The Men Who Stare at Goats (22 page)

Read The Men Who Stare at Goats Online

Authors: Jon Ronson

I e-mailed Colonel Alexander to ask if he was indeed advocating the use of some kind of mind-control machine and he replied, somewhat ruefully, and a little guardedly: “If we do go to scrambling minds, then the whole mind-control conspiracy issues arise.”

What he meant was, MK-ULTRA.

It was really just about the worst PR the U.S. intelligence services had ever suffered, certainly until the Abu Ghraib photographs came along in 2004. Jim Channon might have pretty much single-handedly invented the idea of the army thinking outside the box (as one of his admirers had once told me), but the CIA had been there before him.

Everyone was still bruised over MK-ULTRA.

There is a house in Frederick, Maryland, that has barely been touched since 1953. It looks like an exhibit in a down-at-heels museum of the Cold War. All that brightly colored Formica and the kitschy kitchen ornaments—breezy symbols of 1950s American optimism—haven’t stood the test of time.

Eric Olson’s house—and Eric would be the first to admit this—could do with some redecoration.

Eric was born there, but he never liked Frederick and he never liked the house. He got out as quickly as he could after high school and ended up in Ohio and India and New York and Massachusetts, back in Frederick and Stockholm and California, but in 1993 he thought he would just crash out for a few months, and then ten years passed, during which time he hasn’t decorated for three reasons:

1. He hasn’t any money.

2. His mind is on other things.

3. And, really, his life ground to a shuddering halt on November 28, 1953, and if your living environment is

meant to reflect your inner life, Eric’s house does the job. It is an inescapable reminder of the moment Eric’s life froze. Eric says that if he ever forgets “why I’m doing this,” he just needs to look around his house, and 1953 comes flooding back to him.

Eric says 1953 was probably the most significant year in modern history. He says we’re all stuck in 1953, in a sense, because the events of that year have a continual and overwhelming impact on our lives. He rattled through a list of key events that occurred in 1953. Everest was conquered. James Watson and Francis Crick published, in

Nature

magazine, their famous paper mapping the double helix structure of DNA. Elvis first visited a recording studio, and Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” gave the world rock and roll, and, subsequently, the teenager. President Truman announced that the United States had developed a hydrogen bomb. The polio vaccine was created, as was the color TV. And Allen Dulles, the director of the CIA, gave a talk to his Princeton alumni group in which he said, “Mind warfare is the great battlefield of the Cold War, and we have to do whatever it takes to win this.”

On the night of November 28, 1953, Eric went to bed, as normal, a happy nine-year-old child. The family home had been built three years earlier, and his father, Frank, was still putting the finishing touches to it, but now he was in New York on business. Eric’s mother, Alice, was sleeping down the hall. His little brother, Nils, and his sister, Lisa, were in the next room.

And then, somewhere around dawn, Eric was woken up.

“It was a very dim November predawn,” Eric said.

Eric was woken up by his mother and taken down the hall, still wearing his pajamas, toward the living room—the same room where the two of us now sat, on the same sofas.

Eric turned the corner to see the family doctor sitting there.

“And,” Eric said, “also, there were these two …” Eric searched for a moment for the right word to describe the others. He said, “There were these two … men … there also.”

The news that the men delivered was that Eric’s father was dead.

“What are you

talking

about?” Eric asked them, crossly.

“He had an accident,” said one of the men, “and the accident was that he fell or jumped out of a window.”

“Excuse me?” said Eric. “He did

what

?”

“He fell or jumped out of a window in New York.”

“What does that

look

like?” asked Eric.

This question was greeted with silence. Eric looked over at his mother and saw that she was frozen and empty-eyed.

“How do you fall out of a window?” said Eric. “What does that mean? Why would he do that? What do you mean: fell or jumped?”

“We don’t know if he fell,” said one of the men. “He might have fallen. He might have jumped.”

“Did he

dive

?” asked Eric.

“Anyhow,” said one of the men, “it was an accident.”

“Was he standing on a

ledge

and he jumped?” asked Eric.

“It was a work-related accident,” said one of the men.

“Excuse me?” said Eric. “He fell out a window and that’s

work

related? What?”

Eric turned to his mother.

“Um,” he said. “What is his work again?”

Eric believed his father was a civilian scientist, working with chemicals at the nearby Fort Detrick military base.

Eric said to me, “It very quickly became an incredibly rancorous issue in the family because I was always the kid saying, ‘Excuse me, where did he

go

? Tell me this story again.’ And my mother very quickly adopted the stance, ‘Look, I’ve told you this story a

thousand

times.’ And I would say, ‘Yeah, but I don’t get it.’”

Eric’s mother had created—from the same scant facts offered to Eric—this scenario: Frank Olson was in New York. He was staying on the tenth floor of the Statler Hotel, now the Pennsylvania Hotel, across the road from Madison Square Garden, in midtown Manhattan. He had a bad dream. He woke up confused, and headed in the dark toward the bathroom. He became disorientated and fell out of the window.

It was 2:00

A.M.

Eric and his little brother, Nils, told their school friends that their father had died of a “fatal nervous breakdown” although they had no idea what that meant.

Fort Detrick was what glued the town together. All their friends’ fathers worked at the base. The Olsons still got invited to neighborhood picnics and other community events, but there didn’t seem any reason for them to be there anymore.

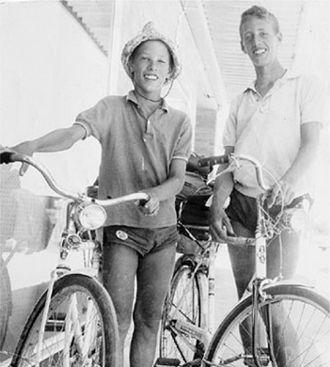

When Eric was sixteen, he and Nils, then twelve, decided to cycle from the end of their driveway to San Francisco. Even at that young age, Eric saw the 2,415-mile journey as a metaphor. He wanted to immerse himself in unknown American terrain, the mysterious America that had, for some

impenetrable reason, taken his father away from him. He and Nils would “reach the goal”—San Francisco—“by small continuous increments of motion along a single strand.” This was in Eric’s mind a test run for another goal he would one day reach in an equally fastidious way: the solution to the mystery of what happened to his father in that hotel room in New York at 2:00

A.M

.

I spent a lot of time at Eric’s house, reading his documents and looking though his photos and watching his home movies. There were pictures of the teenage Eric and his younger brother, Nils, standing by their bikes. Eric had captioned the photograph “Happy Bikers.” There were 8-mm films shot in the 1940s and early 1950s of Eric’s father, Frank, playing with the children in the garden. Then there were some films Frank Olson had shot himself during a trip he made to Europe a few months before he died. There was Big Ben and Changing the Guard. There was the Brandenberg Gate in Berlin. There was the Eiffel Tower. It looked like a family holiday, except the family wasn’t with him. Sometimes, in these 8-mm films, you catch a glimpse of Frank’s traveling companions, three men, wearing long dark coats and trilby hats, sitting in Parisian pavement cafés, watching the girls go by.

I watched them, and then I watched a home movie that a friend of Eric’s had shot on June 2, 1994, the day Eric had his father’s body exhumed.

There was the digger breaking through the soil.

There was a local journalist asking Eric, as the coffin was hauled noisily into the back of a truck, “Are you having second thoughts about this, Eric?”

She had to yell over the sound of the digger.

“Ha!” Eric replied.

“I keep expecting you to change your mind,” shouted the journalist.

Then there was Frank Olson himself, shriveled and brown on a slab in a pathologist’s lab at Georgetown University, Washington, his leg broken, a big hole in his skull.

And then, in this home video, Eric was back at home, exhilarated, talking on the phone to Nils: “I saw Daddy today!”

After Eric put the phone down he told his friend with the video camera the story of the bicycle trip he and Nils had taken in 1961, from the bottom of their driveway all the way to San Francisco.

“I’d seen an article in

Boys’ Life

about a fourteen-year-old kid who cycled from Connecticut to the West Coast,” Eric said, “so I figured my brother was twelve and I was sixteen and that averaged out at fourteen, so we could do it. We got these terrible heavy two-speed twin bikes, and we started off right here. Forty West. We heard it went all the way! And we made it! We went all the way!”

“No!” said Eric’s friend.

“Yeah,” said Eric. “We cycled across the country.”

“No way!”

“It’s an incredible story,” said Eric. “And we’ve never heard of a younger person than my brother who cycled across the United States. It’s doubtful there is one. When you think about it, twelve, and alone. It took us seven weeks, and we had unbelievable adventures all the way.”

“Did you camp out?”

“We camped out. Farmers would invite us to stay in their houses. In Kansas City the police picked us up, figuring we were runaways, and when they found out we weren’t they let us stay in their jail.”

“And your mom let you do this?”

“Yeah, that’s a kind of unbelievable mystery.”

(Eric’s mother, Alice, had died by 1994. She had been drinking on the quiet since the 1960s, and had begun locking herself in the bathroom and coming out mean and confused. Eric would never have exhumed his father’s remains while she was alive. His sister, Lisa, had died too, together with her husband and their two-year-old son. They’d been flying to the Adirondacks, where they were going to invest money in a lumber mill. The plane crashed, and everyone on board was killed.)

“Yeah,” said Eric, “it’s an unbelievable mystery that my mother let us go, but we called home twice a week from different places, and the local paper, the Frederick paper, twice a week had these front-page articles like

Olsons Reach St. Louis!

All across the country back then there were billboards advertising a place called Harold’s Club, which was a big gambling casino in Reno. It used to be the biggest casino in the world. And their motif was

HAROLD’S CLUB OR BUST!

Every day we’d see these billboards:

HAROLD’S CLUB OR BUST!

It became a kind of slogan for our journey. When we got to Reno we realized we couldn’t get into Harold’s Club because we were too young. So we decided to make a sign that said

HAROLD’S CLUB OR BUST!

and tie it to the back of our bikes, go over to Harold’s Club, and tell Harold, whoever he might be, that we’d carried this across the whole United States and we

were just crazy to see Harold’s Club. So we went into a drugstore. We got an old cardboard box and bought some crayons, and we started writing this sign. The woman who sold us the crayons said, “What are you guys doing?”

“We said, ‘We’re going to make a sign,

HAROLD’S CLUB OR BUST!

and tell Harold that we cycled all the way from …”

“She said, ‘These people are very smart. They’re not going to fall for this.’

“So we made this thing, took it out onto the streets, scuffed it up, tied it to the back of our bikes, went over to Harold’s Club, got to this big entryway—Harold’s Club was this gigantic thing, literally the biggest gambling casino in the world—and there was a doorperson there.

“He said, ‘What do you boys want?’

“We said, ‘We want to meet Harold.’

“He said, ‘Harold is not here.’

“We said, ‘Well, who

is

here?’

“He said, ‘Harold senior is not here but Harold junior is here.’

“We said, ‘That’s fine, we’ll take Harold junior.’

“He said, ‘Okay, I’ll go in and see.’

“Pretty soon out strides this dude in a fancy cowboy suit. Handsome guy. So he comes out and looks at our bikes and he says, ‘What are you guys doing?’

“We said, ‘Harold. We’ve been cycling across the United States and we’ve wanted to see Harold’s Club the whole time. We’ve been sweating across the desert.’

“And he said, ‘Well,

come on in

!’

“We ended up staying for a week at Harold’s Club. He took us up in a helicopter around Reno, put us up in a fancy hotel.

And when we were leaving he said, ‘I guess you guys want to see Disneyland, right? Well, let me call up my friend Walt!’

“So he called up Walt Disney—and this is one of the great disappointments of my life—Walt wasn’t home.”

I have wondered why Eric spent the evening of the day he had his father’s body exhumed telling his friend the story of Harold’s Club or Bust. Maybe it’s because Eric had spent so much of his adult life failing to be offered the kindness of strangers, failing to benefit from anything approaching an

American dream, but now Frank Olson was out there, lying on a slab in a pathologist’s lab, and perhaps things were about to turn around for Eric. Maybe some mysterious Harold Junior would come along and kindly explain everything.