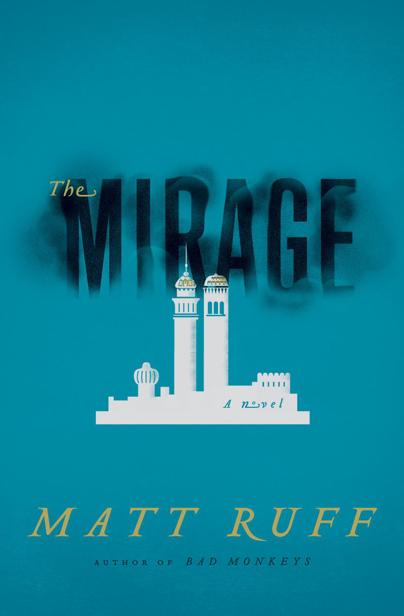

The Mirage: A Novel (51 page)

Read The Mirage: A Novel Online

Authors: Matt Ruff

“OK,” Samir says. “Which way?”

Three Muslims adrift in the desert could do worse than follow the Qibla direction. Of course Mustafa has no idea which direction that is, but he remembers the direction he was kneeling in, so they strike out that way. At first they try to travel in a straight line, but after trekking up and down a few dune faces in the noonday sun, they decide to zigzag instead, following the troughs between dunes.

They’ve only gone two or three kilometers when they come upon the jeep. It is buried nose-down in the sand, its front hood and most of its windshield covered, its tailgate and right rear wheel sticking up at an angle. Like Mustafa’s boot, it is unmarked but looks military. Its green paint job has been scoured by the sand.

Under a green canvas tarp in the tail bed they find several plastic jugs full of water. Mustafa cracks one open and drinks. The water is very warm but tastes fine. He passes the jug around.

After they’ve all drunk their fill, they investigate the front of the jeep. Amal, the smallest of them, crawls in through the open passenger window. She finds the ignition and tries it, but there’s not even the click of a solenoid in response. She has better luck with the glove box: Inside is a small pistol, .25-caliber with a nine-round clip. The clip is fully loaded and the barrel is clean; the slide moves easily. Mustafa is mildly troubled by this discovery but Amal takes it as a good omen. “It never hurts to be prepared,” she says, slipping the gun into her abaya.

Samir takes another look in the tail bed and finds a leather pouch with tobacco and some rolling papers. “Are there matches, too?” Amal inquires, and Samir produces a lighter from his back pocket.

Mustafa would love a smoke, but there’s something else he needs to take care of first. He grabs one of the water jugs and goes to find a private spot around the nearest dune. He washes his face, his hands, and his feet. He still doesn’t know the Qibla direction, but there’s a workaround for that: He says the required prayers, not once, but four times, each time turning himself by ninety degrees.

He’s finishing up the last set when a light breeze comes over the dune, carrying the sound of Amal’s voice saying her own prayers. Careful not to disturb her, Mustafa makes his way back to the jeep.

Samir has torn a long strip from the tarp and fashioned a turban for himself. It looks comical but will protect his scalp. Mustafa rolls a cigarette and they pass it back and forth until Amal returns.

They should probably use what’s left of the tarp to make some shade and sit out the hottest part of the day, but they are all impatient now to get somewhere, to find out where

somewhere

is, and so without even discussing it they each take a water jug and start walking again.

They walk for several hours, zigzagging between the dunes, using the position of the sun to maintain a more or less steady course. In the middle of the afternoon they find another military vehicle, a canvas-top troop truck, lying on its side. Samir crawls in the back, looking for more goodies. This time there’s no water or tobacco, but when he digs in the sand that’s drifted up inside, he finds a big tin can filled with something heavy.

Mustafa studies the length of the shadow cast by the truck, does a mental calculation, and goes off to pray again. When he gets back, Samir and Amal have found a can opener. “Figs,” Amal says. They sit in the back of the truck and eat fruit, lick syrup from their fingers. Then they get sleepy.

Mustafa naps for about an hour. When he wakes up, Samir is snoring like a buzz saw and Amal is gone. He steps outside and finds her standing up on the truck cab, balanced precariously on the passenger door. She is shading her eyes. “I see a city,” she says. Mustafa looks where she is looking but his view is blocked by a dune, so he climbs up beside her.

Now he can see it: out on the horizon, wavering and indistinct, its distance impossible to guess. “I see towers,” Amal says. “Do you see towers?”

“I see something,” says Mustafa.

They wake up Samir. He sees it too. “I hope it’s real,” he says. “I hope the people who live there speak Arabic.”

“If they speak English,” says Mustafa, “I’ll translate.”

“And if they speak Farsi,” says Amal, “I’ll tell you what

not

to say.”

They set out. The dunes no longer seem so steep, so they begin to travel in a straight line again, and as they climb up and down, they play a game to pass the time. When they are on top of the dunes and the city is visible, they describe what they think they can see. When they are down in the troughs and the city is hidden, they talk about what they would like to see, what they hope they will find when they get there.

“I hope prohibition is over,” Samir says. “I’d like to get a cold beer.”

“I hope there are more women in Congress,” Amal says. “A woman president would be nice.”

“I hope there is a Congress,” says Mustafa. “A republic—a

real

republic—of some kind.”

Hope. They are careful to use that word, and not

wish.

And they are careful not to speak of friends or family. But in the silences, as they labor up or downhill, that is what they think about: who will be waiting for them.

Amal thinks of her father. She pictures him on the steps of the city hall, in uniform, shoulder to shoulder with all the others who gave their lives for justice: These are the ones. She hopes to stand beside him again, but if that’s too much to ask, she is prepared to stand for him, and carry on his legacy.

Samir thinks of his sons. In his heart he is certain that they are out there somewhere. What he is less sure of is whether he will be permitted to see them. The majority of his thoughts are focused on this, and on how he will begin to search. But beyond Malik and Jibril, there is room in his hopes for one other—not so much a specific person, a specific man, as an idea of one. It is still not an idea he would dare to voice aloud, but he can at least conceive of it now, and wonder whether, on this side of the storm, some things might be possible that were not before.

Mustafa thinks, of course, of Fadwa. He doesn’t know if he will see her again. He doesn’t know, if he does, whether anything will be different. He would like a chance to tell her he is sorry, and he would certainly be willing to try again: To be kind. To be honest. To be a bit less of a fool. Trying doesn’t mean succeeding, though, and he is still the same man, with the same flaws.

But he is willing to try. And to ask for help. And that more than anything is what he hopes for: that waiting in the city will be one whom he can ask for help with his struggle—the struggle of the future he must still face, and the struggle of the past he must learn to let go.

They walk all the rest of that day, a day that seems to go on endlessly. But it does end, finally. As the sun sinks below the horizon, they crest one last dune, and there it is, sprawled on the plain below them: a white-walled city, with lights of evening just coming on.

They stand on the dune looking down.

“I don’t recognize it,” Amal says. “Do you?”

“No,” Samir says.

“No,” says Mustafa.

But it’s not entirely foreign to them. Here and there, along the unfamiliar streets, they see shapes they do recognize: domes and steeples and towers. And even now, in a minaret near the outer wall, a muezzin begins his cry, words and a language they know.

They stand on the dune and listen to the call. More lights come on. People move in the streets. “God willing,” says Mustafa. And then he and Samir and Amal go down, in hope, to the city.

Thanks are due, as always, to my one and only wife, Lisa Gold, who served as my first reader, sounding board, research assistant, and cheerleader. My agent, Melanie Jackson, offered encouragement at a time when I still wasn’t sure the novel would work. My publisher, Jonathan Burnham, and my editor, Rakesh Satyal, were also early supporters, and Rakesh helped me across the finish line with a minimum of pain and suffering. Tim Duggan shepherded me through publication. Others who gave assistance or encouragement include Alison Callahan, Nancy Gold, Rita and Harold Gold, Ernest Lehenbauer, Matthew Snyder, Neal Stephenson, Lydia Weaver, and Henry Wessells. Special thanks to the late (and sorely missed) Reverend Jack Ruff, whose insights into human nature continue to serve me well.

In constructing the mirage world, I drew upon many sources, including works by Peter Bergen, Mark Bowden, Anne Garrels, Shahla Haeri, William R. Polk, Thomas E. Ricks, Zainab Salbi, David Thibodeau, Evan Wright, Lawrence Wright, and Amira El-Zein. Quotations from the Quran are taken from Abdullah Yusuf Ali’s English-language translation. Bible quotations are taken from various translations, including the New International Version, the New Revised Standard, and the King James.

Finally, I am indebted to Karen Glass and Caitlin Foito, who started me on my way by asking me to tell them a story. It’s taken four and a half years, and the end result is surely not what they had in mind, but I am grateful they made the wish.

MATT RUFF

was born in New York City in 1965. He is the author of the award-winning novels

Bad Monkeys

and

Set This House in Order

, as well as the cult classics

Fool on the Hill

and

Sewer, Gas & Electric.

He is the recipient of a 2006 National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship. Ruff lives in Seattle with his wife, Lisa Gold.

Visit Matt Ruff on the web at www.bymattruff.com.

Visit

www.AuthorTracker.com

for exclusive information on your favorite HarperCollins authors.

Bad Monkeys

Fool on the Hill

Set This House in Order: A Romance of Souls

Sewer, Gas & Electric: The Public Works Trilogy

Jacket Design by Oliver Munday

THE MIRAGE.

Copyright © 2012 by Matt Ruff. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

FIRST EDITION

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ruff, Matt.

The mirage / Matt Ruff.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-06-197622-3

I. Title.

PS3568.U3615M57 2011

813'.54—dc22

2011012895

12 13 14 15 16

OV/RRD

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Epub Edition © JANUARY 2012 ISBN: 9780062097934

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd.

25 Ryde Road (P.O. Box 321)

Pymble, NSW 2073, Australia

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

2 Bloor Street East - 20th Floor

Toronto, ON, M4W, 1A8, Canada

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers (New Zealand) Limited

P.O. Box 1

Auckland, New Zealand

http://www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

77-85 Fulham Palace Road

London, W6 8JB, UK

http://www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

10 East 53rd Street

New York, NY 10022