The Man Who Saw a Ghost: The Life and Work of Henry Fonda (6 page)

Read The Man Who Saw a Ghost: The Life and Work of Henry Fonda Online

Authors: Devin McKinney

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Actors & Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Movies, #Biographies, #Reference, #Actors & Actresses

Little Theatre was a middle-class phenomenon with progressive intentions and a conservative agenda. “Like other reform activities in the era,” Chansky writes, it “had contradictory strains; it included forward-looking activism and modernist aesthetics as well as skepticism, nativism, elitism, and nostalgia, sometimes within the same production company or publication.” Certainly the movement took for granted the cultural supremacy of those who drove and financed it: “Most Little Theatre workers assumed that their middle-class, Protestant heritage was a standard by which all culture could be measured.”

But in the context of middle-class, suburban Omaha in the 1920s, the Community Playhouse does not do badly. Under Foley, it cops to light Broadway fare but also stages naturalism, futurism, high farce—Shaw, Wilde, Molnár, O’Neill, Capek. Audiences are kept alive to past classics and modern currents, and the ideological limitations of Little Theatre are perhaps pushed out a few inches. The contradictions noted by Chansky provide the ideal opening into acting for a young man whose exteriors and values are conventional but whose ambitions and perceptions are extraordinary. Little Theatre allows Henry Fonda to experiment with states of safety and expressiveness, diverting him from aimlessness and the Omaha blues while giving him access to another world—that torturing, tantalizing state of watching and being watched.

The key turns in the fall of 1926, when Henry plays the lead in

Merton of the Movies

, a George S. Kaufman–Marc Connelly comedy about a Middle Westerner who stumbles into Hollywood stardom. Omaha’s theatergoers give Henry a standing ovation, and later, in the Fonda parlor, the family eagerly dissect the show: Henry, mother Herberta, sisters Harriet and Jayne—all but William, who has been skeptical of his son’s stage ambitions from the first, and who, at this moment of triumph, hides himself behind a newspaper.

Feminine praise pours over Prince Henry, while the elder remains hidden, judging all by his silence. Then a sister begins to speak in merest mitigation of the praise, suggesting how Henry might better have crafted his performance this way or that.

“Shut up,” the father says. “He was perfect.”

And just that fast, he is back behind the newspaper.

Henry’s life is decided that night. In quick order, bourgeois distractions will be traded for a new mode of existence, one that for several years will be all rail and no station, all fall and no net. In a few months, he will quit the credit office and become Foley’s assistant director at the Community Playhouse.

First, though, he will hit the road with a hard-drinking Abe Lincoln impersonator, playing to farm families along the heartland circuit.

Beyond that waits the itinerant life of an unemployed actor in hungry days. Soon Henry will be toiling in repertory up and down the coasts of New England; living on rice in a Manhattan garret; pioneering a course eastward, whence the Fondas had first come. Tracking the elephant, the black dog at his side.

* * *

As he moves, Fonda keeps an eye on the terrain—observes his fellow citizens, judges and sometimes condemns them. But because he has the “appearance of sincerity,” he is accepted; and because he has more than that, he is admired, elevated.

He represents our best ideals. He also represents much that we do not like to talk about. Fonda breaks with the mass of Americans on a basic point: He has a compulsion toward remembrance. Not nostalgia, but recall—true, deep, and clear. It’s this that makes him a critic at the same time he is leader and representative. As a nation, we seldom allow ourselves to remember too vividly the bad we’ve done. Yet always Fonda seems to ask: What does it mean to remember it as it happened, to remember it all?

It’s an eminently American quality to live as if history didn’t exist. We’re encouraged, by our cultural heritage as much as our leaders, to forget the past. But Henry Fonda acts as if he has never forgotten anything.

3

A Time of Living Violently

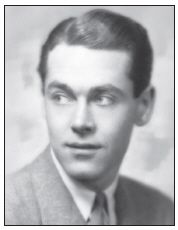

Fonda’s first head shot

The Henry Fonda who left Omaha was raw youth, an actor with ambition but without a persona, willing to hurl himself at any challenge. He was a leaper, a laugher, a fighter; he played characters with exotic accents; he sang, danced, walked on his hands. There was nothing his arms and legs, face and voice wouldn’t try.

As a lover, too, he was eager for all-or-nothing bets. So he fell for another actor, a starlet of imperial breeding, impossible demands, and unstoppable talent. When it came crashing down, the noise stunned the boy into silence. He drew back, guarded his obsessions and fears, and began vouchsafing his talent through an opening that, for both good and bad, could seem the narrowest point of emotional entry a screen star ever presented to an audience.

Fonda knew disillusion long before the audience’s eyes met him in

The Farmer Takes a Wife.

He was experienced in varieties of loss. That—and the inborn Nebraska austerity—must be why, from the start, he made such a grave impression; why he had a rare feel for anger and sadness; and why, at the other end of things, he could seem closed off, unreachable, an enemy of feeling.

* * *

Wearing a Union army uniform, slick hair sliced in the center, young Henry squints into the sun. Hands clutched at his back, he embodies the military posture of Maj. John Hay, presidential secretary. Beside him, much taller, wrapped in a shawl and black raiment, eyes shaded by a stovepipe hat, is the Lincoln impersonator, George Billings.

A crack runs through the photograph like a vein in old skin, a score in marble, a divide in time. It’s the spring of 1926. At one hundred dollars a week, Fonda has been hired by Billings—once a Hollywood carpenter, now the star of a silent film called

The Dramatic Life of Abraham Lincoln

—to write a show-length sketch out of famed Lincoln speeches. Additionally, Henry is to act the part of Major Hay, which mainly requires his paying rapt attention to the great man’s orations.

Billings and Fonda ride the circuit of little theaters and picture palaces across Nebraska, Iowa, and Illinois. Thanks to the intensity of the star’s portrayal, they are a success. “Lincoln of Stage Sinks All of Self in Soul He Plays,” reads the

Evening Courier

of Waterloo, Iowa, where they play the Strand Theater. “I pride myself that when I am acting, no one can see Billings,” the star says, using words Fonda will paraphrase many times in the course of his own career. “The audience … see only the character I am living for that moment.”

A scene from the show is described. Major Hay tenders Lincoln the death warrant of a Union soldier prosecuted for desertion. Hay then reads a letter from the man’s wife, explaining that she had called her husband away “in a time of great need” and pleading with Lincoln to spare his life. “As the long-fingered hands gripped the death warrant and tore it in two and two again,” the witness records, “many eyes watching Lincoln were wet with tears. And Lincoln’s own eyes streamed tears into the shawl.”

George Billings is a drinker. Some nights he fails to appear, and Fonda is onstage alone, gamely reading Lincoln’s letters. Finally, after one such night, Henry leaves the theater and doesn’t return.

But picture him sitting at the side of the stage, witnessing, as Billings declaims the second inaugural address: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right…” At the exact melodramatic point, the theater’s modest orchestra keens the melody of “Hearts and Flowers.” And Fonda watches this aged woodworker, drunkard, and ham actor believe in himself, in Lincoln, perhaps even in the promise of his country.

Maybe that is how it went, nights when George Billings’s eyes “streamed tears into the shawl.” Those who would know are long dead now.

* * *

The prairie road offers no spectacle, and meager reward. So you leave. You dream of elsewhere: New York City, cradle of the real American theater.

Henry gets his first taste of it in the early spring of 1927. An Omaha woman asks if Henry might travel to Princeton, New Jersey, and drive back with her son, who has purchased a new Packard. Henry grabs the chance and practically lives for a week on Theatre Row. He sees, by his account, such eminences as Helen Hayes in

Coquette,

Otis Skinner in

The Front Page,

Ethel Barrymore in

The Constant Wife,

Charles Bickford in

Gods of the Lightning,

Glenn Hunter in

Tommy,

and Humphrey Bogart in

Saturday’s Children

.

*

From this trip comes an anecdote so unlikely, it stands a chance of being true. Henry double-dates with his friend and two sisters named Bobbi and Bette. Sitting in the twilight behind Princeton Stadium, he plants a nervous peck on his debutante—seventeen-year-old Bette Davis, who notifies Henry the next day that her mother will soon announce her daughter’s engagement to the young man from Omaha. Gasping, Henry flees the scene—only to bump into Davis a decade later, by which point she is an Oscar winner and they are costars in a comedy called

That Certain Woman.

The trip east is a head spinner. In a week, Henry has discovered Manhattan, Broadway, and the desire of a wealthy, sophisticated young woman. Each is a net that catches him forever.

After that, Omaha must seem a gentle suffocation. Fonda accepts Gregory Foley’s offer of an assistant directorship at the Community Playhouse, and in the next year he squeezes all opportunity out of it. He acts in productions of

The Potters, Secrets, The School for Scandal, The Enemy, Rip Van Winkle, Seventeen,

and, opposite Do Brando, O’Neill’s

Beyond the Horizon.

He is biding his time, keeping the stage beneath his feet and the fantasy alive.

* * *

Nineteen twenty-eight is the summer of his leaving. With a family friend, he drives east to the gnarled arm of Cape Cod. He’s heard of the summer-stock theaters that dot the island, servicing the entertainment needs of weekend commuters, maiden aunts, antique dealers, and sailors on liberty. The Cape is an outpost of Little Theatrism, and in the late 1920s, idealistic Ivy League drama graduates are as common as sand crabs on the beaches.

Henry auditions first at the Cape Playhouse in Dennis, and straight off he is playing a lead, in Kenyon Nicholson’s

The Barker,

a Broadway hit of the previous year. Then he moves down to the armpit of the Cape—to Falmouth, where he tries out for a troupe called the University Players Guild.

He enters laughing. Joshua Logan, a Princeton undergraduate, is onstage in a comedy. He begins to speak, and “a high, strangulated sob came from the darkness,” Logan will later write. “I thought someone was having an asthma attack.” Logan imagines the sound issuing from “some odd human animal.”

Begun by two Harvard students, Bretaigne Windust and Charles Leatherbee, the UPG is, like the Omaha Community Playhouse, powered by Progressive sentiment and populist ideals, presenting a repertory of recent Broadway hits, murder mysteries, and melodrama. There is also an aspect of pioneering to the venture: The group is in the process of constructing its theater on the outskirts of West Falmouth, and Henry is put to work painting walls, hammering nails, and wiring spotlights. Soon he will be making theater on a stage he has helped build.

A gangly gawker hailing from regions most of the Princeton boys and Vassar girls have never seen, Fonda draws their fascination at once. Logan, eventually to become Henry’s close friend and collaborator, notes his oddly “concave chest” and “protruding abdomen,” his “extraordinarily handsome, almost beautiful face and huge innocent eyes.”

Fonda’s parts at the UPG are a mix of whatever comes his way. He is first seen in

The Jest,

an Italian Renaissance costume piece; Fonda plays, of all things, an elderly count. Despite his intelligence and lack of upper-body muscle, Fonda is next cast as a brainless boxer in a sporting comedy,

Is Zat So?

At this, he does better: Young Henry is gifted at embodying subverbal man-beasts. In improvisation with Logan, he even transforms himself into ten-year-old Elmer, a small boy who mimics fish and birds.

Henry is also in touch with his darker aspects. Though popular and convivial, he shows an innate seriousness and a tendency to stormy moods. In Sutton Vane’s

Outward Bound,

he incarnates a dead man adrift in the afterlife. “Several years ago in a New York theatre,” writes the Falmouth reviewer, “when Alfred Lunt found himself aboard a ghost ship outward bound for heaven or hell, he cast over his audience an eerie spell which we thought could never be repeated. But Henry Fonda repeated that experience for us in his excellent interpretation of the same role in the same play.”

A key lesson in Fonda’s creative education comes when he reprises his hometown success,

Merton of the Movies

. “[N]ow he was aware,” stage manager and set designer Norris Houghton writes, “of the presence of the audience and its response to him, of which he had had no consciousness in Omaha.” As Fonda is less Merton, he is more himself embodying Merton in a self-aware process—mastering the actor’s ability to distance himself from the action so as to achieve control over character and affect, while each time believing in the act sufficiently to appear spontaneous. Fonda was “learning the technique of acting without realizing it … learning for himself such elements of what is known in the ‘Stanislavsky System of acting’ as ‘emotion memory.’”