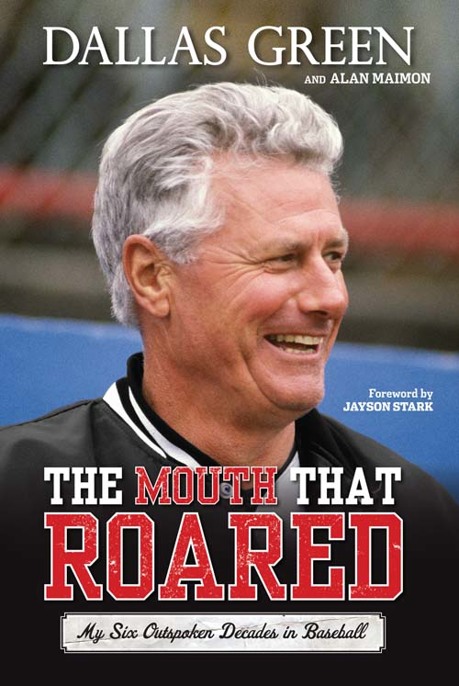

The Mouth That Roared

Read The Mouth That Roared Online

Authors: Dallas Green

~

For my family and my baseball family

Contents

Foreword by Jayson Stark

I can still hear his thundering voice, all these years later. The sonic booms still explode inside my head. The words still come roaring at me, as loudly, as emphatically, as unforgettably as they did on the night that Dallas Green and I came to be linked in Philadelphia baseball lore forever.

Linked by three words I’ll never live down—and neither will he:

“(Bleep) you, Jayson.”

The date was August 12, 1981. I was a young Phillies beat writer for the

Philadelphia Inquirer

. Dallas was already a living legend, the only man in the history of his franchise to manage the Phillies to a World Series championship. I’d been covering him for one year, 11 months, and 12 days. Not one of those days was what you’d call boring. Not one. And that was all the manager’s doing. All of it.

I’d come to learn, in those 23½ months, that you never knew what Dallas might say or do—especially say—on any given night at the ballpark. He was the smartest man in the room. He was also the loudest voice in the room. Any room. He was larger than life. He was louder than life. And when he had a message to deliver—which was pretty much every minute of every day—he had a way of getting his point across.

And when those messages came spilling out of him, you didn’t just need a pen, a pad, and a tape recorder to take them all in. You needed a Richter scale.

But in all the time I’d covered Dallas Green, I don’t ever remember finding him in such a constantly agitated state as I did in the first couple of weeks of August 1981. The baseball strike had just ended. The season was getting ready to rev up again. And no one was more aggravated than the manager of the defending champs that baseball had decided to split its season in two: if you were in first place when the strike hit in June, as the Phillies were, you had already clinched your playoff spot. So, there were Dallas and his team, with two months and 52 games to play, but, essentially, nothing to play for.

Let’s just say his unhappiness, over what he so affectionately called that “split (bleeping) season,” came up once or twice. Or 12 times. Or 50. You could feel something building inside him. And it wasn’t good. But then, on that fateful night of August 12, Mount Dallas-uvius erupted.

The season had resumed two days earlier. The manager was hopeful his pitchers would keep his team focused and competitive while the position players eased back into playing shape. But three games later, his pitching staff had coughed up 23 runs. And as the press corps tiptoed into his office following a gruesome 11–3 whomping by the St. Louis Cardinals, the tension hung over the room like a smog bank.

That’s when a young, dopey writer from the

Inquirer

decided to try to lower the stress thermometer with an illfated stab at a lighthearted question.

“Does this mean the pitchers aren’t ahead of the hitters anymore?” I asked, hoping the manager would at least get a mild chuckle out of even a meager attempt at humor.

Four seconds later, it was clear he wasn’t in the mood to attend my little Comedy Cabaret.

“(Bleep) you, Jayson,” he snapped.

There wasn’t another question asked for three minutes. Uh, no need for that—because it turned out Dallas Green had a few thoughts he needed to share. At a decibel level normally reserved for space shuttle launches. Livened up by the use of, by my count, 42 colorful words you’ll never hear on, say,

Sesame Street

.

No need to recap them all. If you’ve heard cursing before, you can imagine what much of it sounded like. But a couple of passages in this stirring monologue were so powerful, I’d be remiss not to share them with you.

On the theories (which, to be honest, were probably initiated by him) that his troops had no particular motivation to play these games to win, the manager roared:

And no, we’re not trying to lose the (bleeping) game. I’ll answer that (bleep-bleeper) before you (bleeping) guys start on it. I’m (bleeping) sick and tired of some of the (bleeping) comments I see in this (bleeping) press. You (bleep-bleepers) think we’re in this (bleeping) game for 25 (bleeping) years [and] don’t have a nickel’s worth of (bleeping) pride? The (bleep) we don’t have it.

Woo. Good one. And then there was this, one of the greatest sentences ever uttered by any manager in the history of postgame oration:

I want (bleeping) stopped all the (bleeping) (bull-bleep) about how (bleeping) (horse-bleep) this (bleeping) split (bleeping) season is. I can’t do a (bleeping) thing about that, either. You (bleep-bleepers) write what the (bleep) you want to write. But I’m sick and (bleeping) tired of reading about how the (bleeping) ballplayers are going to quit on you. The (bleeping) ballplayers won’t quit on you unless you (bleeping) guys keep hammering it in our (bleeping) heads all the time.

Wow. Awesome. But as this soliloquy came pouring out of him, I began to notice something: while I may have been the lucky guy to kick off these festivities, this clearly wasn’t aimed at me. Not in the big picture, anyway. No, this one was for his players.

Outside the door to his office, they sat at their lockers, hanging on every word. And trust me. They could hear him. At the volume level this speech was delivered, they could have heard him from the 700 level, way out in the center-field upper deck. But just to make sure they were paying attention, Dallas actually took a stroll out of his office in mid-rant, stomped into the clubhouse, looked around, and stomped back to his desk to finish his pithy remarks.

And then, once he’d vented, it was over. Period.

“Aw, it ain’t your fault, either,” he said, finally, decibels sinking with every word. “(Bleep) it. All right, let’s get down to some serious talking. What the (bleep) we got?”

And that was that. It was vintage Dallas. When his temper flared, everyone in his area code knew it. But when it was over, when he’d said what he had to say, he was a man with the remarkable ability to flip the off switch and move on. No fuss. No muss. No grudges. Not just that day. Every day. I was off his list of least-favorite media guys within minutes. We’ve been friends ever since. For three decades. A few weeks later, he even presented me with a T-shirt (actually, he threw it across the room at me). On it were the words: “(BLEEP) YOU, JAYSON.” I still have that shirt. (Don’t tell my wife.)

But I don’t need a faded T-shirt to remind me of that momentous occasion—Bleep You, Jayson Night. When I think back on it, I recall much more than those three magic words or the many lively bleep-words that followed. I think more about the man who spoke those words, and the powerful impact he had on me and everyone who crossed his path.

It would be so easy to remember Dallas Green for his vocal cords. But if you’ve been measuring this man with a volume button all these years, you’ve been making a big mistake. There’s so much more to this fellow than just a big voice. And there always has been.

Would Phillies history have been the same without him? Without the strong-willed leader who drove the 1980 Phillies all the way to the parade floats? Ask yourself that. I think you know the answer.

Would Cubs history have been the same without him? Without the tough, stubborn, relentless team president who understood that, unless the Cubs had the courage to erect light towers, the magic of Wrigley Field could never endure? I think you know that answer, too.

I’ve always believed that in this world, there are certain people who are built for certain moments. And that was Dallas Green. The perfect fit for his signature moments in time.

The battles he needed to fight weren’t for the weak or the mild-mannered. They required a strong man with strong opinions, a towering presence, and a command of every room he entered. And that, too, was Dallas Green.

If he had to accuse a bunch of Phillies who had won three division titles in a row of quitting, of not looking in the mirror, of not caring whether their team won or lost, then that’s what he had to do.

If he had to threaten to shut down Wrigley and move the Cubs to Schaumburg, Illinois, or even (shudder) to Comiskey Park, then that’s what he had to do.

If he had to stand up to George Steinbrenner’s second-guessing in the Bronx by referring to the Boss as “Manager George,” then that’s what he had to do—to salvage his pride, if not his job.

If he had to deliver a message to his superiors on the Mets by announcing it was time for Dwight Gooden “to go elsewhere” after the ace had failed his fourth drug test, then that’s what he had to do.

These were stands that very few men I’ve ever met in baseball were capable of taking. But they were made to order for Dallas Green. Always shrewd enough to understand the meaning of the moment. Never afraid of the consequences of saying or doing what that moment required.

And the true measure of his life’s work is that now, all these years later, so many of the people who felt his wrath back then are the first to tell you how much better off they are for having known him, for having their lives and careers shaped by his powerful presence.

And I’m one of them. On an August evening in 1981, I lit a fuse in Dallas Green that neither of us will ever forget. But three decades later, it’s the man who has left a lasting impact on me, not the three magic words that came out of his mouth that one night in August.

—Jayson Stark

Anyone who played, worked, or rooted for the Philadelphia Phillies during their first 95 years of existence knew heartache intimately well. As a 45-year-old man who played, worked,

and

rooted for the team at different points in my life, I guess I could count myself among the most afflicted.

As a teenager in Delaware, I pulled hard for the Phillies in the 1950 World Series against the New York Yankees. But the Whiz Kids got swept in four games.

I pitched for the 1964 Phillies team that seemed destined for an October rematch with the Yankees. But we let the National League pennant slip through our fingers in the final weeks of the season.

And I worked in the Phillies front office when the team won three consecutive division titles from 1976 to 1978. But we got eliminated each year in the National League Championship Series.

In between those near misses was a lot of futility. The Phillies carried a burden of never having won a World Series. And the weight was crushing.

That brings us to 1979, the year we all expected the weight to be lifted.

In my role as director of the minor leagues for the Phillies, I took satisfaction in seeing the emergence of players who came up through our system, guys like third baseman Mike Schmidt, shortstop Larry Bowa, left fielder Greg Luzinski, and catcher Bob Boone.

Paul Owens, our general manager, as well as my longtime friend and mentor, was the chief architect of the team. The Pope, as he was known, had supplemented our homegrown talent with smart trades and free agent signings. Ruly Carpenter, the team’s principal owner, helped out by making funds available for us to lure Pete Rose away from the Cincinnati Reds before the 1979 season. Bill Giles, the team’s vice president of business operations, sealed the deal by getting Taft Broadcasting to chip in a few bucks for the cause. Steve Carlton, a couple of years removed from a Cy Young Award, anchored a strong pitching staff.