The Men Who Stare at Goats (7 page)

Read The Men Who Stare at Goats Online

Authors: Jon Ronson

Colonel Alexander has been a special adviser to the Pentagon, the CIA, the Los Alamos National Laboratory, and NATO. He is also one of Al Gore’s oldest friends. He is not completely retired from the military. A week after I met him, he flew to Afghanistan for four months to act as a “special adviser.” When I asked him who he was advising and on what, he wouldn’t tell me.

For much of the afternoon, instead, John reminisced about the First Earth Battalion. His face broke into a broad smile when he recalled the secret late-night rituals that he and some fellow colonels would enact on military bases, after reading Jim’s manual.

“Big bonfires!” he said. “And guys with snakes on their heads!”

He laughed.

“Have you heard of Ron?” I asked him.

“Ron?” said Colonel Alexander.

“Ron who reactivated Uri,” I said.

Colonel Alexander fell silent. I waited for him to respond. After about thirty seconds, I realized that he wasn’t going to say another word until I asked him a different question. So I did.

“So did Michael Echanis really kill a goat just by staring at it?” I asked.

“Michael Echanis?” he said. He looked perplexed. “I think you’re talking about Guy Savelli.”

“Guy Savelli?” I asked.

“Yes,” said the colonel. “The man who killed the goat was definitely Guy Savelli.”

The Savelli Dance and Martial Arts Studio stands around the corner from a Red Lobster, a TGI Friday’s, a Burger King, and a Texaco garage, in the suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio. The sign on the door advertises lessons in ballet, tap, jazz, hiphop, aerobatics, pointe, kickboxing, and self-defense.

I had telephoned Guy Savelli a few weeks earlier. I told him who I was and asked if he might describe the work he had undertaken inside Goat Lab. Colonel Alexander had told me that Guy was a civilian. He was under no military contract. So it seemed possible that he might talk. But instead there was a very long silence.

“Who are you?” he finally asked.

I told him again. Then I heard a profoundly sad sigh. It was something more than “Oh no, not a journalist.” It sounded almost like a howl against the inescapable and unjust forces of destiny.

“Have I called at a bad time?” I asked him.

“No.”

“So

were

you at Goat Lab?” I asked.

“Yes.” He sighed again. “And yes, I

did

drop a goat when I was there.”

“I don’t suppose you still practice the technique?” I asked him.

“Yes, I do,” he said.

Guy fell silent again. And then he said—and his voice sounded sorrowful and distressed—“Last week I killed my hamster.”

“Just by staring at it?” I asked.

“Yes,” confirmed Guy.

Guy was a little more relaxed in the flesh, but not much. We met in the foyer of his dance studio. He is a grandfather now, but still jumpy and full of energy, moving around the room as if possessed. He was surrounded by some of his children and grandchildren, and half a dozen of his

Kun Tao

students stood anxiously around the edges of the studio. Something was up, that was clear, but I didn’t know what.

“So you did this to your hamster?” I asked Guy.

“Huh?” he said.

“Hamsters,” I said, suddenly unsure of myself.

“Yes,” he said. “They …” A look of bewilderment crossed his face. “When I do it,” he said, “the hamsters

die.”

“Really?” I asked.

“Hamsters drive me nuts,” said Guy. He began talking very fast. “They just go around and around. I wanted to stop it from going around and around. I thought,

I’m going to make it sick so it’ll burrow under the sawdust or something

.”

“But instead you made it die?”

“I’ve got it on tape!” said Guy. “I taped it. You can watch

the tape.” He paused. “I had a guy take care of the hamster every night.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Feed it. Water it.”

“So you knew it was a healthy hamster,” I said.

“Yes,” said Guy.

“And then you started staring,” I said.

“Three days,” sighed Guy.

“You must hate hamsters,” I said.

“It’s not that I

want

to do that to hamsters,” Guy explained. “But supposedly, if you’re a

master,

you should be able to do that kind of stuff. Is life just a punch and a kick and that’s it? Or is there more to it than that?”

Guy jumped in his car and went off to find his home video of the hamster being stared to death. While he was gone, his children, Bradley and Juliette, set up a video camera and began to film me.

“Why are you doing that?” I asked them.

There was a silence.

“Ask Dad,” said Juliette.

Guy returned an hour later. He was carrying a sheaf of papers and photographs along with a couple of video cassettes.

“Oh, I see Bradley has set up the camera,” he said. “Don’t worry about that! We film everything. You don’t mind, do you?”

Guy put the tape into the VCR, and he and I began to watch.

The video showed two hamsters in a cage. Guy explained to me that he was staring at one, trying to make it sick and visibly paranoid about its wheel, while the other was to

remain throughout an unstared-at control hamster. Twenty minutes passed.

“I’ve never known a hamster,” I said, “so I—”

“Bradley!” interrupted Guy. “You ever own a hamster?”

“Yes,” replied Bradley.

“You ever see one do

that

before?”

Bradley came into the room and watched the video for a moment.

“Never,” he said.

“Look at the way it’s glaring at the wheel!” said Guy.

The target hamster did indeed seem suddenly mistrustful of its wheel. It sat at the far end of the cage, looking at it warily.

“Usually that hamster

loves

its wheel,” explained Guy.

“It does seem odd,” I said, “although I have to say that emotions such as circumspection and wariness are not that easy to discern in hamsters.”

“Yeah, yeah,” said Guy.

“There will be some people reading this who own hamsters,” I said.

“Good,” said Guy. “Then they’ll know how

rare

that is. Your hamster people will know that.”

“My hamster-owning readers,” I agreed, “will know whether or not this is aberrant behavior… . He’s down!” I said.

The hamster had fallen. Its legs were in the air.

“I’m accomplishing the task I wanted to do,” said Guy. “Look! The other one has run right over it! He’s right on top of the other hamster! That’s bizarre! That’s kind of nuts, isn’t it? He’s not moving! I’m accomplishing my task right there.”

The other hamster fell over.

“You’ve dropped

both

hamsters!” I said.

“No, the other one has just fallen over,” explained Guy.

“Okay,” I said.

There was a silence.

“Is he dead now?” I asked.

“It gets more bizarre in a minute,” said Guy. He seemed to be dodging the question.

“Now!

It’s more bizarre now!”

The hamster was motionless. And it remained that way—utterly immobile—for fifteen minutes. Then it shook itself down and began eating again.

And then the tape ended.

“Guy,” I said. “I don’t know what to make of this. The hamster

did

seem to be behaving unusually in comparison with the control hamster, but on the other hand it definitely didn’t die. I thought you said I was going to watch it die.”

There was a short silence.

“My wife said, ‘No,’” he explained. “Back at the house. She said, ‘You don’t know if this guy’s a bleeding-heart liberal.’ She said, ‘Don’t show him the hamster

dying.

Don’t show him that. Show him the tape where the hamster acts bizarre instead.’”

Guy told me that what I had just seen were the edited highlights of two continuous days of staring. It was on the third day, Guy said, that the hamster dropped dead.

“I am a ghost,” said Guy.

We were in the foyer of his dance studio, standing underneath the bulletin board. It was covered with mementos of Savelli family successes. Jennifer Savelli, Guy’s daughter, danced with Richard Gere in

Chicago.

She danced in the seventy-fifth Academy Awards. But there was nothing much

on the wall about Guy—no newspaper cuttings or anything like that.

“You would never have known about me if Colonel Alexander hadn’t told you my name,” he said.

It was true. All I could find about Guy in the newspapers was the odd notice from the Cleveland Plain Dealer concerning awards won by his students in local tournaments. This other side of his life was entirely unchronicled.

Guy riffled through the papers and the photographs.

“Look!” he said. “Look at this!”

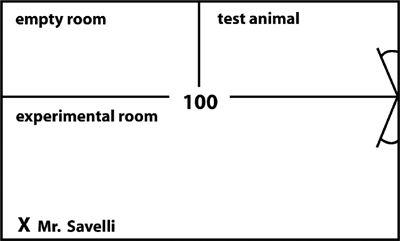

He handed me a diagram.

“Guy,” I said. “Is this Goat Lab?”

“Yes,” said Guy.

Bradley silently filmed me studying the Goat Lab diagram. Then Guy dropped the papers and the photographs. They scattered all over the floor. We both bent down to pick the stuff up.

“Oh,” murmured Guy. “You weren’t supposed to see

that

.”

I quickly looked over. In the moments before Guy hid it between some documents, I caught a glimpse of what I wasn’t supposed to see.

“Bloody hell,” I said.

“Right,” said Guy.

It was a blurry snapshot of a soldier crouched in a frosty field next to a fence. The photograph appeared to have captured the soldier in the act of karate chopping a goat to death.

“Jesus,” I said.

“You really weren’t supposed to see that,” said Guy.

Guy’s story began with a telephone call he received, out of the blue, in the summer of 1983.

“Mr. Savelli?” said a voice. “I’m phoning from Special Forces.”

It was Colonel Alexander.

Guy was not a military man. Why were they calling him? The colonel explained that since their last martial arts teacher, Michael Echanis, had died in Nicaragua back in 1978, Special Forces had basically stopped incorporating those kinds of techniques into their training programs down at Fort Bragg, but they were ready to give them another try. They had chosen him, he explained, because the branch of martial arts he practices—Kun Tao—has a uniquely mystical dimension. Guy teaches his students that “only with total integration of the mental, physical, and spiritual can one hope to come away unscathed. Our intention is to teach this integrated way and show others how to have exceptional

paranormal results that are usually associated with fables for the young.”

The colonel asked Guy if he could come down to Fort Bragg for a week or so, to test the waters. Could he step into Michael Echanis’s shoes? Guy said he’d give it a try.

On the first day, Guy taught the soldiers how to break slabs of concrete with their bare hands, how to withstand being whacked on the back of the neck with a thick metal rod, and how to make a person forget what he is about to say.

“How do you make a person forget what he’s about to say?” I asked Guy.

“Easy,” he said. “You just do this—” Guy scrunched up his face and yelled, “Noooooooo!”

“Really?” I asked.

“You ever play pool and you miss your shot and you want your opponent to miss his shot and you go, ‘Noooooooo’? And then they miss

their

shot! It’s the same thing.”

“Is it all in the tone of voice?” I asked.

“You say it

inside

your head,” said Guy, exasperated. “You get that

feeling

inside of you.”

And so it was, on the evening of the first day, that Special Forces mentioned to Guy that they had goats. Guy said he couldn’t remember who steered the conversation then, but he did recall, at some point during the evening, announcing, “Let’s give it a try.”

“So the next morning,” Guy said, “they got a goat, they set it up, and we started.”

As Guy recounted this story, the atmosphere inside the dance studio remained apprehensive. Bradley continued to film me. From time to time, when we made small talk about

holidays or the weather, I could see what a lovely family the Savellis were—close-knit, tough, and intelligent. But whenever we returned to the subject of goats, the mood instantly hardened.

It turns out that the goat Guy stared at had not been debleated or shot in the leg. Guy had said he wanted a normal, healthy goat, so that’s what they gave him. It was herded into a small room that was empty but for a soldier with a video camera. Guy knelt on the floor in another room.

And he began to get that feeling inside him.

“I pictured a golden road going up into the sky,” he said. “And the Lord was there, and I walked into His arms, and I got a chill, and I

knew

it was right. I wanted to find a way to knock that goat down. We have this picture of St. Michael the Archangel with a sword. So I thought about that. I thought about St. Michael with this sword going …”

Guy mimed the action of St. Michael violently thrusting his sword downward into a goat.

“...Through the goat and …”

Guy smacked his hands together.

“ … Knocking it down to the ground. Inside of me I couldn’t even breathe. I was going …”