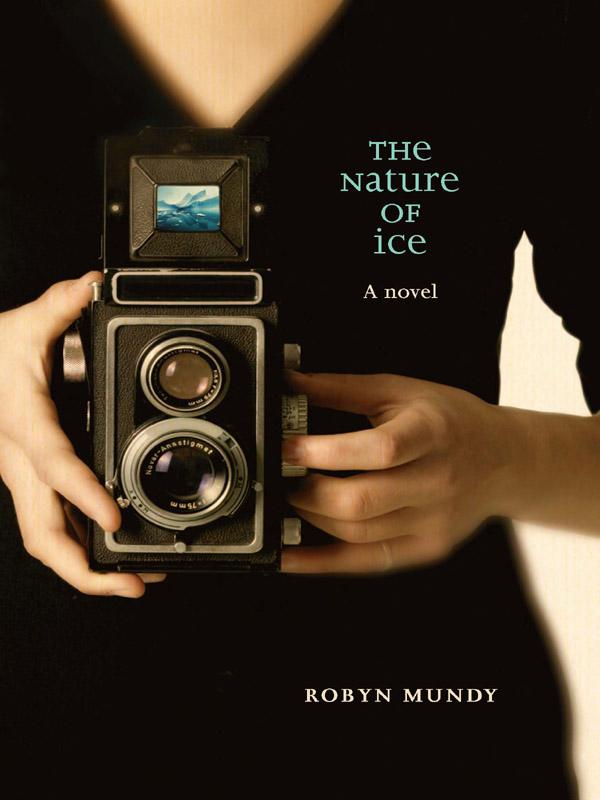

The Nature of Ice

IT WAS OVER A DECADE ago that Robyn Mundy first went to Antarctica, and she has managed to return there every year since, working as an assistant expedition leader for a Sydney-based eco-tour company. In the summer of 2003â04, she spent a season living and working at Davis Station, Antarctica, as a field assistant. In 2008 she over-wintered at Mawson Station, Antarctica, where she worked on an emperor penguin project. Robyn has a Masters Degree in Creative Writing from the University of New Mexico, USA . She wrote

The

Nature of Ice

as part of a PhD in Writing at Edith Cowan University in Western Australia.

TH

e

N

ature O

F

ice

ROBYN MUNDY

First published in 2009

Copyright © Robyn Mundy 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian

Copyright Act

1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory board.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web:

www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au

978 1 74175 576 3

Set in 12.5/16.25 pt Garamond Premier Pro by Bookhouse, Sydney

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Nancy Robinson Flannery, with love and admiration

CONTENTS

MISSPELLINGS AND ORIGINAL PUNCTUATION in the archival material have been retained.

After Antarctica, nothing is the same . . .

â

T

HOMAS

K

ENEALLY

,

2003

Tasmanian Club, Hobart

2 December 1911

THE SCENT OF BLOSSOM CAUGHT the night breeze and drifted into his room. He stood naked in the darkness. Beyond the open window a bow of streetlights; far away, a mopoke owl. On this, his final night in the known world, he tried to imprint on his memory each sound, each smell, the lightness of summer, the touch of air against his skin. He imagined Paquita's tortoiseshell clip falling to the floor. He had never seen her dark hair loose.

Mercury

newspaper,

4 December 1911

The Antarctic Expedition

T

he

Aurora

sailed from Hobart for Antarctica via Macquarie Island on Saturday afternoon, having on board Dr Mawson and nearly half the members of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, the scientific instruments, and wireless telegraphy equipment, a large quantity of stores of all kinds, provisions, clothing, sledges, 266 tons of coal, etc. She is to proceed direct to Macâquarie Island, where the party which is to remain on the island will be landed . . .

Hearty cheers were given by those on shore as the vessel drew away, and these were answered by the occupants of the

Aurora

, while there was much waving of hats and handkerchiefs. Cameras were busy in all directions, and the cinematographs were not idle, so that the memory of the departure of the first Australasian Antarctic Expedition from Hobart should not be lost as long as pictorial records can preserve it. Occupying a prominent position on the

Aurora

's rigging was a signboard with a finger pointing ahead, supplied by the Tasmanian Tourist Association, bearing the words “To the Antarctic and Success”.

AURORA AUSTRALIS

YAWS IN THE roll of the storm, four days out from Hobart and hurtling southward beyond the edge of the known world. Freya's world, that is. During the night the cabin has turned into a dance floor for Blundstone boots, a fluffy seal, an empty water bottle missing its cap. As if in an act of surrender, a drawer flings open and jettisons a roll of large format film. Freya Jorgensen watches from the top bunk as it tumbles over carpet to join the motley collection.

From along the hallway, sounds of retching spill from a cabin. A tingle rises through Freya's jaw and spreads across her lips as she teeters on the edge of nausea. If she could only open the porthole, stand before the moonlit night and draw in great gasps of cold ocean air. Her stomach rises and falls like an untethered buoy, its rhythmic wave keeping time with the curtains that fringe each bunk and glide freely on their tracks. She wedges her body diagonally and determines again to concentrate on breathing, dismiss each new thought that entices distraction. She weighs up the energy required to maintain purchase on her bunk with that of abandoning sleep and escaping the cabin altogether. Her travel clock reads 2:20 a.m., forty minutes since the last time she looked. She gives sleep one more chance, though she knows a lost cause when she sees it.

FREYA REELS ALONG THE SHIP'S corridor, out through the heavy double doors and onto the covered stern deck where she pulls on gloves and zips a padded jacket over her pyjamas. She leans against the railing above the trawl deck and looks out at the rolling mountain of ocean lit by the floodlights of the ship. With the wind screaming and steel groaning, the ship ought to tear in two, continually pummelled and pulled by the yank of the storm. Yet she feels secure aboard this ice-strengthened vessel, her feelings a contrast to the mix of dread and excitement she remembers as a childâseesawing across oceans and hemispheres to a strange southern land.

Flood lamps bathe the protected surrounds with an amber glow that drains the hurry from the ship's lurid orange paint. Freya relishes the mood of this working deck where few stay longer than to smoke a cigarette. In the roughest seas she can stand at eye level with the ocean and watch wind peel back the caps. In daylight hours she photographs albatross and petrels wheeling across the wake, their wing tips skimming the waves with a precision that astounds her. How easy it would be to mistime the peak of the swell, to fly too low, to flounder. And yet the sea birds toy with the ocean, spiralling upward, weaving in great playful arcs, circling the ship time and again.

Aurora Australis

slides into a trough and shudders to a standstill. A wave of vibration stutters down its spine, reverberating through her hands and feet. Before the ship has time to regain momentum, a new crest of water gallops forward, lifting the hull on its shoulders.

Freya moves to the first run of steps leading down to the trawl deck, but even from here she sees how easily she could lose her footing in a roll. She grips the handrail and leans out into the night.

It takes time for her eyes to grow accustomed to the dark, to realise that what she took for cloud-covered moonlight is something else again. The movement is subtle at first, little more than a mystical shroud tinted with the softest hush of green. The wisp of colour begins to swell, its edges inhaling and exhaling like a creature stirring into life. She has an image, fleeting, of lying beneath such a sky roiling with emerald and gold. But Freya is not inclined to rely on childhood memories; her first eight years are filtered through the countless recollections of her mother who, after three decades in Western Australia, still yearns for the seeming perfection of their Norwegian homeland. Is she so very different from Mama, always wanting more?

âWilling us to get there faster?'

The man pauses at the top railing before walking down the steps. Adam Singer is one of the carpenters heading to Davis Station. A few of the younger girls have been talking about him and Freya understands why: drop-dead gorgeous is right.

âDidn't mean to startle you.'

His gaze disarms her, and though it seems foolishâa married woman of thirty-sixâshe suddenly feels unsure of herself. âDo you think that's an aurora out there?'

Adam leans into her side and nods. âFirst time south?'

âIs it that obvious?' She smiles. âI still can't believe I'm on my way to Antarctica. That it's not a dream.'

âA year-long dream. If Davis is like Macquarie Island we'll have plenty of good auroras through winter.'

âI'll have to find a way to come back. I'm only down for summer.'

âThat's a shame.'

The ship heaves and jolts. Freya grabs for the handrail but misses. She feels herself teeter backward, stopped by Adam who snags her waist. A rush of ocean cascades over the stern and jams open the trawl gates with a deafening ring. Beneath the gridded steps they stand upon, water floods the deck. Adam does not loosen his hold and she in turn lingers, registering, in this surreal light, the invitation proffered. As intimately as a lover, he combs back threads of her white-blonde hair blown across her face while she stands mesmerised, leaning towards his touch. With an air of fascination Adam traces his finger around the birthmark that spreads across her cheek like a stain. Perhaps his blatant trespass onto tainted skin, perhaps her own returning sanity, makes her break away, her discomposure heightened by the hardness in his eyes.