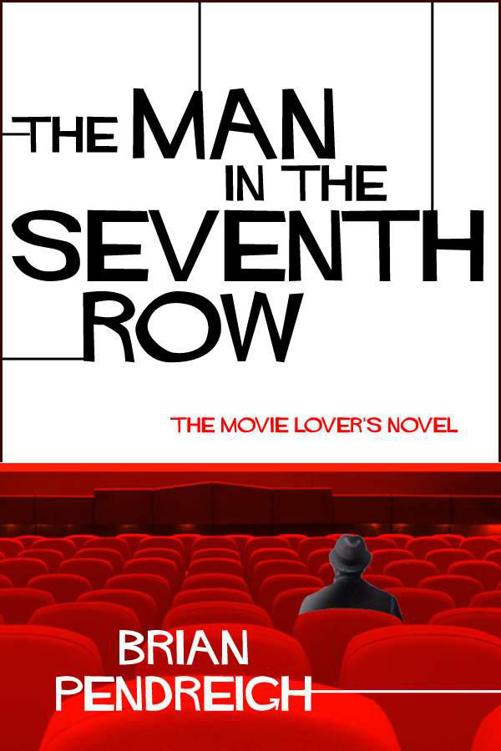

The Man In The Seventh Row

THE MAN IN THE SEVENTH ROW

(or THE MOVIE LOVER'S NOVEL)

by

Brian Pendreigh

Published by Blasted Heath, 2011

copyright 2011 Brian Pendreigh

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission of the author.

Brian Pendreigh has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

All the characters in this book are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cover design by JT Lindroos

Cover photo: Ferenc Szelepcsenyi/Shutterstock.com

Visit Brian Pendreigh at:

ISBN (ePub): 978-1-908688-10-1

ISBN (Kindle): 978-1-908688-09-5

Version 2-1-3

Also by Brian Pendreigh

Non-fiction

The Pocket Scottish Movie Book

The Legend of the Planet of the Apes

The Scot Pack

Ewan McGregor

Mel Gibson And His Movies

On Location: The Film Fan's Guide to Britain and Ireland

The Best of the Scotsman (anthology)

The Scotsman Quiz Book (with Jim Brunton)

The Scottish Quizbook (with Jim Brunton)

Also by Blasted Heath

Dead Money

by Ray Banks

Phase Four

by Gary Carson

The Long Midnight of Barney Thomson

by Douglas Lindsay

All The Young Warriors

by Anthony Neil Smith

Keep informed of new releases by signing up to the

Blasted Heath newsletter

. We'll even send you a free book by way of thanks!

1

Scotland, June 1962

Memories are elusive and unreliable things. You think you have them, and then, suddenly, they are gone, like tears in the rain. And like tears in the rain, you can never be sure they were there in the first place.

He was not sure if he remembered, or if he simply thought he remembered, because his mother had told him so many times that that was the way it happened, a long time ago. Either way, whether it happened or not, he knew it was true.

***

North Berwick is a chilly seaside town on the Scottish coast. Every morning commuters drive the twenty miles to work in the banks and insurance offices of Edinburgh. It is now a dormitory town, but not so long ago it was a thriving holiday resort. When he was a boy, his family spent their summer holiday fortnight there.

He was about four when they took him to the Playhouse cinema for the first time. The little boy sat transfixed among the packed rows of adults as the house lights dimmed and music exploded in his ears. His vision and imagination were filled with moving pictures of men on horses. He was swallowed up by the adventure, the action, the strange, exotic people and places. It sucked him in and he was no longer aware of those around him. The people around him now were Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen and James Coburn, though he knew them, not by those names, but as Chris, Vin and Britt. He had entered another world, the alternative reality of the cinema.

He sat open-mouthed, without a whisper – so his mother would tell him in later years – until Yul Brynner took off his hat. Then he screamed out in shock and horror: '

Look!' A finger thrust towards the man in black. 'He's got ... no hair.'

Everyone seated around them laughed ... or maybe tutted.

For the rest of the fortnight the boy rode the sand dunes, clutching imaginary reins, slapping his thigh until the flesh reddened. Sometimes he would draw his pistol and shoot a Mexican bandit or six. At first the pistol too was imaginary, then his father bought him a silver-painted toy Colt 45, which he kept in immaculate condition for years.

As the years passed, his attitude towards bald people changed. By the time he was 17 he shaved his head, and wore only black shirts, as Brynner had done.

He remembers quite clearly seeing

The Magnificent Seven

as a small child. It is his favourite film. But it may simply be a romantic trick of memory that it was the first film he saw. The suggestion that he shouted out when he saw Brynner was bald may just be a fanciful notion. Surely it's obvious from the start that Brynner is bald?

As a man, he watched the film again and waited for Brynner to take off his hat. And he waited and waited. The audience learns a lot about Brynner in those opening scenes when he accepts the commission from the Mexican dirt farmers to defend their village and gathers his tiny force of mercenaries, adventurers and idealists. He is a man in total control. Everything he does is slow and deliberate. He never panics, no matter the odds against him. He never loses his temper, never rushes, hardly even breaks sweat. Which is probably why he doesn't need to take his hat off. We feel we know him, a role model, a hero, a comrade-in-arms, and yet he retains this incredible secret beneath his headgear.

Midway through the film Brynner is hard at work digging a trench beneath the burning Mexican sun when he finally removes his hat. And he does so only momentarily. Like Sharon Stone crossing her legs in

Basic Instinct

. But it is long enough for Brynner to reveal that, unlike Sharon Stone, he has no hair. It is easy to imagine that a small boy might be unable to control his reaction to such a revelation.

It is a slight, inconsequential story. But the boy's exclamation upon the revelation of Brynner's baldness may be the man's earliest memory. Maybe. Maybe not. Maybe it is someone else's memory. Maybe it never happened at all. He does not know.

The picture house is gone now. The actors are dead, but the film survives. And that is the main thing. When you watch a great film nothing else matters. The man knows that. He knows that audiences refused to leave their cinema seats during the Blitz, as London crumbled around them, and he knows how the people looked for sanctuary from the Great Depression in the spectacle and extravagance of Busby Berkeley's musicals. The movies were the great escape long before Steve McQueen made his bid for freedom. The man knows that.

2

Los Angeles, March 1996

Everything is dark. A beam of light cuts through the blackness. It originates high at the back of the hall, hovers above two dozen scattered, shadowy heads and terminates in an explosion of Sixties Technicolor, an alternative reality in which colours differ from those in our own world. A classic film is playing.

A middle-aged man in a neat moustache that seems to have survived from the previous decade, heavy black sunglasses, sky-blue shorts and matching open shirt, calls for attention from the guests spaced around the edge of the pool. With all the enthusiasm of a children's television presenter he bounces over to the patio door through which he asks if the feature attraction is ready. From behind the door, a nervous voice makes a mumbled appeal for further discussion.

The speaker remains unseen. But the audience know

s who it is. They know the film, scene by scene. They have all seen

The Graduate

. Everyone has seen

The Graduate

. It came out in 1967, plays like a favourite old Beatles 45 and there is a temptation, not always resisted, to whisper some of the choicer lines before the actors do.

There is a ripple of anticipation as the man with the moustache attempts to coax the feature attraction from his sanctuary into the Technicolor, Californian afternoon. Practising Kissenger's art of shuttle diplomacy, he bounces from patio door to poolside, promising the guests a practical demonstration of the exciting 21st birthday present that cost over two hundred bucks and that is currently being worn by his son Benjamin Braddock.

A man shuffles along the seventh row of the cinema and sits down without once looking away from the screen, a warm smile of recognition on his face.

The patio door is thrown open to reveal a figure in a black rubber wet suit and flippers. It is wearing an air tank on its back and carrying what would appear to be a harpoon in its right hand. Its features are obscured by a mask and mouthpiece, connected by pipe to the tank. It slowly, hesitantly makes its way forward across the kitchen floor, slapping each foot down with a sound reminiscent of a seal clapping for fish. And all the time Mr Braddock Senior burbles on like the ringmaster at the circus, 'perform ... spectacular ... amazing ... daring', as if he were indeed introducing a seal and might reward it with a halibut.

Through the mask we get the diver's/seal's perspective of proceedings: Mr Braddock clapping and waving his feature attraction towards the pool. His words remain silent. We hear only our own breathing from within the mask. It appears Mr Braddock may walk backwards right into the pool, but at the last moment he stands aside. The diver looks down into the clean, clear, sparkling blue of the Californian dream lifestyle and turns away. His father, wearing a sunhat at a jaunty angle, and his mother, sporting white-rimmed sunglasses and a huge, white-toothed laugh, shout soundlessly and gesture excitedly towards the water. It is like watching

The Muppets

with the sound turned down. Suddenly the diver drops into the pool. When he surfaces his two bespectacled parents are there to greet his return with their smiles as permanent as the breasts of an aging Hollywood starlet. It is the sort of touching family moment of which only cinema is capable, as Ben shares his isolation with the general public and yet remains alone behind his mask. He retreats again below the surface. He stands on the floor of the pool, holding his harpoon, like Neptune, his sub-aqua reign dictated only by the number of bubbles in the tank on his back. There are a lot of bubbles. He can outlast his parents. He can outlast their guests. He can outlast the director's patience. While the camera lingers on the defiant figure at the bottom of the pool, the dialogue of the next scene begins on the soundtrack.

The light from the screen illuminates an expression of doubt on the face of the man in the seventh row. He knows the dialogue like the lyrics of a song, but the singer seems to have rearranged the verses. Ben is expressing some concern about his future to his father. This should not be the next scene. Not in the standard version of the film. The man thought he had missed this bit. But these days no one seems content to consider a film complete. This is the era of the special edition and the director's cut. Give Kevin Costner an Oscar for

Dances with Wolves

and he will give you another hour of film. Give Ridley Scott cult status for

Blade Runner

and he will give you a unicorn and a whole new meaning; possibly. Give George Lucas some new electronic technology and he will remake

Star Wars

.

The man in the seventh row knows nothing of a new version of

The Graduate

. Maybe the cinema just got the reels in the wrong order. And yet something else is different: unfamiliar and yet familiar. And a shiver runs down his spine, just as it had the first time he saw

The 39 Steps

and Robert Donat explained to Godfrey Tearle that he did not know the identity of the villain but he did know that he had part of one finger missing. Tearle asks if it is this finger, and holds up his right hand to reveal a thumb, a forefinger, a middle finger, a ring finger and just half of a little finger. For a moment the man in the seventh row feels quite cold, as if Benjamin is holding up his hand to reveal it is not all there.

Ben's father's head partially obscures the audience's view of Ben. Ben's mother comes to encourage him to leave his room and meet their friends, including Mrs Robinson. Ben's mother walks directly in front of the camera, so the audience can see neither Ben nor his father.

Ben rises from his melancholy. He is neatly dressed in dark jacket, white shirt and yellow, red and black striped tie. A reassuringly conservative image of youth in a decade of revolution, just as the man remembers from previous viewings. The clothes are the same. The words are the same. The scene is the same, except for one small detail. Every other time that the man has watched

The Graduate

the character of Ben has been played by Dustin Hoffman. This time Dustin Hoffman is not Ben. Ben is being played by someone else. The man in the seventh row recognises the features at once, but there is no smile of recognition now.