The Mobile MBA: 112 Skills to Take You Further, Faster (Richard Stout's Library) (13 page)

Read The Mobile MBA: 112 Skills to Take You Further, Faster (Richard Stout's Library) Online

Authors: Jo Owen

As you dig deeper, you find most large organizations have radically different cultures in different groups: sales are different from R&D who are different from accounts. In banks, retail banking and investment banking live on different planets.

So what can you do about such cultural chaos and confusion? You can do two things:

•

Remember the words of Warren Buffett:

“I find that when a manager with a great reputation joins a firm with a lousy reputation, it is the reputation of the firm which remains intact.” So find a firm which suits your style: if you are entrepreneurial, do not join a risk averse firm even if they are pleading with you to sprinkle your entrepreneurial pixie dust over them. It will be the marriage from hell, and you will not survive. You have to find the context in which you can thrive. Above all, that means you have to be happy signing up to the culture of the firm you will join.

•

Set the culture for your own team.

You will be remembered less for what you do and more for how you are. If you want to be remembered as the duplicitous and authoritarian politician from marketing, so be it. Your team will take their cues from you. Every time you walk into the office with your little cloud of gloom, it will soon spread like a major depression across the office. If you are Machiavellian and mean, do not expect your team to be open, trusting, and generous. How you behave determines how your team behaves. Your choice.

A good way to fail as a CEO is to start a culture change program: it is unlikely to succeed, and even if it does it will take too long and may (or may not) affect the results of your business.

Cultural change initiatives are set up to fail from before they start. Here is why:

• Cultural revolutions have a bad name: think Mao and 50 million dead. Or Pol Pot and the killing fields.

• An attack on the culture of a firm is, by definition, an attack on the majority of the staff and the way they work. Most people resent being told that the way they have worked for 20 years is rubbish.

• Cultural change means mindset change: my bosses can mess with my roles and responsibilities, but they will not mess with my mind, thank you very much.

And yet a dysfunctional culture leads to dysfunctional results, so can you walk by on the other side of the road and pretend there is no problem?

If you want to change the culture, do not attack it head on. You will lose. Attack it crab wise: from the side. As a leader, this is what you can do to change the culture of your firm without ever stating that intention:

Changing culture

•

Be a role model for the values you believe in

, and be consistent in how you act.

•

Recognize and celebrate people who do things in the new way:

support other positive role models. You do not need to say the old ways are bad, you simply let the new ways grow in their place.

•

Find some moments of truth to make your point:

where there is a tough decision, be guided by the values you believe in and make sure everyone knows that is why you took the decision you made. People believe what you do, not what you say.

•

Hire and fire according to the new values.

A few ritual executions of the old guard will concentrate everyone’s minds wonderfully. Remember the old saying: to scare the monkey, kill a chicken. Make values an explicit part of the hiring criteria.

•

Change the compensation structure.

Pay drives behavior. If everyone is on an individual bonus, do not expect great teamwork. If you incentivize call center staff on the number of calls they handle, not on how well they handle the calls, do not expect great customer service. You get what you pay for.

•

Over-communicate.

Official communications such as the company newsletter have all the credibility of Pravda in the Soviet era. Few people read it and even fewer believe it. Hold town hall meetings, meet face to face, and explain what you are doing from a business perspective, not just a cultural perspective.

•

Be patient.

It will take time for everyone to work out the new rules of survival and success and to adapt. There will be game playing: people will change their face but not their minds. Be relentless and consistent in all that you do, so that eventually the new way of working becomes habit.

Occasionally, an employee will commit spectacular career hara-kiri and they make the firing decision very simple. Like when I found our bookkeeper was not just trying to defraud us, but was also an armed robber in his spare time. Easy decision.

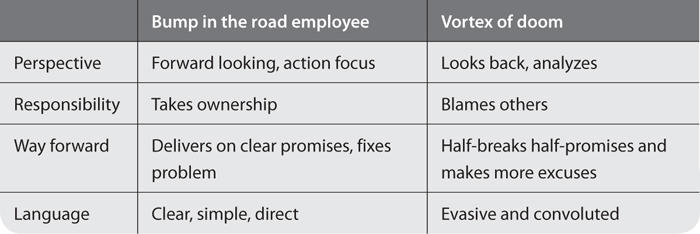

Mostly, the decision is tough because things are not so clear cut. The trick is to know if someone has hit a bump in the road or is in a vortex of doom. If they have hit a bump in the road, they will often come out of it stronger and wiser (at your expense) and will be a more valuable employee. Once they hit the vortex of doom, it is like a black hole: there is no known means of escape, although the slide to oblivion can be slow and ugly.

The difference is normally clear when you look at how they react to a setback.

When someone is in the doom vortex, move fast. The longer you leave it, the more they will drag others down with them.

When performance heads south it is rarely because of a lack of technical skills: an accountant does not suddenly become incompetent overnight. Poor performance is normally the result of poor people skills and poor values, which make it difficult for the employee to get things done. This is important because most people are hired for their technical skills, but fired for their people skills and values. So if you want to avoid firing people, hire the right people: look at their people skills and values as much as you look at their technical skills.

if you want to avoid firing people, hire the right people

Finally, be careful that you are not part of the problem. If there is a performance problem, then as the manager you are ultimately accountable for that. If there is a values problem, it may be that the two of you simply have different styles and cannot get along. So find some impartial advice before blundering in and earning yourself a lawsuit and damages.

Of course, you do not have to fire them. You may be able to move them on to some other department and let them make the painful decision.

In most business schools the ethics course need only teach two things:

•

Your ethics will be determined by your industry and your employer

.

•

Ethics is not about honesty and morality: it is much more important than that

.

Some employers have high ethical standards, others require a more flexible approach to ethics. The defense industry works to one set of standards, medical practice works to another. The CEO of a reinsurance brokerage firm assured me: “If you want to get ahead in this business, you have to put your liver on the line.” He was an alcoholic, and all his best brokers had very low golf handicaps. Understand the expectations and make your choice.

It would be nice to think we can keep separate standards from those of our employers. This is not the case: most of us rise or fall to the level of expectations and standards around us. The scandals which afflict the corporate world come largely because everyone bought into a way of doing things which seemed to make sense to the insiders, but then looked unacceptable when exposed to public scrutiny.

If you have high ethical standards, pick the right employer. If you are more flexible, there are plenty of firms which will be delighted to hire you.

Let’s make this simple: do you want to work for a boss you do not trust? Do you want to deal with a contractor you do not trust? Occasionally we may have to work with people we do not trust, but where possible most people prefer to work with other people they feel they can trust. So the point about morality and ethics is not to save the world: it is to show that you are someone that can be trusted. If you are not trusted, you will find it hard to attract a team, hard to get the support of colleagues, and hard to get clients. You will be functionally useless.

Building trust takes time and consistent behavior. The three drivers of trust are:

•

Values alignment:

do we have the same interests, values and priorities? You have to show you care not just for your own interests, but that you understand and care for the interests of your client and your team. When you do this well, you will hear managers spouting the jargon, “We are all singing from the same hymn sheet, you certainly talk the talk....”

•

Credibility.

You have to deliver on what you say. You even have to deliver on what you do not say. If you fail to disagree with someone when they are in full flow, then they will assume that you have agreed with what they are saying: you will by default have agreed to their project, their promotion request, their delivery deadline. Be very clear and very consistent in what you say and what you do not say.

•

Moments of truth.

There are always difficult moments: these are the moments when you build or destroy trust. Broken trust is like a broken vase: very difficult to put back together again perfectly. Moments of truth are those awkward moments when you have to deal with the underperformance of a colleague, or you have to disappoint a client. If you handle these moments promptly and positively, you can build trust. Shade the truth or deny the problem and you lose credibility.

Ethics, honesty, and morality are all fine things, but for all managers the most precious commodity is trust.

•

How to start a change effort

82

•

Setting up a project for success

84

•

Restructuring the organization

88

MBAs are useful, but it’s important to remember that an MBA is a classic university discipline. It is good at transferring a body of explicit knowledge from one generation to the next but is very poor at dealing with tacit knowledge. (Tacit knowledge is all about the know-how skills, as opposed to explicit knowledge which is all about know-what skills.) So most MBA courses struggle with operations, technology, and change: these are more know-how skills than know-what skills. But as a manager, you need to be comfortable with these skills: even if you are not an operations expert, you need to know what questions to ask and to know what good looks like. And all managers have to master the mysteries of change: if you cannot change things, then you are an administrator, not a manager. So this chapter takes you beyond the comfort zone of the MBA and into the wilds of practical management.

Administrators manage a status quo. Managers improve things, which means that they need to make change happen. To manage is to make change, but most people do not like change. Change implies risk, uncertainty, and doubt. And the risk is not impersonal business risk but a personal risk: will I be able to adapt to the new ways? So you start your change program with a cheery smile and quickly find yourself caught in the quicksand of corporate politics. All the objections to your idea will be stated very rationally, but in many cases the rational objections hide people’s personal fears. The more you deal with the rational objections, the less you deal with the real objections, which are personal. You find yourself going where most change programs go: nowhere.

most people do not like change

So before you start your change program, you need to know if it is set up to succeed or fail. Generals believe most battles are won and lost before the first shot is fired. The same is true of change efforts: failure or success is determined even before you start.

Over many years, one formula has accurately predicted whether change is going to succeed or fail. The formula is called the change equation. Here it is:

N × V × S × F > C

In plain English the equation states that change will succeed where a real Need for change (N) and a Vision of the change (V) with Support (S) combined with practical first steps (F) exceed the Costs and risks of the change (C).

Let’s look at what each term of the equation means in practice. The key is that the equation is not just about the likelihood of changing the organization: it is also about the likelihood of individuals in your team supporting your change.