The Marriage Book (63 page)

Authors: Lisa Grunwald,Stephen Adler

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Marriage & Long Term Relationships, #General, #Literary Collections

After her husband’s death her health improved, and in a year or two she entered into a new relation with a man who was aware of women’s needs and spent sufficient time and attention to them to ensure a successful completion for her as well as for himself. The result was that she soon became a good sleeper, with the attendant benefits of restored nerves and health.

Sleep is so complex a process, and sleeplessness the resultant of so many different maladjustments, that it is, of course, possible that the woman may sleep well enough, even if she be deprived of the relief and pleasure of perfect union. But in so many married women sleeplessness and a consequent nervous condition are coupled with a lack of the complete sex-relation, that one of the first questions a physician

should

put to those of his women patients who are worn and sleepless is: Whether her husband really fulfills his marital duty in their physical relation.

W. F. ROBIE

SEX AND LIFE: WHAT THE EXPERIENCED SHOULD TEACH AND WHAT THE INEXPERIENCED SHOULD LEARN

, 1920

Writing boldly on sexual technique and satisfaction for both genders, Massachusetts physician Walter Franklin Robie (1866–1928) managed to get his book published by agreeing that it would be sold “only to members of the recognized professions.” But he and his publishers also put out pamphlets of separate chapters, so that doctors would be able to disseminate the information to their patients as well.

Robie slightly misquotes Shakespeare’s epic poem “Venus and Adonis.” The actual line is “Graze on my lips, and if those hills be dry . . .”

Young husband, . . . Don’t say much; but slowly and carefully feel your way. Your hands were made to use; your wife’s rounded form, her protuberances and depressions were largely made for hands and lips. The final act of love’s drama with the man and wife in mutual orgasm in love’s embrace, alone and without preliminaries, is like a banquet served on bare boards, without the accompaniments of light, heat, china, linen, silver, or conversation.

Kiss without shame, for she desires it, your wife’s lips, tongue, neck; and, as Shakespeare says: “If these founts be dry, stray lower where the pleasant fountains lie.” There is good instruction to young married people in good literature, but it is often unknown or ignored. Kiss her nipples, arms, and abdomen. Hold tenderly and manipulate softly her breasts, and delicately, when she yields nestlingly, caress her nipples.

. . . If her mind has not been freed from the ancient notion that a married woman should be cold and unresponsive toward her husband, gentleness and care and explanation will lead her to be properly responsive in time. Always remember this truth, that no woman lives who is so glacial that she will not respond to the tactful insistence of the right man. If you are sure that you are the right man at the time of marriage and do your part tenderly and faithfully, you need have no fears for the outcome.

LEWIS TERMAN

PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS IN MARITAL HAPPINESS

, 1938

For background on Terman, see

Happiness

.

It seems almost incredible that intercourse should be almost as frequent in the most unhappily mated couples as in the most happily mated, but such seems to be the case. One can only conclude that in this group sexual intercourse is to only a slight extent an expression of the sentiments of love and affection. It also bears little relation to the number of sexual complaints. . . . That is, spouses who claim that they have much to complain of with regard to the sexual unsatisfactoriness of their mates nevertheless have intercourse only a little less frequently than others.

A possible explanation of the unexpectedly high frequency of intercourse in unhappy marriages is that in such cases sex is the one type of communion between husband and wife which is mutually satisfying. “Any port in a storm,” as one of our friends has expressed it. Doubtless, too, there are marriages in which one of the mates consciously employs the stratagem of sexual enticement in the hope of reviving the waning affection of the other.

MARIE ROBINSON

THE POWER OF SEXUAL SURRENDER

, 1959

Though her book was a huge bestseller in a prefeminist age, American psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Marie Nyswander Robinson (1919–1986) was later excoriated for her support of traditional sex roles and her claim that, for women, “excitement comes from the act of surrender.”

A woman suffering from frigidity will be very relieved if her husband will make a gentle but blanket announcement to her that she is to drop her entire concern with orgasm until it happens. I have pointed out before that this indeed must be her working attitude before she has her first orgasmic experience. For a husband to affirm that this attitude is also his can be a great reassurance to her. She will then allow herself to really enjoy his “selfish” ecstasy without neurotically fixing on her own localized sensations. Indulging the deeply feminine role of

giving

pleasure can be more exciting to her than any other thing.

NENA O’NEILL AND GEORGE O’NEILL

OPEN MARRIAGE: A NEW LIFE STYLE FOR COUPLES

, 1972

For background on the O’Neills, see

Expectations

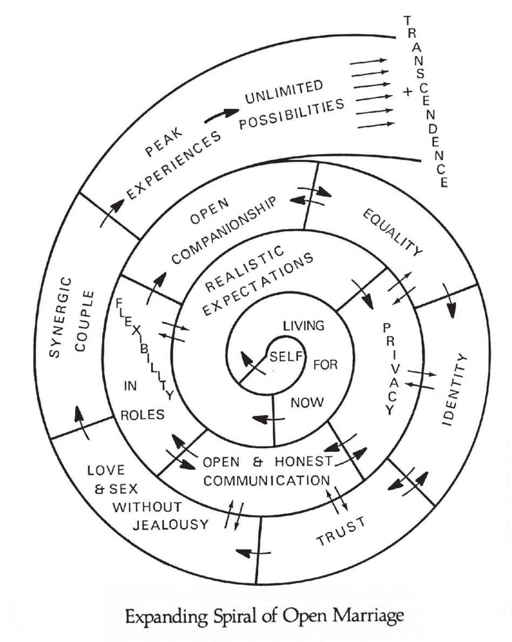

. The authors diagramed what they called “the expanding spiral of open marriage.” In its somewhat cryptic format, this spiral detailed the limitless possibilities inherent in open marriage. To clarify, however, the authors wrote: “We are not recommending outside sex, but we are not saying that it should be avoided, either. The choice is entirely up to you, and can be made only upon your own knowledge of the degree to which you have achieved, within your marriage, the trust, identity, and open communication necessary to the eradication of jealousy.”

ERICA JONG

FEAR OF FLYING

, 1973

In her first and most famous novel, Erica Jong (1942–) created a married protagonist, Isadora Wing, who sets out, despite her fear of flying, to pursue adventures both sexual and geographical. “This book,” the novelist Henry Miller correctly predicted at the time, “will make literary history.” To date, it has sold about twenty million copies worldwide, and the phrase defined in the excerpt below has endured as a slogan of female liberation.

I was not against marriage. I believed in it in fact. It was necessary to have one best friend in a hostile world, one person you’d be loyal to no matter what, one person who’d always be loyal to you. But what about all those other longings which after a while marriage did nothing much to appease? The restlessness, the hunger, the thump in the gut, the thump in the cunt, the longing to be filled up, to be fucked through every hole, the yearning for dry champagne and wet kisses, for the smell of peonies in a penthouse on a June night, for the light at the end of the pier in

Gatsby

. . . .

Five years of marriage had made me itchy for all those things: itchy for men, and itchy for solitude. Itchy for sex and itchy for the life of a recluse. I knew my itches were contradictory—and that made things even worse. I knew my itches were un-American—and that made things

still

worse. It is heresy in America to embrace any way of life except as half of a couple. Solitude is un-American. It may be condoned in a man—especially if he is a “glamorous bachelor” who “dates starlets” during a brief interval between marriages. But a woman is always presumed to be alone as a result of abandonment, not choice. And she is treated that way: as a pariah. There is simply no dignified way for a woman to live alone. Oh, she can get along financially perhaps (though not nearly as well as a man), but emotionally she is never left in peace. Her friends, her family, her fellow workers never let her forget that her husbandlessness, her childlessness—her

selfishness

, in short—is a reproach to the American way of life.

Even more to the point, the woman (unhappy though she knows her married friends to be) can never let

herself

alone. She lives as if she were constantly on the brink of some great fulfillment. As if she were waiting for Prince Charming to take her away “from all this.” All what? The solitude of living inside her own soul? The certainty of being herself instead of half of something else?

My response to all this was not (not yet) to have an affair and not (not yet) to hit the open road, but to evolve my fantasy of the Zipless Fuck. The zipless fuck was more than a fuck. It was

a platonic ideal. Zipless because when you came together zippers fell away like rose petals, underwear blew off in one breath like dandelion fluff. Tongues intertwined and turned liquid. Your whole soul flowed out through your tongue and into the mouth of your lover.

For the true, the ultimate zipless A-1 fuck, it was necessary that you never get to know the man very well. . . .

. . . The zipless fuck is absolutely pure. It is free of ulterior motives. There is no power game. The man is not “taking” and the woman is not “giving.” No one is attempting to cuckold a husband or humiliate a wife. No one is trying to prove anything or get anything out of anyone. The zipless fuck is the purest thing there is. And it is rarer than the unicorn. And I have never had one.

GAY TALESE

THY NEIGHBOR’S WIFE

, 1980

Gay Talese (1932–) first gained fame for practicing the genre-bending New Journalism, essentially employing the techniques of literary fiction to convey fact. Talese was rigorous, patient, and immersive in his reporting, whether revealing the workings of the Mafia in

Honor Thy Father

or exploring America’s secret sexual life in

Thy Neighbor’s Wife

. The book was a bombshell—popular with readers and controversial among critics, many of whom decried Talese’s explicitness as well as his participation in plenty of the behavior he was reporting. Central to the book was the narrative of Judith and John Bullaro, an LA couple who were drawn to visit Sandstone, the swingers’ retreat started by John Williamson and Barbara Cramer. In the scene below, Cramer explained the philosophy of marriage that she and her husband shared.

Talese’s marriage to the publisher Nan Talese passed the half-century mark in 2009.

In the room she hastily removed her clothes, and Bullaro saw again her remarkable body, and soon felt her aggressive touch as he lay naked on the bed and she mounted him. The ease with which she achieved her satisfaction, and the agile manner with which she pulled him on top of her without disengaging him, reminded him of a tumbling act in a circus, and confirmed as well that her marriage had neither altered her sportive style nor diminished her desire for supplementary sex.

After they had finished and were relaxing on the bed, Bullaro asked if she was happily married. She answered that she was, adding that her husband was the most remarkable man she had ever known; he was sensitive and self-assured and was not intimidated by her individuality.

In fact, she went on, he was encouraging her to become more independent than she was already, hoping that as she attained higher levels of fulfillment and self-awareness she would reinvest these assets into their marriage. A marriage should promote personal growth instead of limitations and restrictions, she went on, and as Bullaro listened with a certain cynicism he assumed that she was paraphrasing her husband. He had never heard her speak this way before, and while he was still bewildered by her husband’s motives, and pondered what her husband would do if he knew what had just transpired in this bedroom, he remained silent as Barbara Williamson continued to explain for his benefit, and perhaps for her own, the kind of marriage she now had.

Most married people, she said, had “ownership problems”: They wanted to totally possess their spouse, to expect monogamy, and if one partner admitted an infidelity to the other it would most likely be interpreted as a sign of a deteriorating marriage. But this was absurd, she said—a husband and wife should be able to enjoy sex with other people without threatening their primary relationship, or lying or feeling guilty about their extramarital experiences. People cannot expect all of their needs to be satisfied by a spouse, and Barbara said that her relationship with John Williamson was enhanced by their mutual respect for freedom, and they both felt sufficiently secure in their love to admit openly to one another that they sometimes made love to other people.

JOHN UPDIKE

RABBIT IS RICH

, 1981