The Mother: A Novel (27 page)

Read The Mother: A Novel Online

Authors: Pearl S. Buck

Then a guard ran out and picked the mother up and threw her to one side upon the road and there she lay in the dust. Then the crowd marched on and out of sight and to that southern gate, and suddenly a wild song burst from them and they went singing to their death.

At last the two men came and would have lifted up the mother, but she would not let them. She lay there in the dust a while, moaning and listening in a daze to that strange song, yet knowing nothing, only moaning on.

And yet she could not moan long either, for a guard came from the gaol gate and prodded her most rudely with his gun and roared at her, “Off with you, old hag—” and the two men grew afraid and forced the mother to her feet and set her on the ass again and turned homeward slowly. But before they reached the southern gate they paused a while beside a wall and waited.

They waited until they heard a great roar go up, and then the two men looked at each other and at the old mother. But if she heard it or knew what it was, she made no sign. She sat drooping on the beast, and staring into the dust beneath its feet.

Then they went on, having heard the cry, and they met the crowd scattering and shouting this and that. The men said nothing nor did the old mother seem to hear, but some cried out, “A very merry death they died, too, and full of courage! Did you see that young bold maid and how she was singing to the end and when her head rolled off I swear she sang on a second, did she not?”

And some said, “Saw you that lad whose red blood spurted out so far it poured upon the headsman’s foot and made him curse?”

And some were laughing and their faces red and some were pale, and as the two men and the mother passed into the city gate, there was a young man there whose face was white as clay and he turned aside and leaned against the wall and vomited.

But if she saw or heard these things the mother said no word. No, she knew the lad was dead now; dead, and no use silver or anything; no use reproach, even if she could reprove. She longed but for one place and it was to get to her home and search out that old grave and weep there. It came across her heart most bitterly that not even had she any grave of her own dead to weep upon as other women had, and she must go and weep on some old unknown grave to ease her heart. But even this pang passed and she only longed to weep and ease herself.

When she was before their door again she came down from the ass and she said pleading to her elder son, “Take me out behind the hamlet—I must weep a while.”

The cousin’s wife was there and heard it and she said kindly, shaking her old head and wiping her eyes on her sleeves, “Aye, let the poor soul weep a while—it is the kindest thing—”

And so in silence the son led his mother to the grave and made a smooth place in the grass for her to sit upon and pulled some other grass and made it soft for her. She sat down then and leaned her head upon the grave and looked at him haggardly and said, “Go away and leave me for a while and let me weep.” And when he hesitated she said again most passionately, “Leave me, for if I do not weep then I must die!”

So he went away saying, “I will come soon to fetch you, mother,” for he was loath to leave her there alone.

Then did the mother sit and watch the idle day grow bright. She watched the sun come fresh and golden over all the land as though no one had died that day. The fields were ripe with late harvest and the grain was full and yellow in the leaf and the yellow sun poured over all the fields. And all the time the mother sat and waited for her sorrow to rise to tears in her and ease her broken heart. She thought of all her life and all her dead and how little there had been of any good to lay hold on in her years, and so her sorrow rose. She let it rise, not angry any more, nor struggling, but letting sorrow come now as it would and she took her measure full of it. She let herself be crushed to the very earth and felt her sorrow fill her, accepting it. And turning her face to the sky she cried in agony, “Is this atonement now? Am I not punished well?”

And then her tears came gushing and she laid her old head upon the grave and bent her face into the weeds and so she wept.

On and on she wept through that bright morning. She remembered every little sorrow and every great one and how her man had quarreled and gone and how there was no little maid to come and call her home from weeping now and how her lad looked tied to that wild maid and so she wept for all her life that day.

But even as she wept her son came running. Yes, he came running over the sun-strewn land and as he ran he beckoned with his arm and shouted something to her but she could not hear it quickly out of all her maze of sorrow. She lifted up her face to hear and then she heard him say, “Mother—mother—” and then she heard him cry, “My son is come—your grandson, mother!”

Yes, she heard that cry of his as clear as any call she ever heard her whole life long. Her tears ceased without her knowing it. She rose and staggered and then went to meet him, crying, “When—when—”

“But now,” he shouted laughing. “This very moment born—a son—I never saw a bigger babe and roaring like a lad born a year or two, I swear!”

She laid her hand upon his arm and began to laugh a little, half weeping, too. And leaning on him she hurried her old feet and forgot herself.

Thus the two went to the house and into that room where the new mother lay upon her bed. The room was full of women from the hamlet who had come to hear the news and even that old gossip, the oldest woman of them all now, and very deaf and bent nigh double with her years, she must come too and when she saw the old mother she cackled out, “A lucky woman you are, goodwife—I thought the end of your luck was come, but here it is born again, son’s son, I swear, and here be I with nothing but my old carcass for my pains—”

But the old mother said not one word and she saw no one. She went into the room and to the bed and looked down. There the child lay, a boy, and roaring as his father said he did, his mouth wide open, as fair and stout a babe as any she had ever seen. She bent and seized him in her arms and held him and felt him hot and strong against her with new life.

She looked at him from head to foot and laughed and looked again, and at last she searched about the room for the cousin’s wife and there the woman was, a little grandchild or two clinging to her, who had come to see the sight. Then when she found the face she sought the old mother held the child for the other one to see and forgetting all the roomful she cried aloud, laughing as she cried, her eyes all swelled with her past weeping, “See, cousin! I doubt I was so full of sin as once I thought I was, cousin—you see my grandson!”

Pearl S. Buck (1892–1973) was a bestselling and Nobel Prize-winning author of fiction and nonfiction, celebrated by critics and readers alike for her groundbreaking depictions of rural life in China. Her renowned novel

The Good Earth

(1931) received the Pulitzer Prize and the William Dean Howells Medal. For her body of work, Buck was awarded the 1938 Nobel Prize in Literature—the first American woman to have won this honor.

Born in 1892 in Hillsboro, West Virginia, Buck spent much of the first forty years of her life in China. The daughter of Presbyterian missionaries based in Zhenjiang, she grew up speaking both English and the local Chinese dialect, and was sometimes referred to by her Chinese name, Sai Zhenzhju. Though she moved to the United States to attend Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, she returned to China afterwards to care for her ill mother. In 1917 she married her first husband, John Lossing Buck. The couple moved to a small town in Anhui Province, later relocating to Nanking, where they lived for thirteen years.

Buck began writing in the 1920s, and published her first novel,

East Wind: West Wind

in 1930. The next year she published her second book,

The Good Earth

, a multimillion-copy bestseller later made into a feature film. The book was the first of the Good Earth trilogy, followed by

Sons

(1933) and

A House Divided

(1935). These landmark works have been credited with arousing Western sympathies for China—and antagonism toward Japan—on the eve of World War II.

Buck published several other novels in the following years, including many that dealt with the Chinese Cultural Revolution and other aspects of the rapidly changing country. As an American who had been raised in China, and who had been affected by both the Boxer Rebellion and the 1927 Nanking Incident, she was welcomed as a sympathetic and knowledgeable voice of a culture that was much misunderstood in the West at the time. Her works did not treat China alone, however; she also set her stories in Korea (

Living Reed

), Burma (

The Promise

), and Japan (

The Big Wave

). Buck’s fiction explored the many differences between East and West, tradition and modernity, and frequently centered on the hardships of impoverished people during times of social upheaval.

In 1934 Buck left China for the United States in order to escape political instability and also to be near her daughter, Carol, who had been institutionalized in New Jersey with a rare and severe type of mental retardation. Buck divorced in 1935, and then married her publisher at the John Day Company, Richard Walsh. Their relationship is thought to have helped foster Buck’s volume of work, which was prodigious by any standard.

Buck also supported various humanitarian causes throughout her life. These included women’s and civil rights, as well as the treatment of the disabled. In 1950, she published a memoir,

The Child Who Never Grew

, about her life with Carol; this candid account helped break the social taboo on discussing learning disabilities. In response to the practices that rendered mixed-raced children unadoptable—in particular, orphans who had already been victimized by war—she founded Welcome House in 1949, the first international, interracial adoption agency in the United States. Pearl S. Buck International, the overseeing nonprofit organization, addresses children’s issues in Asia.

Buck died of lung cancer in Vermont in 1973. Though

The Good Earth

was a massive success in America, the Chinese government objected to Buck’s stark portrayal of the country’s rural poverty and, in 1972, banned Buck from returning to the country. Despite this, she is still greatly considered to have been “a friend of the Chinese people,” in the words of China’s first premier, Zhou Enlai. Her former house in Zhenjiang is now a museum in honor of her legacy.

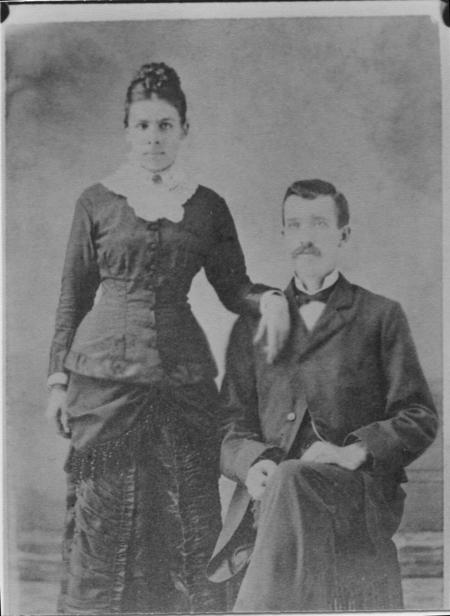

Buck’s parents, Caroline Stulting and Absalom Sydenstricker, were Southern Presbyterian missionaries.

Buck was born Pearl Comfort Sydenstricker in Hillsboro, West Virginia, on June 26, 1892. This was the family’s home when she was born, though her parents returned to China with the infant Pearl three months after her birth.

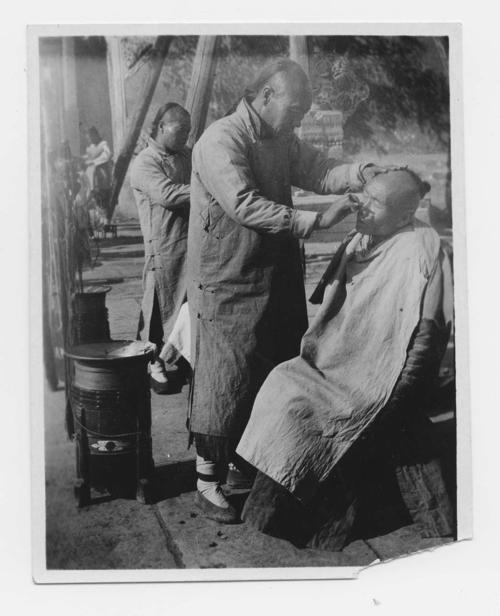

Buck lived in Zhenjiang, China, until 1911. This photograph was found in her archives with the following caption typed on the reverse: “One of the favorite locations for the street barber of China is a temple court or the open space just outside the gate. Here the swinging shop strung on a shoulder pole may be set up, and business briskly carried on. A shave costs five cents, and if you wish to have your queue combed and braided you will be out at least a dime. The implements, needless to say, are primitive. No safety razor has yet become popular in China. Old horseshoes and scrap iron form one of China’s significant importations, and these are melted up and made over into scissors and razors, and similar articles. Neither is sanitation a feature of a shave in China. But then, cleanliness is not a feature of anything in the ex-Celestial Empire.”