The Moses Stone (23 page)

“You can’t be serious, Angela. Is there any credible evidence that Moses even existed?”

“We’ve been down this route before, Chris,” she said with a slight smile, “and I think you know my views. Like Jesus, there’s no physical evidence that Moses was a real person but, unlike Jesus, he does appear in more than one ancient source, so he’s got more credibility for that reason alone. He’s mentioned in the writings of numerous Greek and Roman historians, as well as in the Torah, and even in the Qur’an.

“But whether or not there’s any historical reality to Moses as a person rather misses the point. If that man Yacoub was right, the people who hid the relics and prepared the tablets two thousand years ago

did

believe they possessed something that had belonged to Moses. That means whatever the relic actually was, it was already ancient even then. And any kind of stone tablet dating from well over two millennia ago would be an extremely important archaeological find.”

did

believe they possessed something that had belonged to Moses. That means whatever the relic actually was, it was already ancient even then. And any kind of stone tablet dating from well over two millennia ago would be an extremely important archaeological find.”

“So you’re going to start looking for it?”

“Yes, I am. I simply can’t pass up a chance like this. It’s the opportunity of a lifetime.”

Bronson looked at her face. No longer pale, it was flushed with excitement and her beautiful hazel eyes sparkled with anticipation. “Despite all you’ve gone through today? You nearly got killed in that cellar.”

“You don’t have to remind me. But Yacoub is dead, and whatever his gang gets up to now, I doubt if chasing us to try to recover that clay tablet is going to be high on their list of priorities. In any case, we’ll be leaving the country within a couple of hours, and I don’t think that either the Silver Scroll or the Mosaic Covenant is in Morocco. The reference to Qumran is clear enough, and I have a feeling that—whatever was hidden by the people who wrote these tablets—they were buried in Judea or somewhere in that general area. The clay tablet the O’Connors found must tell us their whereabouts.”

Bronson nodded. “Well, if you want to do any more investigating, I’m afraid you’ll have to do it by yourself. I’ve got to get back to Maidstone to write up my report, and I might even get sucked into the investigation into Kirsty Philips’s murder. I certainly don’t think I’ll be able to convince Dickie Byrd that I suddenly need to head off to Israel. Are you sure that this is worth following up?”

Angela looked at him. “Definitely,” she said. She opened her handbag, extracted a few folded sheets of paper and began looking at them.

“Is that the Aramaic text?” Bronson asked.

Angela nodded. “Yes. I still can’t work out how the coding system could have worked. I was so sure there were four tablets in the set, but the position of those two Aramaic words

Ir-Tzadok

and

B’Succaca

screws up that idea.”

Ir-Tzadok

and

B’Succaca

screws up that idea.”

Bronson glanced down at the sheets of paper, then looked back at the road ahead.

“Tell me again how you think they’d have prepared the tablets,” he suggested.

“We’ve been through this, Chris.”

“Humor me,” Bronson said. “Tell me again.”

Patiently, Angela explained her theory that the small diagonal line she’d observed on the pictures of each of the tablets meant there had originally been a single slab of clay that had then been cut into four quarters, and that each diagonal line was one part of a cross, cut into the clay at the center of the slab to indicate the original positions of those quarters.

“So you’ve got four tablets, each covered in Aramaic script that’s always read from right to left, but on the bottom two the only way that

Ir-Tzadok

and

B’Succaca

appear in the right order is if you read the two words backward, from left to right?”

Ir-Tzadok

and

B’Succaca

appear in the right order is if you read the two words backward, from left to right?”

“Exactly,” Angela replied, “which is why I must have got it wrong. The only thing that makes sense is that the tablets must be read in a line from right to left. But if that

is

the case, then what’s the purpose of the diagonal lines?”

is

the case, then what’s the purpose of the diagonal lines?”

Bronson was silent for a couple of minutes, staring at the ribbon of tarmac unrolling in front of the car, while his brain considered and then rejected possibilities. Then he smiled slightly, and then laughed aloud.

“What?” Angela asked, looking irritated.

“It’s obvious, blindingly obvious,” he said. “There’s one simple way that you could position the tablets in a square, as you’ve suggested, and still read those two words in the right order. In fact,” Bronson added, “it’s so obvious I’m really surprised you didn’t see it yourself.”

Angela stared at the paper and shook her head. Then she looked across at Bronson.

“OK, genius,” she said, “tell me.”

42

Angela spread out her notes on the table in front of her and bent forward, studying what she’d written. They were in the departure lounge of the Mohammed V airport waiting for their flight to London to be called.

“I think your solution to the puzzle of the clay tablets has to be right. I wrote out everything we’d deciphered, but in the order you suggested, and now it does seem to make more sense. I just wish we had better pictures of the Cairo museum and the O’Connor tablets—it would be a great help if we could read a few more words of the inscriptions on those two.”

She looked down again at the papers in front of her. Bronson’s idea was

so

simple that she, too, was amazed it hadn’t occurred to her.

so

simple that she, too, was amazed it hadn’t occurred to her.

Aramaic, he’d said, was written from right to left, and they’d more or less agreed that there had originally been four tablets, arranged in a square. Why not, Bronson had proposed, read the text starting with the first word at the right-hand end of the top line of the top right tablet—which they didn’t have, of course—and then read the word in the same position on the tablet at the top left of the square. Then move to the bottom left, then bottom right and back to the top right, and so on, in a kind of counterclockwise circle. That, at least, meant that the words

Ir’Tzadok

and

B’Succaca

could be read in the correct sequence.

Ir’Tzadok

and

B’Succaca

could be read in the correct sequence.

But even that didn’t produce anything that seemed totally coherent—it just formed very short and disjointed phrases—until they tried reading one word from each line and next the word from the line directly

below

it, instead of the next word on the

same

line. Then, and only then, did a kind of sense begin to emerge.

below

it, instead of the next word on the

same

line. Then, and only then, did a kind of sense begin to emerge.

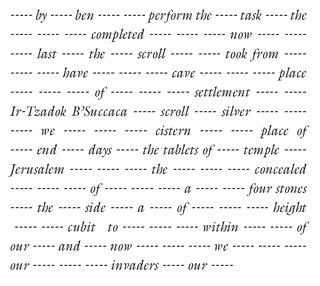

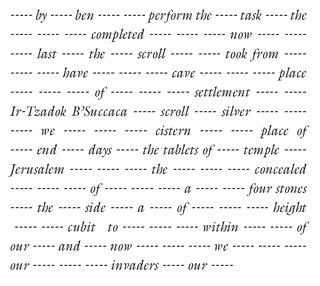

What they now had read:

“Have you tried filling in any of the blanks?” Bronson asked.

“Yes.” Angela nodded. “It’s not as easy as you might think, because you can easily end up tailoring the text to whatever it is you want it to say. I’ve tried, and a few of the missing words seem to be fairly obvious, like the end of the last line. The word ‘invaders’ seems to stand out as being different to the rest of the inscription, so I think that’s possibly a part of a political statement, something like ‘our fight against the invaders of our land.’ That would be a justification of their opposition to, most probably, the Romans, who were all over Judea during the first century AD.

“The rest of it is more difficult, but there are a couple of things we can be certain about. These tablets

do

refer to Qumram: the words

Ir-Tzadok B’Succaca

make that quite definite. And in the same sentence, or possibly at the beginning of the next one, I’m fairly sure that those three words mean the ‘scroll of silver,’ the Silver Scroll. That’s what really excites me. The problem is that, if the author of this text did possess the scroll and then hid it somewhere, presumably in a cistern, which is what I’m hoping, we still don’t know exactly where to start looking, apart from Qumran, obviously. And the country, of course, was full of wells and cisterns at this period. Every settlement, from a single house right up to large villages and towns, had to have a source of water close by. I’ve no idea how many cisterns there were in first-century Judea, but I guess the numbers would run into the thousand, maybe even tens of thousands.”

do

refer to Qumram: the words

Ir-Tzadok B’Succaca

make that quite definite. And in the same sentence, or possibly at the beginning of the next one, I’m fairly sure that those three words mean the ‘scroll of silver,’ the Silver Scroll. That’s what really excites me. The problem is that, if the author of this text did possess the scroll and then hid it somewhere, presumably in a cistern, which is what I’m hoping, we still don’t know exactly where to start looking, apart from Qumran, obviously. And the country, of course, was full of wells and cisterns at this period. Every settlement, from a single house right up to large villages and towns, had to have a source of water close by. I’ve no idea how many cisterns there were in first-century Judea, but I guess the numbers would run into the thousand, maybe even tens of thousands.”

She looked down at the deciphered text, studying the few words they’d managed to translate. If only they could fill one or two more of the blanks, they’d have some idea where to begin their search.

Bronson’s next question echoed her thoughts. “Assuming the museum will agree to let you go out to Israel, where do you think you should start looking?”

Angela sighed and rubbed her eyes. “I’ve no idea. But the reference we’ve managed to decode is the first tangible clue to a relic whose existence has been suspected for over fifty years. Half the archaeologists in the field that I’ve talked to have spent some time searching for the Silver Scroll, and the other half have dismissed it out of hand as a myth. But the O’Connors’ clay tablet is almost certainly contemporary with the relic, and I think the reference is a strong enough piece of evidence to follow up. And there’s something else.”

“What?”

“I don’t know that much about Israel and Jewish history, so I’m going to need some specialist help, from somebody who speaks Hebrew, somebody who knows the country and its history.”

“You’ve got someone in mind?”

Angela nodded and smiled. “Oh, yes. I know exactly who to talk to. And he’s actually based in Israel—in Jerusalem, in fact—so he’s right on the spot.”

43

Bronson felt drained. He seemed to have spent all the previous day sitting in an aircraft, and the damp, gray skies were an unpleasant reminder that he was back in Britain, in stark contrast to the few hot and sunny days he’d just spent down in Morocco. He punched the address Byrd had sent him by text into the unmarked car’s satnav and headed toward Canterbury.

When he arrived at the house, there were two police vans parked in the driveway and a couple of cars on the road outside the property. The front door was standing slightly ajar, and he slipped under the “crime scene” tape and stepped into the hall.

“You’re Chris Bronson, right?” A beefy, red-faced man wearing a somewhat grubby gray suit greeted him.

Bronson nodded and showed his warrant card.

“Right, I’m Dave Robbins. Come through into the dining room to keep out of the way of the SOCOs—they’re just finishing up in the lounge, and then we’re out of here. Now,” he said, when they were both seated at the dining table, “I gather from Dickie Byrd that you’ve had some contact with the victim?”

“I met her and her husband a couple of times in Morocco,” Bronson agreed, and explained what had happened to Kirsty Philips’s parents.

“Do you think there’s any connection between their deaths and her murder?” Robbins asked.

Bronson paused for a few moments before he replied. He was absolutely certain that the three deaths were connected, and that the missing clay tablet was at the heart of the matter, but he didn’t see how explaining all that would help Robbins find Kirsty’s killer.

“I don’t know,” he said finally. “It’s a hell of a coincidence if they’re unconnected, but I can’t think what the connection could be. What actually happened here? How did she die?”

In a few short sentences, Robbins explained what the police had found when they arrived at the house.

As he listened, Bronson’s mind span back to the hotel in Rabat, and to the way Kirsty had looked when he’d seen her there: bright and full of life, her natural vivacity subdued only because of the double tragedy that had decimated her family. Intellectually he accepted the truth of what Robbins had told him, but on an emotional level it was still difficult to believe what had happened.

“Who raised the alarm?” he asked.

“One of the neighbors thought she’d pop in and offer her condolences for the loss of her parents. She went to the side door, saw Kirsty lying dead on the floor, and ran screaming up the road to her own house to dial triple nine. We’ve already done a door-to-door but we haven’t found anyone who saw Kirsty arriving, and only two people noticed the neighbor doing a four-minute mile and howling like a banshee.”

“Right,” Bronson said. “I can’t think what connection this has to Morocco. My guess is she might have disturbed a burglar, one of those sick bastards who find out who’s died and then target their houses. And because she was only hit once, he might not have intended to kill her. If he thought the house was empty and she suddenly stepped out in front of him, he might have just swung his jimmy as a kind of reflex action, and hit her harder than he meant to. In my opinion, I think it’s most likely that you’re looking at a totally unrelated crime.”

Other books

Taken (Warriors of Karal Book 3) by Harmony Raines

More Than a Mistress by Leanne Banks

How the Dead Dream by Lydia Millet

On the Corner of Heartache and Hopeful--MIC by Bailey, Lynda

His to Possess by Opal Carew

ZAK SEAL Team Seven Book 3 by Silver, Jordan

Tempted by a Dangerous Man by Cleo Peitsche

Acquiring Trouble by Kathleen Brooks

The Divergent Series Complete Collection by Veronica Roth

Project Sweet Life by Brent Hartinger