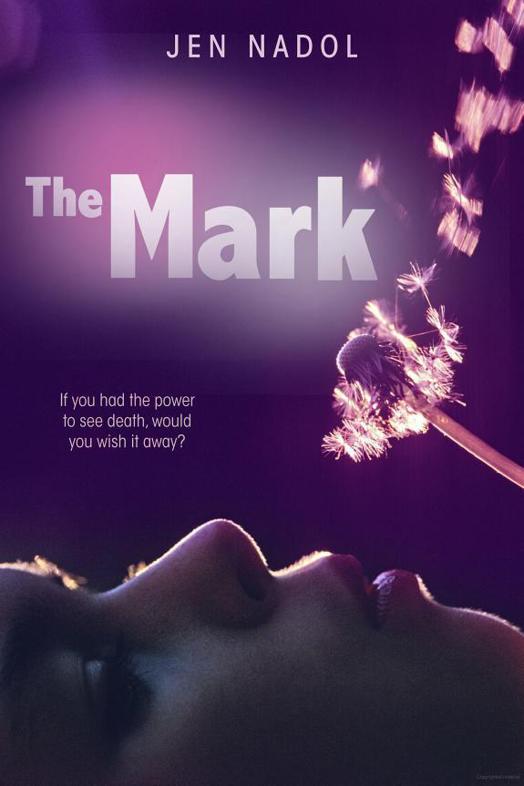

The Mark

Authors: Jen Nadol

The Mark

JEN NADOL

NEW YORK BERLIN LONDON

for my family

Table of Contents

There is nothing like the gut-hollowing experience of watching someone die, especially when you know it’s coming.

I saw the man with the mark at the bus stop on Wilson Boulevard when I crossed Butter Lane on my way to school, the route I took every day. I wanted to look away, pretend he wasn’t there, and run for the safety of algebra and honors English, but I didn’t. I had promised myself. So I turned right and walked two blocks to the Plexiglas shelter, where we stood silently. It was a misty March day, the chill of winter still in the air. I slid my hand into the outer pocket of my book bag and felt for the change that always jangled around in there. I was counting out eighty-five cents for the ride when he asked, “You know when the B3 comes?”

His skin was smooth and his dark hair threaded with the slightest of gray. He was younger than I’d expected, than I’d have hoped. It limited the possibilities in an unpleasant way. I looked down, trying to ignore the hazy light that surrounded him.

“I think the schedule’s on the wall.”

“Yeah, I saw it. The bus should have been here five minutes ago.” We both turned away, watching the street.

“So you don’t know if it’s usually late?” he asked without looking back at me.

“No.”

He checked his watch, then pulled out a cell phone, exhaled sharply, and put it away. Reception was always lousy here. I pretended to be busy smoothing the folds of my skirt while I watched him from beneath overgrown bangs, glimpses of his ironed trench coat and gleaming shoes filtered as if seen through a bar code. He never glanced my way, but why would he? With my slight frame, I was forever being mistaken as young, but the thrift-store kilt and ponytail I’d worn today probably made me look more like six than sixteen. Hardly worth his notice.

The bus crested the hill finally,

B3 Oak Park

glowing yellow through the light fog. I liked to ride the buses around our little town, just to explore. I walked through neatly groomed neighborhoods or wandered the five square blocks of Ashville center. Some of the shopkeepers knew me: Mr. Williams, the grocer on Spring Street, and Juan at the newsstand. Mostly they ignored me, the way people do who have little interest in anything but getting through the day. But I knew them. I’d watched Mrs. Leshko put out her deli leftovers for the town cats, and Burt Keyes from the convenience store steal extra papers from the Main Street machine.

From my travels, I knew this bus would go through our suburbs into downtown, then to the small communities on the west side. Not that the route mattered. I’d have followed him anywhere.

I sat three rows behind, too nervous to do anything but pick my nails and keep watch. We passed residential streets, under maple trees heavy from the night’s rain, adding passengers as we went. When we approached downtown, the man collected his briefcase and umbrella, standing for the Court Street stop. Reluctantly I hefted my bag and followed him off the bus, still nurturing a small hope somewhere that I was wrong.

He walked quickly. I had to trot to keep up, my book bag thumping awkwardly against my back. Without breaking stride he pulled the cell phone from his pocket. I missed his first words in the rush of traffic, but those after were impossible not to hear.

“For crissake, Lorraine! How could the goddamn computer be down?” He paused, stopping short to peer into his briefcase. He’d caught me by surprise and I stopped too, a woman jarring me from behind.

“Sorry,” I muttered. She passed, scowling. I shuffled over to the nearest building and leaned against the wall. My backpack, laden with schoolwork I’d slogged through last night for assignments that would now be late, slid to the ground.

“Here it is,” he said, yanking a small black book from his bag. He was a rock in the stream of pedestrian traffic, people turning their bodies to slide by with minimum disruption to their morning rush. “Well, that’s just great,” he said, staring at the opened calendar. “I was due in Judge Shenkman’s chambers twenty minutes ago. Why didn’t you call … Forget it …” He tilted his head skyward, searching for rescue from her stupidity. “Just call him now. Explain that my car was broken into. Also, call my wife and remind her to get ahold of the insurance people. And get tech support to fix the damn computer. That’s what I pay you for—to manage the details.” He snapped the phone shut and thrust it into his pocket.

“Not my fucking day,” I heard him mutter as he started walking again.

He had no idea.

At Linden Street, he turned the corner, hurrying toward the rear of the courthouse and the law buildings that surrounded it. I stayed with him, but started to wonder what I’d do when he got to his office or the courthouse. I hadn’t really planned this out, but obviously I couldn’t follow him in. I’d wait outside, I thought, wishing I had something other than textbooks with me. This could be a long day. I knew I was chicken, but deep down I hoped maybe it would happen inside, somewhere I wasn’t allowed.

I needn’t have worried. We were at the end of the block, me still trailing a few paces behind. As the man stepped off the curb, I saw the elements coming together—the wet street, his head bent checking the time again, then snapping up at the screech of brakes, a crunch like nothing I’ve ever heard: of bone and metal and shards of plastic, screams, the people hurrying to work frozen, then running to the street or away from it.

I stood still, book bag at my feet, and forced back dry heaves, thankful I’d skipped breakfast. An ambulance’s wail rose over the commotion, the ebb and flow of its siren mournful as it sped the three blocks from Ashville General. EMTs would be on the scene within minutes.

I could have told them not to bother.

I didn’t remember getting back on the bus, but rose from my seat by rote as we approached my stop. I stood for a moment, alone in the bus shelter, the rain coming down hard now, and looked at the spot where the man had waited less than an hour ago.

I thought about his people: Lorraine nervously dialing the judge to tell him about her boss’s delay, now permanent. His wife, somewhere nearby, maybe on the line with their insurance agent or making coffee or bundling kids off to school, not realizing that all of those things would soon come to a sharp and screeching halt, never to be done with the same emotion again. Then there were his coworkers and the man who sold him coffee or a newspaper or cut his hair—the ripples of his death, any death, stretching on and on.

As I walked home I kept replaying it. Blood and broken glass on the pavement. The wide, unseeing eyes of the man who had hit him and the cell phone spinning brokenly on the shiny asphalt. I didn’t know what was worse: what I had seen or what it meant.

Nan was in the living room when I let myself into our apartment. I heard a yoga video and her steady breathing that paused when the door slammed shut behind me.

“Cass, is that you?”

“Yeah.” I tossed my bag to the corner near my room, its heavy thud reminding me briefly of school. The thought of going back there after today was both comforting and incomprehensible. The foyer was filled with the sweet, rich smells of cinnamon, allspice, and cloves. Nan was brewing homemade tea—my grandmother, using her own grandmother’s Corinthian recipe.

“What are you … Oh, sweetie, you’re soaked!” I watched Nan’s feet as she hurried from the living room across the foyer to where I stood. They were bare, her deep maroon pedicure stark against translucent skin. She cupped my chin and drops of rain—or maybe it was tears—fell onto her wrist.

“What happened?”

I took a breath, cleansing, as her video would say, but my voice still shook. “I saw one today.”

She inhaled sharply and seemed almost as afraid to ask as I was to tell; but Nan would never shy away from something that needed doing, no matter how unpleasant. “And?”

I nodded and Nan put her arm around me. “Oh, Cassie. Oh, baby, I’m so sorry.” Gently she led me through open French doors into the living room and lowered me to the sofa. The thought crossed my mind that I’d leave a big wet spot on the slipcover, but it didn’t bother Nan. She squatted, holding both of my hands in hers, and searched my teary face.

Nan’s black eyes were sharp and framed with long lashes, paler now than the charcoal of the faded photo on her dresser. She had once been beautiful—it always surprised me how I could still see it in her face—but it was her spirit, an old friend of hers once told me, more than her exotic Mediterranean looks that had charmed the boys of their childhood neighborhood. Like me, she was short and small-boned but far from frail. There was an unmistakable strength to Nan, both inner and outer. Though her dark hair was now white and her olive skin no longer smooth over prominent cheekbones, Nan was anything but a little old lady.

“Stay here,” she said. “I’m going to get you some towels.” She crossed the room, deftly turning the TV off and the stereo on, before passing back through the French doors. Mozart played softly. I leaned back, the sofa getting wetter, and let the rising notes from strings, slightly melancholy, wash over me as I tried not to think.

Nan was back a minute later with two fresh Turkish towels, warm from the radiator they’d been draped over, and a change of clothes.

“Here. Dry off; get comfortable while I make you something hot to drink.”