The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle That Changed the World (49 page)

Read The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle That Changed the World Online

Authors: Holger H. Herwig

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War I, #Marne, #France, #1st Battle of the, #1914

The Valley of the Aisne constitutes a deep depression with the river running east to west and in many places too deep to ford. Its slopes consist of rough woods and thickets. A ridge, 150 meters above the river and traversed by a forty-kilometer road, the Chemin des Dames, built by Louis XV for his daughters, provided German artillery with superb observation posts. For four soggy and bloody days, Franchet d’Espèrey’s Fifth Army, Maunoury’s Sixth Army, and Sir John French’s BEF assaulted the German defensive line, moving over battle-scarred terrain littered with abandoned wounded, munitions, supplies, stragglers, and thousands of drained wine bottles—to no avail. By 18 September, a “surprised” Joffre scaled back the Battle of the Aisne as it became clear that frontal assaults on well-dug-in German artillery, machine-gun, and infantry positions (“very serious fortifications”) had dashed all “hope for a decision in open terrain.”

131

In the center of the French line, neither Third Army nor Fourth Army made any appreciable progress. Once more, Joffre took out his frustration on Sarrail. “I do not understand how the enemy was able to get away 48 hours ago without your being informed of it,” he acidly lectured the general by telephone. “Kindly institute an inquiry immediately on this matter and let me know the results at once.”

132

Sarrail evaded a formal inquiry by having his staff telephone GQG with a routine progress report.

133

Foch, freshly invigorated, drove Ninth Army in pursuit north-northeast with the aim of “destroying” the German army.

134

Pounding rain rendered the chalky roads of the Champagne virtually impassable. At Fère-Champenoise, Foch’s soldiers found ransacked wine cellars and the streets strewn with empty wine bottles. At 8

PM

on 11 September, Justinien Lefèvre’s 18th ID entered Châlons-sur-Marne; at 7:45

AM

the next day it began to cross the Marne.

135

The Germans’ retreat had been so hasty that they had not had time to activate the demolition charges attached to the bridges. That night Foch dined at the Hôtel Haute-Mère-Dieu, where the night before the chefs had prepared a “sumptuous meal” for Saxon crown prince Friedrich August Georg and his staff.

136

In truth, men, horses, and supplies had been exhausted. On 20 September, Franchet d’Espèrey dejectedly instructed his corps commanders simply to “stand and hold.”

137

The next day Joffre in a “lapidary manner” instructed Foch by telephone, “Postpone the attack. Inform [commanders] to economize ammunition.”

138

What the French official history of the war calls a “threatening ammunition crisis” had developed for the artillery.

Les 75s

had started the war with 1,244 shells per gun, but those stocks had been fired off and the daily production of at best 20,000 shells did not begin to meet the requirements for the three thousand

soixante-quinzes

in service.

139

An obvious “shell crisis” was at hand well before the end of September 1914. To the great relief of British and French commanders, the Germans were equally fatigued. The III Corps of Kluck’s First Army, to give but one example, between 17 August and 12 September had marched 653 kilometers with full combat packs, had fought the enemy for nine full days, and had had zero days of rest.

140

In a final bid for victory, Joffre used his superb railroad system to shift forces (IV, VIII, XIV, and XX corps) from his right to his left. In a feat of logistical brilliance, the Directorate of Railways moved the corps in about four to six days on roughly 105 to 118 trains each.

141

Yet again, the sought-after final victory eluded Joffre. He blamed it on “the slowness and the lack of skilled maneuvering displayed by the two flank armies and Fifth Army.”

142

His staff calculated that the French army in September had suffered 18,073 men killed, 111,963 wounded, and 83,409 missing.

143

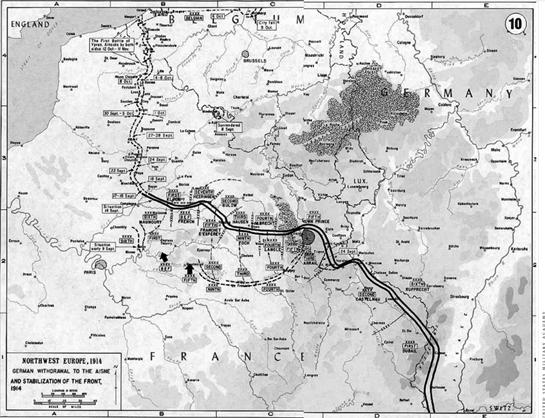

Several belated attempts by each side between 17 September and 17 October to turn the flank of the other—the so-called race to the sea—ended in deadly deadlock.

*

The great war of maneuver turned into siege-style warfare in the blood-soaked fields and trenches of Artois, Picardy, and Flanders.

*

Moltke had been forced out of office the day before, and the rest of the senior staff was occupied with the withdrawal to the Aisne; none initialed Hentsch’s report.

†

Interestingly, Dommes was the “patriotic censor” who in May 1919 on behalf of the army and the Foreign Office convinced Moltke’s widow, Eliza, not to publish the general’s memoirs, titled

Responsibility for the War

, as their contents could bring about a “national catastrophe” at a time when the Allies were hammering out peace terms in Paris. Dommes (and Tappen) denied that Hentsch in September had been given “full power of authority” by Moltke. Both Dommes and Tappen after the war denied that Hentsch and Moltke had met privately shortly before Hentsch departed on his tour of the front. And both Dommes and Tappen were highly active in selecting materials for the Reichsarchiv to use in writing the volume dealing with the Battle of the Marne.

*

Greenwich Mean Time. German accounts give German General Time (one hour later).

*

A junior staff officer had accidentally ordered this configuration of the baggage wagons.

*

Exophthalmic goiter, also known as Graves’, Parry’s, or Basedow’s disease.

*

Grand Duke Nikolai Ivanov’s Russian army took 130,000 prisoners and inflicted 300,000 casualties on Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf’s forces between 26 August and 11 September 1914.

*

In 1813–15, Field Marshal Gebhard von Blücher had fought with the Duke of Wellington against Napoleon I.

*

The French official history gives the dates 20 September–15 October for

la course à la mer

. AFGG, 4:127.

EPILOGUE

Everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult

.

—CARL VON CLAUSEWITZ

T

HE BATTLE OF THE MARNE WAS A CLOSE-RUN THING. IT CONFIRMED

yet again the Elder Helmuth von Moltke’s famous counsel that no plan of operations “survives with certainty beyond the first encounter with the enemy’s major forces.”

1

And it reified yet again Carl von Clausewitz’s dictum that “war is the realm of uncertainty; three quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty.”

2

Nothing about the Marne was preordained. Choice, chance, and contingency lurked at every corner.

Senior commanders on both sides did not at first understand the magnitude of the decision at the Marne. It seemed simply a temporary blip on the way to victory. The armies would be rested, reinforced, re-supplied, and soon again be on their way either to Berlin or to Paris. Below headquarters and army as well as corps commands, a million men on either side likewise had no inkling of what “the Marne” meant—except more endless marches, more baffling confusion, and more bloody slaughter. Future historian Marc Bloch, a sergeant with French 272d Infantry Regiment, on 9 September recalled marching down a “tortuously winding road” near Larzicourt on the Marne at night, oblivious to the fact that the great German assault had been blunted. “With anger in my heart, feeling the weight of the rifle I had never fired, and hearing the faltering footsteps of our half-sleeping men echo on the ground,” he drearily noted, “I could only consider myself one more among the inglorious vanquished who had never shed their blood in combat.”

3

THE FRONT STABILIZES AT THE AISNE RIVER

The Battle of the Marne did not end the war. But if it was “tactically indecisive,” in the words of historian Hew Strachan, “strategically and operationally” it was a “truly decisive battle in the Napoleonic sense.”

4

Germany had failed to achieve the victory promised in the Schlieffen-Moltke deployment plan; it now faced a two-front war of incalculable duration against overwhelming odds. A new school of German military historians

5

goes so far as to suggest that Germany had lost the Great War by September 1914.

Still, “what if?” scenarios abound. What if Germany had not violated Belgium’s neutrality; would Britain still have entered the war? What if Helmuth von Moltke had not sought a double envelopment of the enemy in Alsace-Lorraine

and

in northern France; could at least half of the 331,000 soldiers on the left wing have helped the right wing to victory? What if he had not sent III and IX army corps to the east; could one of those have filled the famous gap between Second and First armies on the Marne, and the other helped Third Army break French Ninth Army’s fragile front at the Saint-Gond Marshes? What if the commanders of German First and Second armies had simply refused to follow Lieutenant Colonel Richard Hentsch’s “recommendation” to retreat from the Marne; could German First and Second armies have held on the Ourcq and Marne rivers, with possibly war-ending results?

What if Joseph Joffre had not been the French commander in chief? What if he had been cashiered in late August after he had been soundly defeated in the Battle of the Frontiers and after his deployment Plan XVII had totally collapsed? What historian Sewell Tyng called Joffre’s “inscrutable, inarticulate calm,” his “placid, unsophisticated character,” and his “far-sighted, unsentimental, determined” leadership were among the major reasons why the French did not repeat their collapse of 1870–71.

6

After the war, Marshal Ferdinand Foch paid due tribute. Immediately after the loss of the Battle of the Frontiers, Joffre had recognized that “the game had been poorly played.” He had broken off the campaign with every intention of resuming it as soon as he had “repaired the weaknesses discovered.” Once clear on “the enemy’s ultimate intentions” by marching across Belgium, Joffre had shifted forces from his right wing to his left, had cashiered general officers whom he found to be “not up to standard,” had orchestrated an orderly withdrawal behind the Marne and Seine rivers, had created Michel-Joseph Maunoury’s new “army of maneuver” in the west, and had launched his great attack between “the horns of Paris and Verdun” when he deemed the moment favorable. “When this moment arrived, he judiciously combined the offensive with the defensive after ordering an energetic about-face,” Foch opined. “By a magnificently planned stroke he dealt the invasion a mortal blow.”

7

The contrast with the lethargic, doubting, distant, “physically and mentally broken” Younger Moltke need not be belabored.

What if French morale had cracked after the Battle of the Frontiers? Campaigns are not fought against lifeless bodies. The enemy reacts, innovates, surprises, and strikes back. Were it not for the “emotions” and the “passions” of the troops, Carl von Clausewitz reminds us, wars would not escalate and might not even have to be fought. “Comparative figures” of opposing strengths would suffice to decide the issue without having to resort to “the physical impact of the fighting forces.” Put differently, “a kind of war by algebra.”

8

But in 1914, the French

poilu

surprised the Germans with what Moltke called his

élan

. “Just when it is on the point of being extinguished,” he wrote his wife at the height of the Battle of the Marne, it “flames up mightily.”

9

Karl von Wenninger, the Bavarian military plenipotentiary at Imperial Headquarters, likewise expressed his surprise at the enemy’s tenacity. “Who would have expected of the French,” he wrote his father on 9 September, “that after 10 days of luckless battles a[nd] bolting in open flight they would attack for 3 days so desperately.”

10

General Alexander von Kluck gave the adversary his full respect in 1918. “The reason that transcends all others” in explaining the German failure at the Marne, he informed a journalist, was “the extraordinary and peculiar aptitude of the French soldier to recover quickly.” Most soldiers “will let themselves be killed where they stand;” that, after all, was a “given” in all battle plans.

But that men who have retreated for ten days … that men who slept on the ground half dead with fatigue, should have the strength to take up their rifles and attack when the bugle sounds, that is a thing upon which we never counted; that is a possibility that we never spoke about in our war academies.

11

Perhaps the greatest “what if?” scenario: What if Kluck’s First Army had indeed turned the left flank of Maunoury’s Sixth Army northeast of Paris? For most German military writers and the German official history of the war,

Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918

, this was a “certainty.” Victory assured. End game. War over. But Moltke’s chief of operations, Gerhard Tappen, stated after the war that he was not so sure. He, the Gabriel ever trumpeting victory throughout August and early September 1914, conceded that even Kluck’s triumph at the Ourcq River would not have been “decisive” to the overall war effort. Given the dogged “tenacity” of the British and their “well known war aims,” the war would have dragged on.

12

Even if thereafter First Army had pivoted on its left and squared off with the three army corps of the BEF and Louis Conneau’s cavalry corps, the end result likely would have been utter exhaustion for the armies on both sides. Stalemate. An honest appraisal from one not known for candor. And yet, did Kluck not owe it to both his troops and the nation to have fought the battle through to conclusion?

The campaign in the west in 1914 revealed two distinct command styles. Moltke was content to remain at Army Supreme Command headquarters far removed from the front—first in Koblenz and then in Luxembourg—and to give his field commanders great latitude in interpreting his General Directives. He chose not to exercise close control over them by way of telephones, automobiles, aircraft, or General Staff officers. After all, they had conducted the great annual prewar maneuvers and war games and as such could be counted on to execute his “thoughts.” Already, in peacetime, Moltke had let it be known that it sufficed for “Commanding Generals” simply to be “informed about the intentions of the High Command,” and that this could easily be accomplished “orally through the sending of an officer from the Headquarters.”

13

The reality of war proved otherwise. Some commanders failed the ultimate test, war, mainly because of a lack of competence (Max von Hausen); some partly because of advanced age (Karl von Bülow); and others partly because of ill health (Helmuth von Moltke, Otto von Lauenstein).

General Moriz von Lyncker, chief of the Military Cabinet, struck at the heart of the matter on 13 September. “It is clear that during the advance into France the necessary tight leadership on the part of the Chief of the General Staff had been totally lacking.”

14

The next day he convinced Wilhelm II to place Moltke on “sick leave.” But while more than thirty German generals were relieved of command of troops in 1914, there was no general “housecleaning” at the very top. Three army commanders were beyond reach, of course, because they were in line for future crowns: Wilhelm of Prussia led Fifth Army until August 1916, when he took command of Army Group Deutscher Kronprinz for the rest of the war; Rupprecht of Bavaria headed Sixth Army until August 1916, when he was given charge of Army Group Kronprinz Rupprecht until November 1918; and Albrecht of Württemberg stayed with Fourth Army until February 1917, when he assumed command of Army Group Herzog Albrecht for the duration.

Not even the two most controversial army commanders were sacked after the Battle of the Marne. Karl von Bülow, who had shown less than boldness first at the Sambre and then at the Marne, not only was promoted to the rank of field marshal in January 1915 and awarded the order Pour le Mérite, but was rewarded for his mediocre performance by (again) being given command of First Army and then of Seventh Army as well. He led Second Army until April 1915, when he was temporarily relieved of command due to a stroke. He was forced to retire two months later; his pleas to be reinstated fell on deaf ears. Alexander von Kluck, who had disobeyed Moltke’s orders and turned in southeast of Paris, commanded First Army until March 1915, when near Vailly-sur-Aisne he was severely injured in the leg by shrapnel. He turned seventy while recuperating and in October 1916 was retired. Max von Hausen was the only army commander relieved of duty, and that came about mainly due to a severe case of typhus. His desperate appeals to be reinstated also went unanswered.

After the Battle of the Marne, the German army of 1914 was gone forever. Its tidy division into federalist Baden, Bavarian, Prussian, Saxon, and Württemberg contingents ended, never to be revived. In the words of former Prussian war minister Karl von Einem, the new commander of Third Army, “The army totally loses its wartime separateness. Everything is moved about, divisions and brigades are thrown together. It is living from hand to mouth.”

15

In short, a true “German” army fought the Great War for the next four years.

Joseph Joffre, on the other hand, played a highly active, indeed intense, role in French decision making. Apart from issuing a host of General Instructions, Special Instructions, and Special Orders, he showered his army commanders with hundreds of “personal and secret” memoranda, telephone calls, and individual orders. He used his driver and automobile to great advantage, constantly on the road to inspect, to order, to encourage, and, where necessary, to relieve. In fact, Joffre filled a park with so-called

limogés.

*

These included, by his reckoning, two army, ten corps, and thirty-eight division commanders.

16

Some (Charles Lanrezac) he fired because he considered them to be overly pessimistic or willing to challenge his orders; others (Pierre Ruffey) because he found them to be unnecessarily “nervous” and “imprudent” in their dealings with subordinates. He maintained in command a core of loyal and aggressive army commanders (Fernand de Langle de Cary, Yvon Dubail, Édouard de Castelnau), and he promoted several corps commanders (Louis Franchet d’Espèrey, Ferdinand Foch, Maurice Sarrail) who had “faith in their success” and who by “mastery of themselves” knew how to “impose their will on their subordinates and dominate events.”

17

He never regretted his sometimes unjustified firings. He declined after the war to engage the “victims” in a war of memoirs.