The Monks of War (18 page)

Froissart, who obviously disliked Gloucester, had to admit that he was extremely popular. The irrepressible Duke ‘whose heart was by no means inclined to the French’ continued to wage a private war. When news reached England in 1396 of the slaughter of the largely French crusade at Nicopolis by the Turks, Gloucester was delighted, commenting that it served ‘those rare boasting Frenchmen’ right ; he added that were he King he would attack France at once now that she had lost so many of her best troops. Many Englishmen shared the Duke’s opinions. They had been fighting France for over half a century ; almost every summer ships filled with eager young soldiers had sailed from Sandwich to Calais or from Southampton to Bordeaux. War was still the nobility’s ideal profession ; the English aristocracy saw a command in France much as their successors regarded an embassy or a seat in the cabinet. Moreover, men of all classes from Gloucester to the humblest bondman, regarded service in France as a potential source of income : if the War had cost the English monarchy ruinous sums, it had made a great deal of money for the English people, for many of whom peace meant more than just unemployment. In modern terms, refusing to continue the War was as though a government were to decide to abolish football pools and horse-racing.

Richard II finally destroyed the leaders of the war party in 1397. The Duke of Gloucester gave the King his opportunity during a banquet at Westminster in June. Some of the garrison of Brest, which had just been sold to Brittany, were present and in his cups the Duke asked his nephew what they were going to live on, adding that they had never been properly paid. The King answered that they were living at his expense at four pleasant villages near London and would certainly receive their arrears. Gloucester exploded. ‘Sire, you ought first to hazard your life in capturing

The

routier

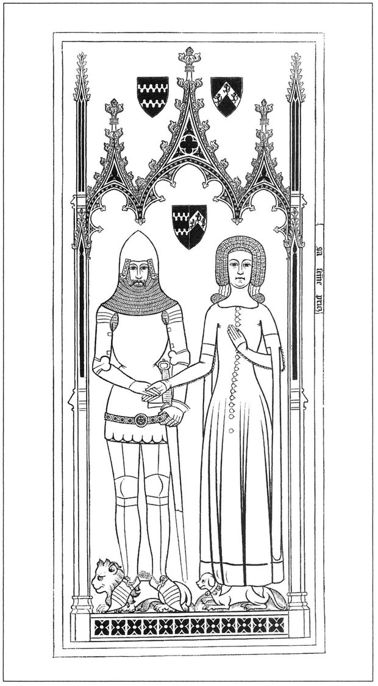

Sir Nicholas Dagworth. Captain of Flavigny in Burgundy in 1359, he led a ‘free company’ of mercenaries into Spain in 1367. Ironically, he negotiated a truce with the French for Richard II in 1388. From a brass of 1402 in the parish church at Blickling, Norfolk.

a city from your enemies before you think of giving up any city which your ancestors have conquered.’ Richard was furious and the Duke realized he had gone too far. In August Gloucester, Arundel and their friends met secretly at Arundel Castle in Sussex to discuss how to seize power and imprison the King. They were soon betrayed and arrested. Arundel was beheaded while Thomas of Gloucester, despite begging for mercy ‘as lowly and meekly as a man may’ was smothered in a feather-bed in his prison at Calais. (Though Froissart heard that he was strangled with a towel.)

Richard had now become almost insanely tyrannical, flouting the established laws and customs of the realm. ‘The King did what he would in England and none dared speak against him.’ A figure even more tragic than that portrayed by Shakespeare, not only did he lose a kingdom but he lost it from wanting to possess it more completely. He finally overreached himself by exiling Henry of Bolingbroke, Gaunt’s son and heir, and then when Gaunt died in 1398, making Bolingbroke’s banishment lifelong and confiscating all his estates. This and other blatant injustices, such as making anyone he disliked pay a crippling sum for a pardon, outraged the English magnates. In 1399 Bolingbroke returned to England while Richard was away in Ireland and found so much support that he was able to depose the King, who, a modern biographer suggests, became ‘a mumbling neurotic sinking rapidly into a state of complete melancholia’. Bolingbroke ascended the throne as Henry IV, the first of the Lancastrian dynasty. Richard died a few months later, probably of self starvation-‘some had on him pity and some none, but said he had long deserved death,’ observes Froissart. Whatever his faults Richard II had been genuine in his attempts to make peace with France, and his failure meant the revival of the War.

6

Burgundy and Armagnac: England’s Opportunity 1399-1413

The Duke of Burgundy ... was sore abashed and said ‘Out, harrow! What mischief is this? The King [of France] is not in his right mind, God help him. Fly away, nephew, fly away, for the King would slay you.’

Froissart

Normandy would still be French, the noble blood of France would not have been spilt nor the lords of the Kingdom taken away into exile, nor the battle lost, nor would so many good men have been killed on that frightful day at Agincourt where the King lost so many of his true and loyal friends, had it not been for the pride of this wretched name Armagnac.

The Bourgeois of Paris

Events across the Channel were also conspiring to prevent a lasting peace between France and England. The growing rivalry among the Valois Princes of the Blood was to end by plunging their country into a French Wars of the Roses, and in consequence France would be unable to defend herself against invasion. It was to provide England with her greatest opportunity.

In 1392 Charles VI had gone mad while riding through a forest, slaying four of his entourage and even trying to kill his nephew. Later he would run howling like a wolf down the corridors of the royal palaces ; one of his phobias was to think himself made of glass and suspect anyone who came near of trying to shatter him. He recovered, but not for long, lucid spells alternating with increasingly lengthy bouts of madness-‘far out of the way, no medicine could help him,’ explains Froissart. (The cause may have been the recently diagnosed disease of porphyria, which was later to be responsible for George III’s insanity.)

When the King was crazy France was ruled by Burgundy, who annually diverted one-eighth to one-sixth of the royal revenues to his own treasury. When Charles was sane his brother Louis, Duke of Orleans, held power, no less of a bloodsucker than his uncle Philip. Louis hoped to use French resources to forward his ambitions in Italy, where he had a claim to Milan through his wife Valentina, the daughter and heiress of Gian Galeazzo Visconti (and a lady ‘of high mind, envious and covetous of the delights and state of this world’). He imposed savage new taxes and was also suspected of practising magic, becoming even more disliked than Burgundy. Frenchmen began to divide into two factions. Few can have realized that this was the birth of a dreadful civil war which would last for thirty years and put France at the mercy of the English. However, fighting did not break out for almost another two decades.

The French were stunned by the news of King Richard’s deposition. Henry IV hastily sent commissioners to confirm the truce and Charles VI’s government agreed, although the new English King owed a good deal of his home support to his repudiation of Richard’s policy of peace. Having bought time, Henry refused to send little Queen Isabel home. She was only restored to her family at the end of July 1400, without her jewels or her dowry; he explained that he was keeping them because King John’s ransom had not been paid in full.

In fact Henry was desperately short of money. During Richard II’s reign the average annual revenue from customs duties on exported wool had been £46,000, but by 1403 it had fallen to £26,000 ; later it rose but only to an average of £36,000. Calais cost the exchequer £17,000 a year and Henry could not pay its garrison ; eventually the troops mutinied and had to be bought off with loans from various rich merchants. Moreover the King was plagued by revolts by great magnates and by a full-scale national rising in Wales. Henry IV was therefore in no position to go campaigning in France, though everyone knew that he hoped to do so one day.

Louis of Orleans believed that the time was now ripe to conquer Guyenne. In 1402 the title of Duke of Guyenne was bestowed on Charles VI’s baby son, a gross provocation as Henry IV had already given it to the Prince of Wales. In 1404, with the approval of the French Council, Louis of Orleans began a systematic campaign against the duchy and took several castles. Henry thought of going to the aid of the Guyennois in person, but was only able to send Lord Berkeley with a small force. In 1405 the situation worsened, the Constable Charles d‘Albret overrunning the north-eastern borders, the Count of Clermont attacking over the Dordogne, and the Count of Armagnac advancing from south of the Garonne to menace Bordeaux. In 1406 the Mayor, Sir Thomas Swynborne, prepared the ducal capital for a siege after the enemy had reached Fronsac, Libourne and Saint-Emilion, almost on the outskirts of Bordeaux (and to the grave detriment of the vineyards). The Archbishop of Bordeaux wrote desperately to Henry ‘we are in peril of being lost’, and in a later letter reproached the King for abandoning them. Somehow the Bordelais beat off the attack, defeating the French in a river battle on the Gironde in December 1406. The other Guyennois cities were also loyal to the Lancastrians ; even when occupied by the French Bergerac appealed to the English for protection. When in 1407 Orleans failed to take Blaye (the last stronghold on the Gironde before Bordeaux), he and his troops, already disheartened by disease and unending rain, withdrew in despair. Guyenne was left in peace to make a full recovery.

The French offensive had not been confined to Guyenne. Privateers roamed the Channel and the Count of Saint-Pol raided the Isle of Wight in 1404, demanding tribute in the name of Richard II’s Queen though with scant success. An attack on Dartmouth was also unsuccessful while an attempt to take Calais failed disastrously. In July 1404 Charles VI concluded an alliance with Owain Glyndwr whom he recognized as Prince of Wales ; but a French expedition of 1,000 men-at-arms and 500crossbowmen was prevented from sailing by bad weather. The force which eventually landed at Milford Haven the following year was too small to be of much use to the Welsh; in any case Owain’s rising was already doomed. In 1407 dramatic developments in France precluded any further interference in the affairs of Wales, let alone of England.

In 1400 the French monarchy had once again appeared to be the strongest power in western Europe. It was France who mounted the Crusade of Nicopolis in 1396 to aid the Hungarians against the Turkish onslaught and, though the crusaders met with a terrible defeat, even to mount such an operation was a remarkable achievement. Furthermore France still possessed her own Pope at Avignon. She had tamed Brittany and absorbed Flanders and dominated the Low Countries. She had also acquired the overlordship of Genoa and was now engaged on an ambitious Italian policy which might well gain her Milan.

This appearance of strength was the hollowest of façades, and owed more to the splendour of the French court and of the French Princes than to reality. For the realm was divided into great

apanages

as, unlike England, French duchies and counties were territorial entities, sometimes whole provinces, which went with the title and constituted semi-independent palatinates. (The only remotely comparable parallel in England was the Duchy of Lancaster.) The greedy Valois magnates who held them were usually content to live in semi-regal splendour in their beautiful châteaux, even if the countryside around them was still ravaged by

routiers.

There were two exceptions, the Dukes of Burgundy and Orleans.

Sir John de la Pole, nephew of Richard II’s Lord Chancellor and father-in-law to the Lollard heretic Sir John Oldcastle, with his wife Joan, daughter of Lord Cobham. From a brass of 1380 in the parish church at Chrishall, Essex.

Philip the Bold of Burgundy had died in April 1404, to be succeeded by his son John the Fearless-so called from gallant behaviour during the Crusade of Nicopolis. He was a taciturn little man, hard, energetic and charmless and, to judge from a famous contemporary portrait, singularly ugly, with an excessively long nose, an undershot jaw and a crooked mouth. In character, in Perroy’s view, he was even more ambitious than his father and ‘harsh, cynical, crafty, imperious, gloomy and a killjoy’. No one could have been more different from his refined and graceful, if scandalous cousin of Orleans.

Both Dukes were equally determined to rule France. They were opposed to each other in almost every important matter of policy. While John of Burgundy supported the Pope of Rome to please his Flemish subjects, Louis of Orleans upheld the Pope at Avignon ; John opposed war with England because of the danger to Flemish trade, but Louis was hot against the English. Council meetings were wrecked by the Dukes’ loud arguments and recriminations, while their followers-who constituted two political parties—brawled in the streets. When the Orleanists adopted the badge of a wooden club to signify Louis’s intention of beating down opposition, John made his Burgundians sport a carpenter’s plane to show that he would cut the cudgel down to size. However on 20 November 1407 Duke John and Duke Louis took Communion together, in token of reconciliation. Only three days later, on a pitch-black Wednesday night and after visiting the Queen, Louis of Orleans was ambushed as he went down the rue Vieille-du-Temple ; his hand was chopped off (to stop it raising the Devil) and his brains were scattered in the road. The Duke of Burgundy wept at his cousin’s funeral-‘never was a more treacherous murder,’ he groaned—but two days later, realizing that the assassins were about to be discovered, he blurted out to an uncle, ‘I did it ; the Devil tempted me.’ He fled from Paris and rode hard for Flanders.