The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle That Changed the World (34 page)

Read The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle That Changed the World Online

Authors: Holger H. Herwig

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War I, #Marne, #France, #1st Battle of the, #1914

The attacks on Bayon and the charge through the Trouée de Charmes were canceled. The great host of 272 guns was to be assembled before the Grand Couronné. The attack was set for the night of 4–5 September. Gebsattel’s Bavarian III Corps, which had largely been spared the fighting around Nancy and thus denied battle honors,

53

would spearhead the assault.

“NEVER DO WHAT THE

enemy wants for the very reason that he wants it,” the great Napoleon had counseled a century before. “Avoid a battleground that he has reconnoitered and studied, and with even more reason ground that he has fortified and where he is entrenched.”

54

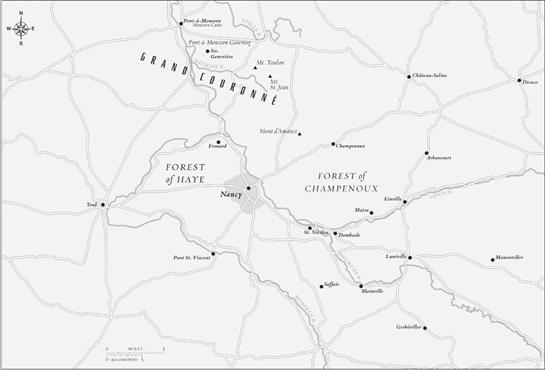

As is often the case, sound advice grounded in solid history was ignored. The Grand Couronné northeast of Nancy constitutes a plateau scarp that in the north is a mere ridge broken by buttes and mesas, but that near Nancy becomes wider and forms “an eastward projecting bastion measuring half a dozen miles from the [Moselle] to its apex.” The entire plateau of the Grand Couronné is “breached by transverse stream valleys”

55

and erosion gaps. Attacking infantry from the north and northeast would have to batter their way across the plateau to assault Nancy. Key to the French defenders was the so-called Pont-à-Mousson Gateway, a broad opening in the Grand Couronné that cut the plateau east to the Moselle. It was protected by two pillars: the Mousson butte, to the north, and the Sainte-Geneviève Plateau, to the south.

As well, the French had carefully prepared the defenses around Nancy—and especially on the ridges of the Grand Couronné. It was one of the many ironies of the war that this work had been ordered by Foch, the apostle of the all-out offensive, after he assumed command of XX Corps at Nancy in August 1913. The French had left Nancy unfortified because it projected dangerously in front of the line of forts they had constructed in the 1880s through Toul, Épinal, and Belfort. Foch obviously thought Nancy worth saving from attack.

Specifically, Foch’s engineers had extended the defensive works three kilometers out to the heights of Malzéville. They had studded every approach to the escarpment with forts, artillery, machine guns, and barbed wire. They had dug deep trenches across roads and rail beds to slow the enemy advance. They had calibrated every piece of ground for the heavy Rimailho artillery as well as the

soixante-quinzes

. They had concealed much of this firepower in the ravines that dissected the Grand Couronné. Even geography had played into their hands. To the north of Nancy, 150-to 200-meter-high ridges shot straight up from the western banks of both the Meurthe and Moselle rivers, offering defenders a natural bulwark. The fallback position west of Nancy across the Moselle trench was even more formidable: The high plateau of the Forest of Haye in the angle formed by the Meurthe and the Moselle bristled with artillery emplacements and concrete forts. In between lay three water obstacles: the Mortagne River, 8 to 15 meters wide and 1.2 meters deep; the Moselle, 70 to 100 meters wide and between 0.60 and 1.50 meters deep; and the Canal de l’Est, 18 to 22 meters wide and 2.2 meters deep. All three would have to be crossed by the Bavarians after they had seized Nancy.

56

French units, refreshed after the Battle of the Trouée de Charmes, were assigned positions around Nancy for the expected German assault.

57

Castelnau deployed four corps of Second Army on the heights north and northeast of the city, with Jean Kopp’s 59th Reserve Infantry Division (RID) at Sainte-Geneviève and Émile Fayolle’s 70th RID at Amance. He then sited half of Pierre Dubois’s IX Corps southeast of Nancy behind the Meurthe: Émile Brun d’Aubignosc’s 68th RID at Saffais, Louis Espinasse’s XV Corps at Haussonville behind the Mortagne, and Louis Taverna’s XVI Corps as well as Louis Bigot’s 74th RID near Belchamp. Dubail placed Joseph de Castelli’s VIII Corps east of the Forest of Charmes and César Alix’s XIII Corps around Rambervillers. Léon Durand’s Second Reserves Group (three divisions) was divided among the active units. Émile-Edmond Legrand-Girarde’s XXI Corps was the last to arrive.

58

But this formidable concentration was short-lived. Joffre was so confident of Nancy’s defenses that between 31 August and 2 September, he continued to strip his forces there to bolster the front around Paris. Unit by unit, Second Army had to surrender Espinasse’s XV Corps, three brigades of Dubois’s IX Corps, Justinien Lefèvre’s 18th ID, Camille Grellet de la Deyte’s 10th CD, and a chasseur brigade. First Army entrained Legrand-Girarde’s XXI Corps, bound for Paris.

59

It now consisted mainly of Castelli’s VIII Corps and Pierre Roques’s XII Corps, 167,300 effectives and 5,400 sabers in all.

60

Joffre was no longer interested in tying down

(fixer)

German forces in Lorraine, but merely in making a stand

(durer)

east of Nancy.

61

By 4 August, Castelnau’s Second Army consisted of Taverna’s XVI Corps and Maurice Balfourier’s XX Corps (nine infantry divisions), Foch’s former unit, as well as the reserves (ten infantry divisions), roughly 120,500 soldiers as well as 3,800 cavalrymen and 536 pieces of artillery.

62

Still, Second Army alone was superior to the attacking Bavarian Sixth Army.

NANCY AND THE GRAND COURONNÉ

THE ASSAULT ON THE

Grand Couronné began a day ahead of schedule, in the heavy, humid night of 3–4 September. The air pressure caused by the massive artillery barrage was so powerful that it blew out the doors at Bavarian I, II, I Reserve, XIV, and XXI corps headquarters.

63

In the morning, Crown Prince Rupprecht pushed his right wing north of Nancy along the Saffais Plateau and sent his left against Épinal. As well, he ordered Seventh Army to advance on Rambervillers, northeast of Épinal. Comprising mostly Landwehr formations, it quickly became bogged down in vicious hand-to-hand combat. Heavy fighting also ensued along the Meurthe River. But the main assault consisted of a frontal infantry attack on the Grand and Petit Mont d’Amance, northeast of Nancy, as well as Forts Saint-Nicolas-de-Port and Pont-Saint-Vincent, southeast of Nancy, and Frouard, northwest of Nancy. It was now or never on the

Südflügel

.

The desperate nature of the fighting immediately became apparent. At Mandray, a village ten kilometers southeast of Saint-Dié, the battle raged from house to house.

64

French artillery on the Grand Couronné poured fire on the tight German waves as they attempted to cross the plains below. Chasseurs ferociously defended Mandray at every corner, finally retiring on the church. The soldiers of Eugen von Benzino’s Ersatz division blew open its barricaded door. With trumpets sounding the charge, the Bavarians stormed the sanctuary. They set the wooden stairs leading to the steeple on fire. The chasseurs there never had a chance.

At Maixe, a hamlet of five hundred people on the Marne-Rhine Canal, German reserves took a terrible pounding for fifteen hours from well-hidden French artillery, accurately directed by fliers.

65

The Bavarian history of the war recorded, “Soon Hell broke loose. French heavy and light artillery shells whistled over our heads with their ear-shattering screams and their shrapnel, and the entire region was soon enveloped in a thick haze of smoke and dust.” Even well-dug-in infantry companies were hit hard. “Human torsos and individual [body] parts flew through the air” from wagons that had been abandoned in the village square. “Everywhere there was horror and despair, death and perdition; everywhere, there were wild screams of pain and fear.” Horses, as if whipped, ran about in panic, taking with them wagons and artillery caissons. The wounded screamed horribly—and had to be abandoned.

On 4 September, Sixth Army concentrated its artillery fire on the front along the Meurthe between the Forest of Vitrimont and Courbesseaux, but could not drive the French out. The next day, Rupprecht’s gunners shifted their fire to the area northeast of Nancy; roughly three thousand shells rained down on the Amance heights. Xylander’s I Corps fired off a thousand howitzer rounds on 5 September. Day and night the deafening artillery duel continued. Wave after wave of gray-clad Bavarian infantry debouched from the Champenoux Forest under cover of darkness to storm the front of the Grand Couronné—only to be cut down by murderous cross fire from the French 75s concealed on reverse slopes of the Mont d’Amance mesa and the Pain de Sucre butte guarding the eastern and southern approaches to the Grand Couronné. Still, the future of

la position de Nancy

hung by a thread on the second day of Rupprecht’s offensive.

Castelnau’s earlier optimism evaporated. He feared a repetition of the Battle of the Saar—decimation of Second Army if it stubbornly clung to defending the Grand Couronné. Reports from Durand’s reserve divisions and Balfourier’s XX Corps revealed that Second Army, recently depleted by Joffre, could not long withstand the Bavarian assault. At 2:30 PM on 5 September, Castelnau telegraphed the Grand quartier général (GQG): “I cannot depend upon a prolonged resistance.” He suggested a “timely withdrawal” behind the Meurthe and Moselle rivers, to the Forest of Haye or to the heights of Saffais and Belchamp—and perhaps even beyond.

66

Joffre was not amused. Unlike his German counterpart, he never lost sight of the overall campaign and never gave in to momentary situations, no matter how dire they appeared. Thus, he began his

“très urgent”

epistle to Castelnau at 1:10

PM

on 6 September with a lecture on strategy. “The principal mass of our forces is engaged in a general battle [along the Marne] in which the Second Army, too remote from the scene of operations, cannot take part.” If Second Army suddenly retreated to the line Belfort-Épinal, the two French armies in Lorraine would be separated from each other and defeated piecemeal. If First Army joined Castelnau’s retreat, all of Franche Comté, along with its capital, Besançon, and the major fortress Belfort, would be lost and the right wing threatened with envelopment and annihilation. Joffre deemed it “preferable” that Castelnau maintained his “present position” at Nancy “pending the outcome of this battle.”

67

The “little monk in boots” well understood the understated meaning of the term

préférable

. Incredibly, after the war he would claim that he had heroically resisted Joffre’s “order” to abandon Nancy. It became another legend of the Battle of the Marne.

Castelnau dug in. The French right in the area of Rehainviller-Gerbéviller held firm, staunchly defended by Taverna’s XVI Corps and Espinasse’s XV Corps, shattered earlier at Sarrebourg, as well as by Bigot’s 74th RID and Charles Holender’s 64th RID. The center and the left of the line from the Sânon River to the Forest of Champenoux saw the fiercest fighting, with outposts and villages frequently passing from one hand into the other.

The battle for Nancy reached its climax on 7 September. The Bavarians advanced out of the north from the Pont-à-Mousson Gateway and three times furiously stormed the north front of the Grand Couronné with flags unfurled and bands playing. The village of Sainte-Geneviève and the Mont Toulon ridge commanding the southern side of the gateway witnessed brutal bayonet charges throughout the night. If they could be taken, the way would be opened for the Bavarians to march up the Moselle to Nancy, storm the vital Mont d’Amance defensive works from the rear, and shatter the entire French defensive network on the Moselle Plateau.

68

The German assault almost worked. Several units from 314th IR of General Kopp’s French 59th RID accidentally abandoned Sainte-Geneviève, nicknamed the “Hole of Death” by its defenders.

69

But by 8 September, the French had retaken the village, thanks in large measure to the gallant counterattacks of Balfourier’s XX Corps and the fact that the Bavarians had not detected the French withdrawal. More than eighty-two hundred German dead littered the battlefield; Baden XIV Corps suffered ten thousand casualties. The forests around Nancy had seen desperate bayonet charges. At one place, in the dark of night two Bavarian soldiers of Gebsattel’s III Corps had bayoneted each other; next morning a patrol found their bodies thus “nailed” to two trees.

70

General von Gebsattel had finally experienced the battle he’d yearned for so desperately. It was not at all the glorious venture that he had imagined. His corps had advanced into an “undoubtedly cleverly prepared battlefield” studded with “far-ranging French guns.” Bavarian artillery had been unable to gain any “significant advantage” because its spotters could not detect the sources of hostile fire. Each night, the enemy had moved its units from one “well prepared position into another.” His own infantry had been unable to close with the French. “Everywhere trenches and advance guards and rear-echelon reinforcements.”

71

It was siege-style warfare at its worst.