The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit (15 page)

Read The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit Online

Authors: Lucette Lagnado

S

hortly before my sixth birthday, I developed a series of mysterious ailments that baffled the entire Cairo medical community.

It all began with a low-grade fever that refused to go away, along with a strange swelling in my thigh. My symptoms multiplied to include a rash, any number of aches and pains, and finally, an overwhelming sense of lethargy that seemed entirely at odds with the playful child I had been.

Friends and well-wishers inundated us with advice, from crude homemade remedies to the latest scientific therapies.

Mom's favorite seamstress prescribed a poultice that was to be applied on my leg at least once a night. Before I went to bed, a smelly concoction of warm dough, mustard, vinegar, and herbs was placed on me for an hour or two, or until I got too fidgety and yanked it off. A series of doctors descended on Malaka Nazli to administer injections, as well as prescribing an array of strange pills and potions. My sister Suzette, who dreamed of medical school but settled for a job teaching kindergarten at the Lycée Français de Bab-el-Louk, suggested

finding a top specialist, someone with offices

en ville

âpreferably a Europeanâas no one my parents had brought in met with her approval. Our Sudanese porter Abdo advised us simply to pray.

Nothing worked.

My father, by now a veteran of long, complicated ailments, decided to take matters into his own hands. Together, we made the rounds of Cairo's top physicians, going from one to the other, one to the other, in search of an answer to what ailed me. Most of the doctors had been treating him for years, and knew him on a first-name basis. Ever since his fall shortly after I was born, my father had endured recurrent, painful flare-ups of his hip and leg. He'd never had the broken pin removed, and he limped noticeably.

We made an odd pair as we toured the specialists' officesâa tall, distinguished silver-haired gentleman whose right leg dragged, walking hand in hand with a diminutive girl with long dark hair and dark eyes, who shuffled ever so slightly on her left leg.

My dad seemed at home with these elite physicians, whose offices were in the most upscale section of the city. Could you please examine my child? he asked each of them politely, almost obsequiously, as if they'd be doing him a favor by adding his slip of a daughter to their practice. As if he weren't going to reward them with wads of large bills from his wallet.

The Cairene medical establishment was frankly bewildered. The blood tests came back negative. X-rays taken of every part of my body revealed nothing out of the ordinary. The syrups and pills and injections seemed to have no lasting effect. The swelling in my leg refused to subside, my fever kept returning, and I had also developed a slight rash. I felt so tired that I didn't want to play anymore, save with Pouspous. One doctor after another was unable to say what was wrong, beyond insisting that whatever ailed me was undoubtedly benign.

At last, my sister located a physician known reverentially as “Le Professeur.” Suzette was certain the doctors my parents were consulting on my behalf were leading us down a primrose path. She was always at war with my father, persuaded he was letting me down, and my care had become the latest pretext for her rage.

Le Professeur was a man of such renown that few ever bothered to

use his name. He was revered by his patients, who included affluent Jews and Arabs, as well as whatever was left of the European community. His strange habit of always wearing white cotton glovesâto hide a skin condition, probably eczemaâonly added to his mystique, and to my fear of him.

After closely examining me, in particular, the lump, he ventured a diagnosis: I had contracted a case of Cat Scratch Fever,

la Maladie des Griffes du Chat.

My father, no stranger to medical jargon, looked startled at the improbable-sounding verdict. What on earth was the

Maladie des Griffes du Chat,

he asked, and why had it taken so long to figure out what was wrong with me?

The Professor grimly described an obscure disease, first isolated by a French scientist in the 1800s. Even now, he said, Cat Scratch Fever was known to only a handful of practitioners, and no doctors save the few who had studied in Paris and other great European medical centers were even vaguely familiar with the disease that was apparently attacking my entire immune system. The fever was thought to be caused by a scratch or bite from a cat that unleashed a painful inflammation of the lymph nodes. Children were the most vulnerable. No doubt, my cat had scratched me near my thigh, resulting in the unsightly cyst he called

un ganglion.

I didn't understand much of what the doctor saidâonly that he seemed to be blaming my illness on Pouspous, whom I held in my arms much of the day and who ate with us at our dining room table. How could my cherished calico be to blame for the injections and blood drawings and legions of men in white coats who were constantly poking me? The uncertainty, the fear, the possibility that I was dangerously illâit was all the cat's fault.

Having rendered a diagnosis, the Professor seemed far less certain of the cure. Cat Scratch Fever was still a medical mystery, he told us, and no one really understood it. While antibiotics were thought to help, there were no definitive remedies. The Professor could only express the hope that my Cat Scratch Fever would go away by itself.

Children, he told my father as he patted my head, can heal almost by magic. They can seem deathly ill and then, overnight, be well again.

“Dieu est grand,” my father exclaimed. He said that whenever he felt hopeful or frightened.

The Professor nodded in agreement, but as if to hedge his bets and ours, he made us an offer. If I came back to his office once or twice a month, he would monitor me and determine whether I was showing any signs of improvement. He attempted a smile my way. I didn't smile back; I kept looking at his white gloves.

They made me anxious; would he ever take them off?

Vowing to bring me back promptly in two weeks, my father took me by the hand and walked with me outside to the street where we hailed a taxi.

He reached into his pockets and pulled out several pieces of candy in pretty silver wrappers. “Loulou, prend,” he said, handing me some bonbons, my reward, I suppose, for having endured the Professor's relentless examination. My father never left the house without a supply of candy as well as the Lucky Strike cigarettes he kept in a silver case. Though he never lit up, he loved to give out the popular American cigarettes to friends and business associates.

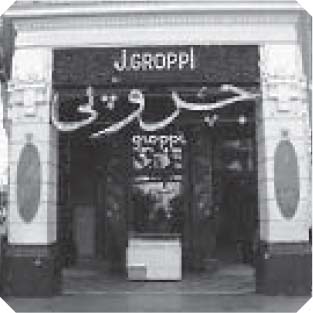

He asked the driver to take us to my favorite hangout in all of Cairo: Groppi's. It was a surefire way, he knew, to cheer me upâas simple as letting me order a cup of

pêche Melba.

Sitting there with Dad, amid the splendor of Groppi's pebbled garden, eating spoonful after spoonful of the delectable peach ice cream that came in a tall fluted glass, topped with whipped cream, I almost managed to forget the white-gloved doctor.

The legendary patisserie was struggling to survive in the postcolonial world, even as many of its clients left the country. It still maintained two locations, its grand flagship store on Suleiman Pasha, and the one I liked even more, on Adly Pasha, because it had outdoor tables set within a pebbled garden. This symbol of foreign decadence had managed to forge a peace with the new revolutionary rulers, and it was whispered that Nasser and Sadat stopped by on occasion, if discreetly. The remaining expatriate community, the smattering of Jews and French and Italians who had somehow hung on, kept Groppi's as their unofficial headquarters.

My father could tell that I hadn't liked the Professor, but he was still

in a cheerful mood. Merely having a name for what ailed me was progress. For so many months, my family had lived in a state of uncertainty, wondering what was wrong with me. I had even overheard my older sister use the word

tumor

to describe the lump that refused to go away.

Groppi's of Cairo.

I had no idea what a “tumor” was, but I guessed from the way Suzette said it that it was bad. Very bad.

When we came home, my mother rushed out to ask what the latest specialist had said. Almost immediately, the order came down: I was to stay as far away as possible from Pouspous. “Tout ça, c'est à cause du chat,” my mother said crossly; It's all because of the cat. At last she had an object for her rage, someone she could blame for my strange illness. I had the distinct sense that if she could, she'd simply boot out Pouspous and forbid me to ever play with her again. She did make me promise to stop embracing the cat or carrying her around in my arms, as I loved to do.

Â

I TURNED SIX IN

the fall of 1962, and my family was in the throes of deciding whether to abandon a country they loved deeply but which no longer wanted them, or whether to tempt fate as well as the authorities by trying to stay.

My father, who couldn't fathom life outside of Egypt, opted as always for holding on. His health was so fragile, he couldn't envision a lengthy voyage. Besides, his business was here. His synagogues were here. And though nearly every single member of his extended familyâbrothers and sisters, nephews and nieces and cousins too numerous to mentionâhad left, he still had friends and acquaintances in Cairo.

But it was getting harder and harder for Dad to resist the pressure: Jews were leaving in droves.

The convulsive departures were under way throughout the Middle East. Countries where Jews had lived harmoniously with their Arab neighbors for generations found their situations untenable. One after the other, Jewish communities in Libya, Algeria, Yemen, Iraq, Tunisia, Morocco, Lebanon, and, of course, Egypt dispersed. They left behind magnificent synagogues, schools, hospitals, and a way of life that had been, in many of these countries, often blissfully free of intolerance. World War II was fresh in everyone's mind, as were the mistakes the German and European Jews had made in staying where they weren't wanted. The world, still reckoning with the aftermath of the Holocaust, was determined not to risk another slaughter of Jews. Country after country opened its doors, and from the late 1940s through the early 1960s, nearly one million Oriental Jews scattered to the four winds. They left for Israel and America, as well as fanning out to Italy, England, Spain, France, even Australia and distant corners of Latin America.

Alas, what no one could stop was the cultural Holocaustâthe hundreds of synagogues shuttered for lack of attendance, the cemeteries looted of their headstones, the flourishing, Jewish-owned shops abandoned by their owners, the schools suddenly bereft of any students.

We were witnessing the end of a way of life that many would look back on with a mixture of bitterness and longing.

Some, like Dad, tried to stay put, unable to accept the finality of the situation.

Our lives seemed to go on as before, but beneath the veneer of normalcy there was a feverish uncertainty. We didn't know whether we'd be around another month or another year or another ten years. I was supposed to start second grade at the Lycée Français de Bab-el-Louk, but my father still hadn't paid the tuition. It wasn't that he couldn't afford it. He still had means to pay for the best doctors, the best restaurants, and the best schools for his children. But it was such a tenuous time, and he was feeling squeezed by the Nasser regime. Most painful to my father was the evisceration of his beloved stock market. Nasser had nationalized one company after another, which made many of Dad's holdings worthless.

“On a tout perduâon n'a plus rien,” he told my mother one afternoon; We have lost everythingâwe have nothing left. He was close to tears, especially since my mom had always disapproved of his passion for investing, and had felt that stocks were a risky proposition. Tears were very unusual for my father. My sister Suzette had a twenty-pound note on her; she went over and offered it to him. He refused.

But he held off paying my tuition: did it make sense for me to begin a school year I might not be able to finish? As a result, the headmistress, quite sensibly, wouldn't let me enroll. This distressed my mom to no end. Without telling Dad, my mother took me across the street for an interview at the Convent of the Sacred Hearts. One of the most respected schools in all of Egypt, it had, on occasion, admitted Jews, including my older sister.

When my father found out what she had done, he was furious. He had always felt Sacred Hearts paved the way for Suzette's rebellion; he wasn't taking chances with me.

“Jamais de la vie,” he said. Never.

But my mother, who rarely asserted herself, was adamant. If Sacred Hearts was out of the question, then he would have to go at onceâat onceâto the Lycée Français and settle the debt to allow me to attend classes with the other children. The next day, I found myself once again enrolled at the Lycée de Bab-el-Louk, walking round and round the vast courtyard with my friends.

My illness became a diversion from the larger pressures we faced. The burden of caring for a sick child and an ailing, much older husband, combined with the need to make a firm decision about whether and when to leave, was taking its toll on my mother. She was teary-eyed and fretful, wondering what would become of us, most especially “pauvre Loulou.” Since the onset of the fever, that is all she ever called me.