The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World* (41 page)

Read The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World* Online

Authors: Nathaniel Philbrick

Tags: #Retail, #Ages 10+

Alderman and Cook rushed over to Church and told him that they had just killed Philip. He ordered them to keep the news a secret until the battle was over. The fighting continued for a few more minutes, but finding a gap in the English line on the west end of the swamp, most of the enemy, now led by Annawon, escaped.

Church gathered his men on the hill where the Indians' shelter had been built and told them of Philip's death. The army, Indians and English alike, shouted “huzzah!” three times. Taking hold of the sachem's breeches and stockings, the sakonnets dragged his body through the mud and dumped him beside the shelterâ“a doleful, great, naked, dirty beast,” Church remembered.

â

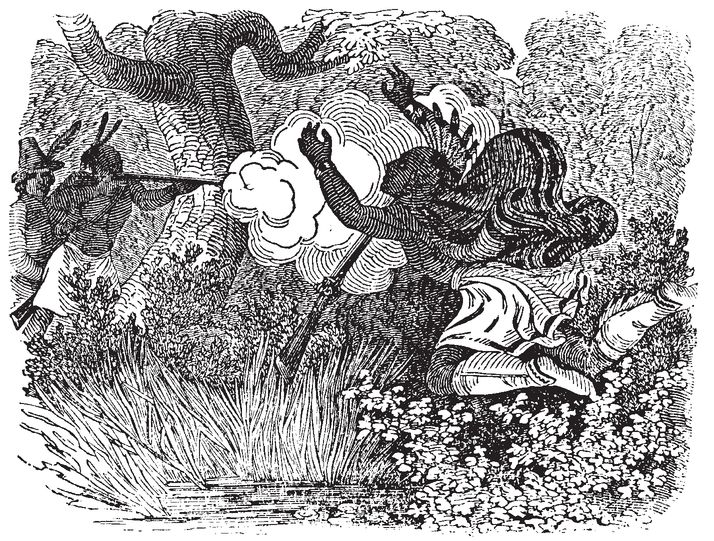

A nineteenth-century engraving of King Philip's death from a shot fired by a Pocasset Indian.

A nineteenth-century engraving of King Philip's death from a shot fired by a Pocasset Indian.

With his men around him and with Philip's mud-smeared body at his feet, Church declared, “That for as much as he had caused many an Englishman's body to lie unburied and rot above ground, that not one of his bones should be buried.” He called forward a sakonnet who had already executed several of the enemy and ordered him to draw and quarter the body of King Philip.

soon the body had been divided into four pieces. One of Philip's hands had a distinctive scar caused by an exploded pistol. Church awarded the hand to Alderman, who later placed it in a bottle of rum and made “many a penny” in the years to come by showing the hand to curious New Englanders.

Â

âââ On Thursday, August 17, Plymouth Pastor John Cotton led his congregation in a day of Thanksgiving. soon after the end of public worship that day, Benjamin Church and his men arrived with the biggest trophy of the war. “[Philip's] head was brought into Plymouth in great triumph,” the church record states, “he being slain two or three days before, so that in the day of our praises our eyes saw the salvation of God.”

The head was placed on one of the palisades of the town's one-hundred-foot-square fort, built near where, back in 1623, Miles standish had placed the head of Wituwamat after his victory at Wessagussett. Philip's head would remain in Plymouth for more than two decades, becoming the town's most famous sight long before anyone took notice of the hunk of granite known as Plymouth Rock.

Â

âââ Philip was dead, but Annawon, the sachem's “chief captain,” was still out there. Old as Annawon was, the colony would not be safe, Governor Winslow insisted, until he had been taken. There was yet another well-known warrior still at large: Tuspaquin, the famed Black sachem of Nemasket.

Church was expected to hunt down and kill these two warriors, but he had other ideas. He had recently been contacted by Massachusetts Bay about helping the colony against the Abenakis in Maine, where fighting still raged. With Tuspaquin and Annawon at his side, Church believed, he might be able to beat the mighty Abenakis.

On August 29, he learned that the Black sachem was in Lakenham, about six miles west of Plymouth. But after two days of searching, he'd only managed to take Tuspaquin's wife and children. He left a message for the sachem with two old Nemasket women that Tuspaquin “should be his captain over his Indians if he [proved to be] so stout a man as they reported him to be.” With luck, Tuspaquin would turn himself in at Plymouth, and Church would have a new Native officer.

About a week later, word came from Taunton that Annawon and his men had been seen at Mount Hope. On Thursday, september 7, Church and just five Englishmen, including his trusted lieutenant Jabez Howland, and twenty Indians left Plymouth to hunt for Annawon.

They searched Mount Hope for several days and captured a large number of Indians. One of the captives reported that his father and a girl had just come from Annawon's headquarters. The old man and the girl were hidden in a nearby swamp, and the Indian offered to take Church to them. Leaving Howland and most of the company with the prisoners, Church and a handful of men went in search of the prisoner's father.

That afternoon they found the old man and the girl, each of whom was carrying a basket of food. They said that Annawon and about fifty to sixty men were at squannakonk swamp, several miles to the north between Taunton and Rehoboth. If they left immediately, they could be there by sundown. The old man and the girl walked so quickly over the swampy ground that Church and the rest of the company had difficulty keeping up. The old man insisted that since Church had spared his life, he had no choice but to serve him, and if Church's plan was to work, they needed to get there as quickly as possible.

By the time they reached Annawon's camp, it was almost completely dark. Annawon, the old man explained, had set up camp at the base of a steep rock, and the surrounding swamp prevented entry from any other point. In the gathering darkness, Church and the old man crept up to the edge of the rock. They could see the fires of Annawon's people. There were three different groups, with “the great Annawon” and his son and several others sitting nearest the rock. Their food was cooking on the fires, and Church noticed that their guns were leaning together against a branch with a mat placed over the weapons to keep them from getting wet. He also noticed that Annawon's feet and his son's head were almost touching the muskets.

â

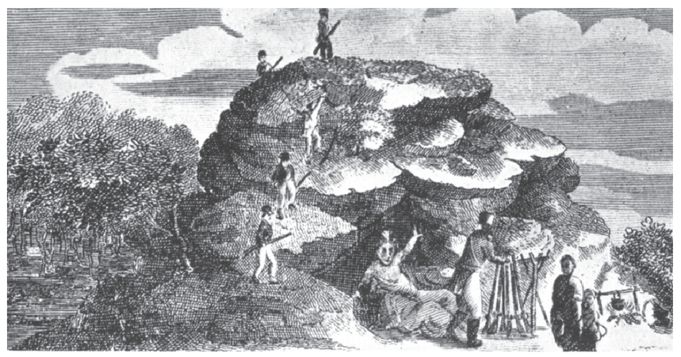

A nineteenth-century engraving depicting Church's capture of Annawon.

A nineteenth-century engraving depicting Church's capture of Annawon.

No one in his right mind would dare climb down from the rock to enter Annawon's camp. But if Church could hide himself behind his two Indian guides, who were known to Annawon and his warriors, he might be able to grab the Indians' guns before they realized who he was.

With the two guides leading the way, Church and his men climbed down the rock face, sometimes grasping bushes to keep from falling down the steep descent and using the noise of women grinding corn to hide the sounds of their approach. As soon as he reached the ground, Church walked over to the guns with his hatchet in his hand. seeing who it was, Annawon's son pulled his blanket over his head and “shrunk up in a heap.” Annawon leaped to his feet and cried out “howoh?” or “who?” Realizing that the Englishman could easily kill his son, Annawon sadly surrendered.

Now that he had captured Annawon, Church sent the sakonnets to the other campsites to inform the Indians that their leader had been taken and that Church and “his great army” would grant them mercy if they gave up quietly. As it turned out, many of the enemy were related to the sakonnets and were more than willing to believe them. soon, Church and his company of half a dozen men had won a complete and bloodless surrender.

Church then turned to Annawon and through an interpreter asked what he had to eatâ“for,” he said, “I am come to sup with you.” In a booming voice, Annawon replied, “taubut,” or “it is good.” sprinkling some of the salt that he carried with him in his pocket on the meat, Church enjoyed some roasted beef and ground green corn. Once the meal had been completed, he told Annawon that as long as his people cooperated they would all be allowed to live, except perhaps Annawon himself, whose fate must be decided by the Plymouth courts.

As the meal came to an end, Church realized he desperately needed sleep. He'd been awake now for two days straight. He told his men that if they let him sleep for two hours, he would keep watch for the rest of the night. But as soon as he lay down for a nap, he discovered that he was once again wide awake. After an hour or so, he looked up and saw that everyone else was fast asleep, with one exception: Annawon.

For another hour, they lay on opposite sides of the fire “looking one upon the other.” since Church did not know the Indians' language, and, he assumed, Annawon did not know English, neither one of them had anything to say. suddenly the old warrior threw off his blanket and walked off into the darkness. Church assumed he had left to relieve himself, but when Annawon did not return for several minutes, Church feared he might be up to no good. Church moved next to Annawon's son. If his father should attempt to attack him, he would use the young man as a hostage.

A full moon had risen, and in the ghostly silver light, he saw Annawon approaching with something in his hands. The Indian came up to Church and dropped to his knees. Holding up a woven basket, he said in perfect English, “Great Captain, you have killed Philip and conquered his country, for I believe that I and my company are the last that war against the English, so [I] suppose the war is ended by your means and therefore these things belong unto you.”

Inside the basket were several belts of wampum. One was nine inches wide and showed a picture of flowers, birds, and animals. Church was now standing, and when Annawon draped the belt over his shoulders, it reached down to his ankles. The next belt was one that Philip had often wrapped around his head and had streamers that had hung at his back; the third was meant for his chest and had a star at either end. There were also two powder horns and a rich red blanket. These, Annawon explained, were what Philip “was wont to adorn himself with when he sat in state.”

The two warriors talked late into the night. Annawon spoke with particular fondness of his service under Philip's father, Massasoit, and “what mighty success he had formerly in wars against many nations of Indians.” They also spoke of Philip. Annawon blamed the war on two factors: the lies of the Praying Indians, especially John sassamon, and the young warriors, whom he compared to “sticks laid on a heap, till by the multitude of them a great fire came to be kindled.”

At daybreak, Church marched his prisoners to Taunton, where he met up with Lieutenant Howland, “who expressed a great deal of joy to see him again and said 'twas more than ever he expected.” The next day, Church sent Howland with the majority of the prisoners to Plymouth. In the meantime, he wanted Annawon to meet his friends in Rhode Island. They remained in Newport for several days and then finally left for Plymouth.

In just two months' time, Church had brought in a total of seven hundred Indians. Given his efforts toward ending the war, he hoped that Governor Winslow might listen to his pleas that Annawon and, if he should turn himself in, Tuspaquin be granted mercy.

Massachusetts governor John Leverett had requested to meet with him to discuss again the possibility of his leading a company in Maine, and Church quickly left for Boston. But when he returned to Plymouth a few days later, he discovered “to his grief” that the heads of both Annawon and Tuspaquin had joined Philip's on the palisades of Fort Hill.

Â

âââ In september of 1676, fifty-six years after the sailing of the

Mayflower

and a month after the death of Philip, a ship named the

Seaflower

left from the shores of New England. Like the

Mayflower,

she carried a human cargo. But instead of 102 colonists, the

Seaflower

was bound for Jamaica with 180 Native American slaves.

Mayflower

and a month after the death of Philip, a ship named the

Seaflower

left from the shores of New England. Like the

Mayflower,

she carried a human cargo. But instead of 102 colonists, the

Seaflower

was bound for Jamaica with 180 Native American slaves.

More than a thousand Indians were sold into slavery during King Philip's War, with over half the slaves coming from Plymouth Colony alone. But by september 1676, plantation owners in the Caribbean had decided that they did not want slaves who had already shown a willingness to revolt. We don't know what happened to the Indians aboard the

Seaflower,

but we do know that the captain of one American slave ship was forced to venture all the way to Africa before he finally sold his cargo. And so, fifty-six years after the sailing of the

Mayflower,

a vessel from New England completed a voyage of a different sort.

Seaflower,

but we do know that the captain of one American slave ship was forced to venture all the way to Africa before he finally sold his cargo. And so, fifty-six years after the sailing of the

Mayflower,

a vessel from New England completed a voyage of a different sort.

EPILOGUE

The Rock

Other books

Love in All the Right Places (Chick Lit bundle) by Mariano, Chris, Llanera, Agay, Peria, Chrissie

The Rape of Venice by Dennis Wheatley

A Book of Five Rings by Miyamoto Musashi

A London Season by Anthea Bell

Sex in the Hood Saga by White Chocolate

Bare Nerve by Katherine Garbera

Women & Other Animals by Bonnie Jo. Campbell

State We're In by Parks, Adele

Circles of Seven by Bryan Davis

Fatal Reaction by Hartzmark, Gini