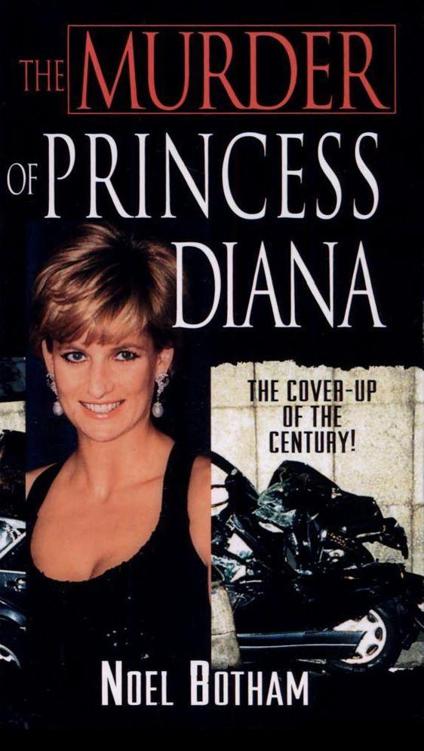

The Murder of Princess Diana

Read The Murder of Princess Diana Online

Authors: Noel Botham

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Leaders & Notable People, #Royalty, #Princess Diana, #True Accounts, #Murder & Mayhem, #True Crime, #History, #Europe, #England, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Communication & Media Studies, #Media Studies

THE

MURDER

OF

PRINCES DIANA

MURDER

OF

PRINCES DIANA

N

OEL

B

OTHAM

OEL

B

OTHAM

PINNACLE BOOKS

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

To Lesley Lewis with my love for her

constant support and encouragement

with this investigation.

constant support and encouragement

with this investigation.

PROLOGUE

After the birth of Prince Harry, Princess Diana lived with the constant fear of being murdered. She regularly warned staff and friends not to be surprised should she suddenly turn up dead.

Despite all her warnings, virtually no one imagined that Diana’s sudden, shocking death could be anything other than a tragic accident. Any lingering feelings of unease or vague suspicions about the cause of the crash were smothered by an overwhelming surge of anger, twenty-four hours later, when the French police and judiciary revealed that her driver, Henri Paul, was three times over the legal drink limit when he rammed the Mercedes into a concrete pillar. “As drunk as a pig” is how he was described, and there were traces of drugs in his blood to boot.

Newspapers around the world concluded—as they were intended to—that the culprit had been identified. A drink-sodden French chauffeur, careening along at 120 miles per hour, was the monster who had caused the death of the century’s best-loved woman.

This revelation—in my opinion, from the Paris police—was a deliberate lie. It was created in panic during a crisis meeting between senior French government officials and the head of the Paris police, who had already had reports of MI6 involvement. This meeting took place after several hours of urgent and frank talks between faceless figures in London and Paris, and their brief was to identify a simple, acceptable solution for the crash, involving a single culprit. They were to label it, categorically, an accident.

The Paris Criminal Brigade was put in charge of the investigation. Its leader, Martine Monteil, a smart and stylish fast-track career officer, had already learned that Henri Paul had worked not only for MI6 but also for French Intelligence and the French criminal investigation department

la Sûreté

. She had also been told the driver had very recently had a huge sum of money paid into his account, which could not be explained, and was carrying the equivalent of £2,000 in cash when he died.

la Sûreté

. She had also been told the driver had very recently had a huge sum of money paid into his account, which could not be explained, and was carrying the equivalent of £2,000 in cash when he died.

To the harassed police officer, under enormous pressure from the Elysée Palace, Henri Paul must have seemed the ideal scapegoat. The glaringly apparent relevance of his secondary income and his connection with the intelligence services might be downgraded if he were quickly and clearly established as the villain. She was encouraged by her superior, Paris police commander Jean-Claude Mules.

Henri Paul was their guilty man and his private life was unimportant. Monteil pursued this theory rather than the seven paparazzi photographers, under arrest since the morning of the “accident,” who had been accused of causing the crash by harassing the princess in a high-speed pursuit through the city. Bolstering this initial cover-up, Martine had already seriously discredited the first and subsequently important eyewitness. Eric Pètel would say that no photographers were following the Mercedes when it crashed. He had crawled into the back of the car alone and found the princess bleeding from her mouth and ear. The police discouraged press and television journalists from talking to this man. When he made his first report to the police, Pètel was switched to another part of Paris. They did not want him talking to the media.

In France it can be illegal for the authorities, both police and judicial, to reveal any information about an investigation until after a judge has concluded his inquiries and announced a verdict. Far from having reached a conclusion, the judge for this case had not even been appointed. Judge Hervé Stephan was only picked to head the inquiry twenty-four hours after the leak about Henri Paul’s drinking. The truth is that at this stage, thirty hours after the crash, the alleged samples of Henri Paul’s blood had not even been analyzed.

When the police did eventually come up with a blood sample which matched their claim of Paul being three times the legal drink limit, they discovered, to their extreme embarrassment, that this particular blood specimen also contained 20.7 percent carbon monoxide. This reading meant that apart from being the victim of crippling headaches and vomiting, the blood’s owner would have been virtually incapable of either walking or driving.

I have been informed by a reliable source that on that same night in Paris there was another death to be investigated: a depressed character had downed a large quantity of alcohol before attaching a hose from the exhaust of his car to the interior. The sample of this man’s blood, said my police informant at the pathology laboratory, would have had a similarly high percentage of carbon monoxide in it, a percentage equivalent to the sample purporting to be from Henri Paul. Even though the blood of this suicide case was analyzed in the same laboratory as that of the victims in Diana’s car, no official checks were ever made as to there having been a mix-up in the blood samples or some kind of cross-contamination.

The police also refused then, and still refuse today, to identify any of the other twenty-two persons classified as “investigable deaths” who were dealt with that night, or to release the pathology results of tests on their blood. It is difficult to understand their refusal if they have nothing to hide.

The pathologists involved, backed by Martine Monteil of the Criminal Brigade and the prosecutor’s office, also refused to allow independent samples to be taken from Paul’s body, or to allow independent tests on the blood and urine samples alleged to have been taken from his body during the autopsy. No outside party, including Henri Paul’s parents, was permitted to have a representative pathologist present when the body was reexamined or further samples taken of tissue or fluids. French judges have also refused to allow DNA tests to be carried out on the blood and urine samples which it was claimed came from Henri Paul’s cadaver, and so no independent positive match has been attempted. Even had such tests been permitted, there could be no guarantee that the samples produced later were actually those which the French police claim were used to obtain the original results.

In these circumstances, it is impossible to accept without question that the body in question was indeed that of Henri Paul. It might have been anyone.

No serious investigator now accepts, for many reasons, that the blood samples referred to by the police were really those of Henri Paul, even though the French authorities will not admit what seems to have been either a mistake or a blatant substitution of samples.

Other equally serious cover-ups were made by the French police and judiciary, and details of information suppressed have come to light during the seven years since the crash. A photograph of the Mercedes, taken in close-up from the front in the Alma Tunnel where it crashed, and showing Diana and Dodi laughing happily just seconds before they died, is in the official judicial files—even though police swore such photographs did not exist. They claimed that the CCTV camera near the entrance to the tunnel was switched off that night. Other reports persisted for years that that camera, and others on the route, had been deliberately turned to direct them toward the side of the road. These have now been proved to have been part of the general cover-up. A motorist who had passed through the tunnel just minutes before the crash occurred received an automatic fixed-penalty speeding notice fifteen days later. It quoted evidence from the exact camera that the police claimed had been switched off. The Paris authorities appear to be fully aware that the camera had captured pictures of Diana’s car and their lies were in danger of being exposed just weeks after the crash, but they made no public admission and have never corrected their original misleading statements. Only when the details of the speeding ticket were revealed, six years after the fateful night, did the truth become clear.

If this was a simple, straightforward accident, as they maintain, then why was it felt necessary to keep quiet about the camera? It makes no sense—unless it was part of a cover-up.

It is understood that at least one other photograph in the official judicial files—also shot through the windshield—came from another source. The police and the prosecutor’s office refuse to discuss it.

Police also denied for three weeks the existence of a small white Fiat which witnesses claimed had swerved toward Diana’s car moments before it crashed. When he did finally concede such a car might have been involved, police commander Jean-Claude Mules personally limited the search area for this car to two Parisian suburbs adjoining the tunnel where the crash occurred. When the car was discovered by independent investigators and found to have belonged to a French paparazzi photographer who had falsely denied being present in Paris on the night of the crash, the Criminal Brigade and its boss Martine Monteil apparently did not mention it to the judge. Mules told her to let it drop. He had personally interviewed the photographer, James Andanson, and declared him to be innocent of any crime.

Even after they identified this photographer as probably having worked for MI6 and other intelligence agencies, the police would still not admit he might have played a role in the accident. They claimed there was no match between his Fiat and paintwork found on the Mercedes, despite independent experts testifying that the paints were a perfect match.

Incredibly, Paris police and the investigative judge reacted mutely to the news that the photographer’s charred body had later been found in the burned-out wreckage of his car, hundreds of miles from home and in very mysterious circumstances. The car was locked but the keys were missing. The man himself was supposed to have been in a completely different part of France at the time of his death. Even with these glaring anomalies, this too was not considered worthy of further investigation by the Criminal Brigade. Local officials are unhappy with the suicide verdict which was brought in because of the lack of any conflicting evidence, but say they are willing to reopen the case if fresh evidence can be produced. Certainly there is growing speculation that he might have been dispensed of to prevent him from revealing details of the Diana assassination plot.

Why was the Paris traffic police report on the accident not given to the investigating judge, and why was the tunnel road reopened just hours after the crash and cleaned with detergent before a detailed forensic search could be made and valuable evidence preserved?

These, and many other vital facts, will be examined in detail later in this book, and will show that the crash which caused the death of Princess Diana was no accident: she was deliberately killed.

Most of the evidence points toward the security forces being responsible for the assassination. But if they planned the actual operation, on whose orders were they acting? The British government, the Americans or the royals themselves?

Princess Diana herself was never in any doubt as to who her killers would be, though in fact there was more than one group with the motive and resources for the operation. Her main enemies, she was convinced, were her husband and a sinister hard core of palace watchdogs, each under secret oath to defend the royal family against intolerable events and scandals.

Diana lived constantly with the fear of being assassinated, and put her thoughts in writing just one year before her death. She believed she was the subject of comprehensive surveillance by an unseen enemy, her destiny and that of her children in the hands of lackeys and sycophants of her husband who had tarnished her as an unbalanced paranoid.

But she believed it was Prince Charles himself who was the greatest threat. She believed he wanted her dead.

In October 1996, she wrote, “This particular phase in my life is the most dangerous. My husband is planning ‘an accident’ in my car . . . brake failure and serious head injury in order to make the path clear for him to marry.”

If Princess Diana believed this, and talked about it, then others must have known—the kind of courtier, perhaps, who would believe he would be doing the prince a great service by ridding him of this detested woman whose death was the simple key to Charles’s happiness.

The only survivor of the crash, bodyguard Trevor Rees-Jones, suffered horrendous injuries and has never been able to remember a single detail of the actual drive—though he recollects everything preceding it that night. His main fear is that his memory will return. “If I remember, they will kill me,” he said. “Every single day I fear for my life.”

What is there in his subconscious that is prompting such real fear in his conscious mind? Or has he already remembered what he saw in those last few moments before the crash, and will not admit to it because to do so would be like signing his own death warrant?

The less-than-loyal butler Paul Burrell also feared attempts on his life by “the dark forces at work in the country.” There are those, he believes, who want to prevent him revealing further royal secrets which he claims pose an even greater threat to the future of the royal family than those already published.

Princess Diana’s terror was so real that when she lost her HRH status after her divorce from Prince Charles, she refused a police personal protection squad despite considerable pressure from the palace. Isolated, vulnerable and believing herself to be constantly at risk, she was convinced an assassination attempt would almost certainly be made by the British security forces, which include the royal protection squad, made up of some of the very people she feared.

She had also been warned by diplomat friends in Washington that she was a possible target for American security “laundrymen,” whose cleanup technique involves the ultimate sanction of assassination. Many American politicians and law-enforcement officers believe that when President John F. Kennedy publicly committed himself, in the summer of 1963, to withdrawing every American serviceman from Vietnam by Christmas, it was tantamount to signing his own death warrant. Too many unscrupulous men were making too much money from the war to want it ended. Then, as now, there could be no profit in peace for men like these. His successor, Lyndon Johnson, proved it by sending a further 250,000 American troops to Vietnam.

Other books

Manly Wade Wellman - John the Balladeer SSC by John the Balladeer (v1.1)

The Do Over by A. L. Zaun

Bad Heir Day by Wendy Holden

The Agathon: Reign of Arturo by Colin Weldon

Set Me Alight by Leviathan, Bill

Blood Cruise: A Deep Sea Thriller by Jake Bible

The Cowboy Meets His Match by Leann Harris

Finally His by Emma Hillman

In Flames by Richard Hilary Weber

Mistletoe & Murder by Laina Turner