we got to lose?

Try making our living off something doesn't exist except in her mind? The more I think aboot it, the more I don't know, eh â¦

Don't split hairs, said Litz at low volume.

Split hairs? Well, Iâ

And before Pisk could interrupt further, Litz added: You know this is our answer.

How do I know that?

Because, don't you want to be good at something for once?

We're good loggers.

No, I mean something people care aboot. No one cares when a logger's gone. We're no more important to businessmen than a piece a blotting paper.

They crawled through the long narrow passageway under the blackberry bramble and finally arrived at what had

become their home. It looked like a pile of sticks, a giant beaver dam hugging the titanic pillar that was an old dead cedar tree in the middle of harsh forest. Mrs. Litz was outside, waiting for them, hands on her little hips, her sloe-eyed expression one of deep despair, almost madness. For such a small pretty creature, she had a great set of lungs. After they swallowed their pride and listened to every last one of Mrs. Litz's complaints and demands, they ate dinner. Litz tried to make it up to her with gentle, obsequious noises by which he meant to compliment her cooking. They ate mutton and potato stew using the wooden spoons she'd carved. After they were done, he tried to touch her smooth soft cheek but she recoiled as if frightened that his thick fingers might cut her. It won't be much longer, Litz promised her, pretty soon we'll have it all taken care a, and we can go back to living normal. But she didn't want to wait any longer. She was all alone out here.

For a while the married couple argued while Pisk sat on his chair and smoked tobacco. By the end of the conversation Mrs. Litz was drunk and crying, and then she fell asleep. Litz looked at Pisk and without a word the two of them went back outside to chop firewood and wash up in the creek.

What choices do men got around here for some entertainment? Litz said as he cleaved the firewood in half and threw all the shivers aside. If a man wants to watch a fight, and we know he's up for that, then he's just as soon to watch this. That's all we need around here, Pisk.

I'm listening, said Pisk, rubbing the garments up and down a soapy washboard next to the creek.

In Chinatown it's checkers or dominoes and those lotteries. Them Chinee, they spend a lot a money on that. Men are so bored they play cards all day. You seen men around here bet on fist fights. Stand a good chance they bet on this idea. Everybody around here is bored to death. They gamble and drink and fight. What else is there to do when work is scarce?

Pisk hung their clothes on the line to dry and went over to help Litz stack the firewood. There's nothing out here for us

anymore, Litz said. What I suppose I learned because a our exile is there never

was

nothing for us here. The only thing anyone ever goes and does in Vancouver is drink and fuck away their fortunes. None a these men have futures. Pisk, man, I want a future. I was raised to be nobody. But I don't want to end up some bohunk like ol' Clough, drinking himself to death. We're all killing ourselves out here, for what?

Pisk stopped before throwing a log and considered what Litz said.

I don't want to die a boredom. Already we smoke too much a the opium, hashish, and drink our faces off. I don't want to lose my soul to that neither. I don't want to die in this forest worth less than what I came into the world with, said Litz. There's got to be more to life than being a handlogger.

Who do you think you are, Litz? You're nothing special. You and me both, we're just bohunks.

Not me.

Ah, said Pisk. You're just in love again.

Who, with Molly?

That's right, Molly. Exactly Molly. Good guess, partner. But listen, you don't have to love every ee-na just because you want to get some of it.

Look, said Litz. If you want to horse around, fine. Me, I'm ready for a betterâmore good from life. I'm not interested in anyone but my wife. You can see that Molly's got plans. We need something. We're prisoners right now. We need to do something, not just the same thing, eh? Or we'll never get ourselves out a this situation. You and me are different from the rest. We always set apace ahead. Let's do this.

Pisk heard what he was saying. They went back inside, stoked the fire, and lay in bed with Mrs. Litz. As they quarrelled over the blanket, she, between them, angrily, did not stir. They lay there on the mattress, with a myth on the brink of conception floating around in the men's heads, keeping them awake while Mrs. Litz dreamed. Without knowing what Molly intended, what she had planned, how could they know anything except their instincts?

Angry to be alive. Minna and I saw how the game was played. We saw the crowd it generated. The whole ordeal, event, continued to make me feel uncomfortable. It seemed that the least dangerous people in the yard that day were the sportsmen. The rest were good for fuck-all. All their money went to rims. All their dreams went to coastlines. All their time went straight to the streets. Angry to be alive, angry enough to kill.

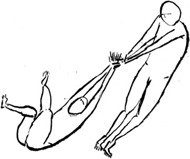

Every time something awesome happened on the lawn, a perfectly executed Medical Breakthrough for example

{see

fig. 4.1

}

, badly postured, spotty-eyed, omnivorous young men in the audience whelped and fisted the air with increasing hostility. Yeah, they announced from the lowest pits of their voices. Yeah, yeah, boo-yeah. Just standing next to one of them was too much for me. It was like standing next to the speakers at a rock show. From beneath their jerseys and slack belts and the silver crosses of no meaning that dangled there on long silver thread across their chests, an amplified bear howl escaped from every one of their hearts.

Motherfuck your dada, said one, handrolled grass pinched in his fingers. I'll fuckin' show your dada how to act, I'll stub him in the face with my stooge rocket.

FIGURE 4.1

The Medical Breakthrough

Calabi's commentary: A complete upheaval in the order a events in which any move is redirected using momentum to swing his opponent one complete rotation before releasing him.

Who are they talking to? I asked.

Apparently the men there, said Minna, nodding to our sportsmen.

I'll fucking tie your dada in a purple knot and Jack trip him, said a bleach-blond neckface.

I'll fuckin', I'll fuckin', I'll fuckinâ, said another, searching through his grey matter for a wizened slur. Nothing appeared.

Across their shaved heads lurched a series of fast shadows, ear to ear, as eastbound crows lured themselves to power stations for another night of anger. That pitiless catechism of crowsong, it echoed in the altitude, it kept the neighbours up. All crows are men.

Minna wasn't really my

girl

friend, but I loved her nonetheless for who she was and I accepted the awkward halted romance we had because it was better than nothing at all. I did feel frustrated and vulnerable. Mostly it was the fact of the nudity, the lack of it in our relationship and the proximity to it at this very moment.

Ken wormed his way into a handstanding bourée. Silas uprocked it. Now the game was more and less interesting

{see

fig. 4.2

}

. I was preoccupied with not becoming entangled in the moshing thrusts of the troublemakers and their allies.

FIGURE 4.2

The Boxing Chinee

Calabi's commentary: The skilled player uses his feet and knees as accurately as a lion tamer his whip and chair.

FIVE

FIVECome, then, soldiers, be our guests. My life was one of hardship and forced wandering like your own, till in this land at length fortune would have me rest. Through pain I've learned to comfort suffering men.

â

DIDO, VIRGIL, TRANS. R. FITZGERALD

Bud Hoss had gotten the job on the donkey engine by answering Furry & Daggett's note on the blackboard at the Sunnyside Hotel. There'd been all sorts of tough jobs chalked up. Doyle wanted a bucker for $1 a day; Rowling needed ten axemen for a slope in Langley; Furry & Daggett were hiring rigging slingers for $1 to help clear a giant job and were looking for a guy who knew how to do a controlled burn. That was a specialty of Hoss'sâfires, that is. He'd never lost control of one. A man who worked the donkey engine gathered up debris and set it ablaze, a means of getting rid. Easy enough work on a rainy day, and there were lots of those, but rather more dangerous business on a dry hot windy summer afternoon, as Vancouver well knows.