The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World* (13 page)

Read The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World* Online

Authors: Nathaniel Philbrick

Tags: #Retail, #Ages 10+

âââ Thursday, January 11, was “a fair day.” Given the uncertainty of the weather, they knew they must make as much progress as possible on the housesâespecially since, it was still assumed, the

Mayflower

would soon be returning to England.

Mayflower

would soon be returning to England.

The frantic pace of the last two months was beginning to take its toll on William Bradford. He had suffered through a month of exposure to the freezing cold on the exploratory missions, and the stiffness in his ankles made it difficult to walk. But there was more troubling him than physical discomfort. Dorothy's passing had opened the floodgates: Death was everywhere.

That day, as Bradford worked beside the others, he was “vehemently taken with a grief and pain” that pierced him to his hipbone. He collapsed and was carried to the common house. At first it was feared Bradford might not last the night. But “in time through God's mercy,” he began to improve, even as illness continued to spread among them.

The common house soon became as “full of beds as they could lie one by another.” Like the Native Americans before them, the Pilgrims were struggling to survive on a hillside where death had become a way of life. In the days ahead, so many fell ill that there were barely half a dozen people left to tend the sick. Progress on the houses came to a standstill as the healthy ones became full-time nursesâpreparing meals, tending fires, washing the “loathsome clothes,” and emptying chamber pots. Bradford later singled out William Brewster and Miles standish as incredible sources of strength:

And yet the Lord so upheld these persons as in this general calamity they were not at all infected either with sickness or lameness. And what I have said of these I may say of many others who died in this general visitation, and others yet living; that whilst they had health, yea or any strength continuing, they were not wanting to any that had need of them. And I doubt not that their recompense is with the Lord.

â

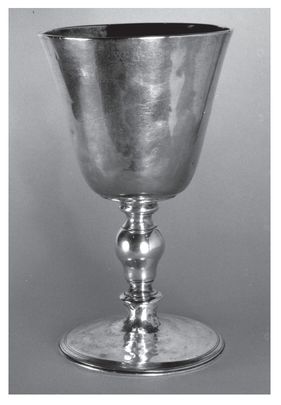

William Bradford's silver drinking cup, made in England in 1634.

William Bradford's silver drinking cup, made in England in 1634.

At one point, Bradford requested a small container of beer from the

Mayflower,

hoping that it might help in his recovery. With little left for the return voyage to England, the sailors responded that if Bradford “were their own father he should have none.” soon after, disease began to ravage the crew of the

Mayflower,

including many of their officers and “lustiest men.” Early on, the boatswain, “a proud young man,” according to Bradford, who would often “curse and scoff at the passengers,” grew ill. Despite his treatment of them, several of the Pilgrims attended to the young officer. In his final hours, the boatswain experienced a kind of deathbed conversion, crying out, “Oh, you, I now see, show your love like Christians indeed one to another, but we let one another die like dogs.” Master Jones also appears to have undergone a change of heart. soon after his own men began to fall ill, he let it be known that beer was now available to the Pilgrims, “though he drunk water homeward bound.”

Mayflower,

hoping that it might help in his recovery. With little left for the return voyage to England, the sailors responded that if Bradford “were their own father he should have none.” soon after, disease began to ravage the crew of the

Mayflower,

including many of their officers and “lustiest men.” Early on, the boatswain, “a proud young man,” according to Bradford, who would often “curse and scoff at the passengers,” grew ill. Despite his treatment of them, several of the Pilgrims attended to the young officer. In his final hours, the boatswain experienced a kind of deathbed conversion, crying out, “Oh, you, I now see, show your love like Christians indeed one to another, but we let one another die like dogs.” Master Jones also appears to have undergone a change of heart. soon after his own men began to fall ill, he let it be known that beer was now available to the Pilgrims, “though he drunk water homeward bound.”

Â

âââ On Friday, January 12, John Goodman and Peter Brown were cutting thatch for their roofs about a mile and a half from the settlement. They had with them the two dogs, a small spaniel and a huge mastiff. English mastiffs were frequently used in bearbaitingsâa savage sport popular in London in which a dog and a bear fought each other to the death. Mastiffs were also favored by English noblemen, who used them to catch poachers. The Pilgrims' mastiff appears to have been more of a guard dog brought to protect them against wild beasts and Indians.

That afternoon, Goodman and Brown paused from their labors for a midday snack, then took the two dogs for a short walk in the woods. Near the banks of a pond they saw a large deer, and the dogs took off in pursuit. By the time Goodman and Brown had caught up with the dogs, they were all thoroughly lost.

It began to rain, and by nightfall it was snowing. They had hoped to find an Indian wigwam for shelter but were forced, in Bradford's words, “to make the earth their bed, and the element their covering.” Then they heard what they took to be “two lions roaring exceedingly for a long time together.” These may have been eastern cougars, also known as mountain lions, a species that once ranged throughout most of North and south America. The cry of a cougar has been compared to the scream of a woman being murdered, and Goodman and Brown were now thoroughly terrified. They decided that if a lion should come after them, they would scramble into the limbs of a tree and leave the mastiff to do her best to defend them.

All that night they paced back and forth at the foot of a tree, trying to keep warm in the freezing darkness. They still had the sickles they had used to cut thatch, and with each wail of the cougars, they gripped the handles a little tighter. The mastiff wanted desperately to chase whatever was out there in the woods, so they took turns holding back the dog by her collar. At daybreak, they once again set out in search of the settlement.

After passing several streams and ponds, Goodman and Brown came upon a huge piece of open land that had recently been burned by the Indians. For centuries, the Indians had been burning the landscape on a seasonal basis, a form of land management that created surprisingly open forests, where a person might easily walk or even ride a horse amid the trees. Come summer, this five-mile-wide section of blackened ground would resemble, to a remarkable degree, the wide and rolling fields of their native England.

Not until the afternoon did Goodman and Brown find a hill that gave them a view of the harbor. Now that they were able to orient themselves, they were soon on their way back home. When they arrived that night, they were, according to Bradford, “ready to faint with travail and want of victuals, and almost famished with cold.” Goodman's frostbitten feet were so swollen that they had to cut away his shoes.

Â

âââ The final weeks of January were spent transporting goods from the

Mayflower

to shore. On sunday, February 4, yet another storm lashed Plymouth Harbor. The rain was so fierce that it washed the clay daubing from the sides of the houses, while the

Mayflower,

which was floating much higher in the water than usual after the removal of so much freight, wobbled dangerously in the wind.

Mayflower

to shore. On sunday, February 4, yet another storm lashed Plymouth Harbor. The rain was so fierce that it washed the clay daubing from the sides of the houses, while the

Mayflower,

which was floating much higher in the water than usual after the removal of so much freight, wobbled dangerously in the wind.

Tensions among the Pilgrims were high. With two, sometimes three people dying a day, there might not be a plantation left by the arrival of spring. Almost everyone had lost a loved one. Christopher Martin, the

Mayflower

's governor, had died in early January, soon to be followed by his wife, Mary. Three other familiesâthe Rigsdales, Tinkers, and Turnersâwere entirely wiped out, with more to follow. Thirteen-year-old Mary Chilton, whose father had died back in Provincetown Harbor, became an orphan when her mother passed away that winter. Other orphans included seventeen-year-old Joseph Rogers, twelve-year-old samuel Fuller, eighteen-year-old John Crackston, seventeen-year-old Priscilla Mullins, and thirteen-year-old Elizabeth Tilley (who also lost her aunt and uncle, Edward and Ann). By the middle of March, there were four widowers: William Bradford, Miles standish, Francis Eaton, and Isaac Allerton; Allerton was left with three surviving children between the ages of four and eight. With the death of her husband, William, susanna White, mother to the newborn Peregrine and five-yearold Resolved, became the plantation's only surviving widow. By the spring, 52 of the 102 who had originally arrived at Provincetown were dead.

Mayflower

's governor, had died in early January, soon to be followed by his wife, Mary. Three other familiesâthe Rigsdales, Tinkers, and Turnersâwere entirely wiped out, with more to follow. Thirteen-year-old Mary Chilton, whose father had died back in Provincetown Harbor, became an orphan when her mother passed away that winter. Other orphans included seventeen-year-old Joseph Rogers, twelve-year-old samuel Fuller, eighteen-year-old John Crackston, seventeen-year-old Priscilla Mullins, and thirteen-year-old Elizabeth Tilley (who also lost her aunt and uncle, Edward and Ann). By the middle of March, there were four widowers: William Bradford, Miles standish, Francis Eaton, and Isaac Allerton; Allerton was left with three surviving children between the ages of four and eight. With the death of her husband, William, susanna White, mother to the newborn Peregrine and five-yearold Resolved, became the plantation's only surviving widow. By the spring, 52 of the 102 who had originally arrived at Provincetown were dead.

â

The wicker cradle reputed to have been brought to America by William and Susanna White.

The wicker cradle reputed to have been brought to America by William and Susanna White.

And yet, amid all this tragedy, there were miraculous exceptions. The families of William Brewster, Francis Cook, stephen Hopkins, and John Billington were completely untouched by disease. The strangers Billington and Hopkins had a total of six living children among them, accounting for more than a fifth of the young people in the entire plantation. The future of Plymouth was beginning to look less like a separatist community of saints than a mix of both groups.

Even more worrisome than the emotional and physical strain of all this death was the growing fear of Indian attack. The Pilgrims knew that the Native inhabitants were watching them, but so far the Indians had refused to come forward. It was quite possible that they were simply waiting the Pilgrims out until there were not enough left to put up a fight. It became necessary, therefore, to make the best show of strength they could.

Whenever the alarm was sounded, the sick were pulled from their beds and propped up against trees with muskets in their hands. They would do little good in case of an actual attack, but at least they were out there to be counted. The Pilgrims also tried to conceal the fact that so many of them had died by secretly burying the dead at night. They did such a good job of hiding their loved ones' remains that it was not until more than a hundred years later, when a violent rainstorm washed away the topsoil and revealed some human bones, that the location of these hastily dug graves was finally identified.

Â

âââ On Friday, February 16, one of the Pilgrims was hidden in the reeds of a salt creek about a mile and a half from the plantation, hunting ducks. That afternoon, the duck hunter found himself closer to an Indian than any of them had so far come.

He was lying amid the cattails when a group of twelve Indians marched past him on the way to the settlement. In the woods behind him, he heard “the noise of many more.” Once the Indians had safely passed, he sprang to his feet and ran for the plantation to sound the alarm. Miles standish and Francis Cook were working in the woods when they heard the signal. They dropped their tools, ran down the hill, and armed themselves, but once again, the Indians never came. Later that day, when standish and Cook returned to get their tools, they discovered that they'd disappeared. That night, they saw “a great fire” near where the duck hunter had first spotted the Indians.

The next day, a meeting was called “for the establishing of military orders amongst ourselves.” Not surprisingly, Miles standish was officially named their captain. In the midst of the meeting, someone realized that two Indians were standing on the top of what became known as Watson's Hill on the other side of Town Brook, about a quarter mile to the south. The meeting immediately ended, and the men hurried to get their muskets. When the Pilgrims reassembled under the direction of their newly designated captain, the Indians were still standing on the hill.

The two groups stared at each other across the valley of Town Brook. The Indians gestured for them to approach. The Pilgrims, however, made it clear that they wanted the Indians to come to them. Finally, standish and stephen Hopkins, with only one musket between them, began to make their way across the brook. Before they started up the hill, they laid the musket down on the ground “in sign of peace.” But “the savages,” Bradford wrote, “would not tarry their coming.” They ran off to the shouts of “a great many more” hidden on the other side of the hill. The Pilgrims feared an assault might be imminent, “but no more came in fight.”

Other books

Agatha Raisin and the Witch of Wyckhadden by M. C Beaton

Starfish Prime (Blackfox Chronicles Book 2) by T.S. O'Neil

A Question of Ghosts by Cate Culpepper

The Portable Henry James by Henry James

Sanctuary Line by Jane Urquhart

Out Of Line by Jen McLaughlin

Levi's Blue: A Sexy Southern Romance by M. Leighton

The Doctor's Choice by J. D. Faver

The Circle Eight: Nicholas by Lang, Emma

Desire & Ice: A MacKenzie Family Novella (The MacKenzie Family) by Christopher Rice