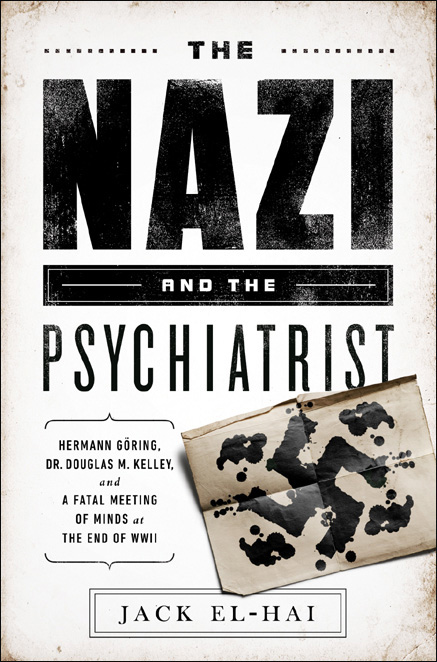

The Nazi and the Psychiatrist

Read The Nazi and the Psychiatrist Online

Authors: Jack El-Hai

T

HE

N

AZI AND THE

P

SYCHIATRIST

Copyright © 2013 by Jack El-Hai.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs™, a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail

[email protected]

.

Book Design by Timm Bryson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

El-Hai, Jack.

The Nazi and the psychiatrist : Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a fatal meeting of minds at the end of WWII / Jack El-Hai.—First Edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61039-157-3 (e-book)

1. Göring, Hermann, 1893–1946—Psychology. 2. Kelley, Douglas M. (Douglas McGlashan), 1912–1958. 3. Nazis—Psychology. 4. War criminals—Germany—Psychology. 5. Nuremberg Trial of Major German War Criminals, Nuremberg, Germany, 1945–1946. 6. Nuremberg War Crime Trials, Nuremberg, Germany, 1946–1949. 7. Nazis—Germany—Biography. 8. Psychiatrists—United States—Biography. I. Title.

DD247.G67E4 2014

341.6'90268—dc23

2013010730

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

TO ESTELLE EL-HAI AND DR. ARNOLD E. ARONSON

with my love and gratitude

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

The House

CHAPTER 2

Mondorf-les-Bains

CHAPTER 3

The Psychiatrist

CHAPTER 4

Among the Ruins

CHAPTER 5

Inkblots

CHAPTER 6

Interloper

CHAPTER 7

The Palace of Justice

CHAPTER 8

The Nazi Mind

CHAPTER 9

Cyanide

CHAPTER 10

Post Mortem

Photo insert between pages 134–135

NUREMBERG JAIL STAFF

Col. Burton Andrus, commandant

Capt. John Dolibois, welfare officer

Lt. Gustave Gilbert, psychologist

Maj. Douglas McGlashan Kelley, psychiatrist

Howard Triest, translator

NUREMBERG DEFENDANTS

Karl Dönitz, admiral and Hitler’s designated successor

Hans Frank, governor-general of Nazi-occupied Poland

Wilhelm Frick, head of the radio division, German Propaganda Ministry

Walther Funk, minister of economics

Hermann Göring, Reichsmarschall and Luftwaffe chief

Rudolf Hess, deputy to the Führer

Alfred Jodl, chief of operations for the German High Command

Ernst Kaltenbrunner, chief of security police

Wilhelm Keitel, chief of staff of the German High Command

Robert Ley, head of the German Labor Front

Konstantin von Neurath, minister of foreign affairs (until 1938)

Franz von Papen, German vice chancellor

Erich Raeder, commander in chief of the German navy

Joachim von Ribbentrop, foreign minister

Alfred Rosenberg, Nazi party philosopher and Reichsminister for the Eastern Occupied Territories

Fritz Sauckel, chief of slave labor recruitment

Hjalmar Schacht, Reichsbank president and minister of economics (until 1937)

Baldur von Schirach, Hitler Youth leader

Arthur Seyss-Inquart, Austrian chancellor and Reich commissioner for the Netherlands

Albert Speer, Reichsminister for armaments and munitions

Julius Streicher, editor of

Der Stürmer

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL OFFICIALS

William “Wild Bill” Donovan, special assistant to the chief prosecutor

Robert Jackson, US chief of counsel for the prosecution

Judge Geoffrey Lawrence, president of the court

FAMILY OF DOUGLAS MCGLASHAN KELLEY

Charles McGlashan, grandfather

June McGlashan Kelley, mother

George “Doc” Kelley, father

Alice Vivienne “Dukie” Hill Kelley, wife

Doug, Alicia, and Allen Kelley, children

T

he Kelleys lived in a sprawling, Mediterranean-style villa on Highgate Road in the hills of Kensington, north of Berkeley, California. Its red-tiled roof rose high above the distant, drifting waters of the bay, but closer, beyond the yard’s four terraces and stone walks and down a slope of redwood and fruit trees, stood the headstones of Sunset View Cemetery.

A little merry-go-round and a children’s swimming pool sat in the center courtyard of the Kelleys’ U-shaped house. The front door opened onto a hallway with the kitchen to the left, where the doctor made the family’s meals using a large oven, a fast-food griddle, and a meat grinder. The kitchen connected to a pantry with a freezer. The oldest son once sat atop the humming appliance and contemplated killing his father with an ax.

The entry hallway led to a bathroom on the right—the site of a gruesome scene that played out on the first day of 1958—and beyond that to the living room, which contained a fireplace, a long sofa, and the doctor’s own green leather chair. The room was carpeted, with the furniture pushed against the walls to open space for guests. Sometimes Dr. Kelley would play a game there with his oldest son. The boy had to leave the room, and in his absence the doctor would move a pencil on the coffee table. When the boy returned, he had to figure out what had changed.

Beyond the living room was Dr. Kelley and Dukie’s bedroom, overlooking the rear of the half-acre lot. In a small closet that the children sneaked into through a hallway, they could overhear their parents’ fights.

From the living room, black-stained stairs rose to the second level. Up there a bullet hole, hidden beneath a rug, scarred the wooden floor of a hallway drenched with sunlight from tall windows. Before terminating at Dr. Kelley’s office, the hallway ran past a closet concealing the magic tricks and props for his shows.

The view from the office window presented a glorious panorama of the Golden Gate bay and the prison tower of Alcatraz Island. When Dr. Kelley turned his desk chair to face the view, he may have settled his gaze on Alcatraz and remembered his months working in another prison, in Nuremberg. His desk was orderly. In cabinets and a small laboratory he kept bone saws, a lab table, mortars, alcohol burners, graduated cylinders and beakers, collections of crystals, botanical samples mounted on glass slides, two human skulls, and a large assortment of chemicals, many of them toxic.

The children slept in the basement bedrooms. They dreaded the unpredictability of Dr. Kelley’s goodnight visits. When they heard the creak of his weight on the stairs, they had a few seconds to brace themselves for whatever mood he was in.

The last argument began in the kitchen. Often when Dr. Kelley and Dukie fought, she would pack her purse and leave for the day. This time Dr. Kelley burst out of the kitchen howling and stormed up the stairs to his office. He slammed the door, toppling a porcelain doorstop, its fragments raining down the steps. After a couple of minutes he emerged, concealing something in his hand. He came down the stairs and stopped on the landing, which commanded the living room like a stage. He shouted a statement that terrified and bewildered his wife, father, and children. Then he put something in his mouth and swallowed.

T

he airplane, a little Piper L-4, couldn’t budge. Its sole passenger, Hermann Göring—former World War I ace, chief of the once fearsome Luftwaffe, and highest-ranking official of the Third Reich left alive—weighed too much for a safe takeoff.

This was an unaccustomed lull for Göring. For weeks he had been in a state of continual movement, uncertainty, and danger.

He had evacuated his beloved hunting retreat and party estate, Carinhall. He had endured forced confinement at Adolf Hitler’s order after offering, heroically in his view, to take control of the Nazi government. Soon afterward Göring learned of Martin Bormann’s command to German forces to murder him, and he scrambled away from the custody of the Schutzstaffel (SS).

Less than forty-eight hours before boarding the Piper, on the day before Germany’s surrender, May 7, 1945, Göring had sent a letter across the disintegrating line of battle to the US military command. He acknowledged Nazi Germany’s imminent collapse and offered to help the Allies form a new government of the Reich. US Army Brigadier General Robert I. Stack marveled at the sender’s audacity and was soon leading a convoy of soldiers in jeeps to capture him. They caught up with Göring’s own procession of vehicles near the Austrian town of Radstadt. Göring was riding in a Mercedes-Benz equipped with bulletproof glass.

The chauffeur nudged Göring and said, “Here are the Americans, Herr Reichsmarschall.” Leaning toward his wife, Emmy, Göring said, “I have a

good feeling about this.” Stack emerged from a US Army car, and the men exchanged salutes. Göring and his wife, once one of the most powerful couples in Europe, had reached the end of their war.

Emmy was in tears. This meeting with enemy officers on a road congested with refugees “was certainly an extremely painful moment for us,” she later wrote.

Stack telephoned the field office of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Europe, with news of Göring’s capture. Göring, who

considered himself the most charismatic and internationally admired of the German leaders, believed Eisenhower would soon order his release.

American soldiers escorted Göring and his family to Castle Fischorn near Zell am See, where Göring joked with his captors as his family settled into rooms on the second floor and ate dinner with Stack. Göring told Emmy that he would leave the following day for his meeting with Eisenhower, but that he would soon return to her.

“Don’t worry if I’m away for a day or two longer,” he said to her. After some reflection, he added, “To tell the truth, I feel that things will be all right. Don’t you think so?”

Göring spent the night at the headquarters of the US Seventh Army at Kitzbühl, where he again asked for safe conduct and a meeting with Eisenhower. His captors told Göring it was unlikely such a meeting would ever happen.

Yet Stack and his staff extended many courtesies to Göring: the Nazi leader drank champagne during receptions with American soldiers, posed for photographs and held a press conference, and was treated for one last time as the high-ranking representative of state that he believed himself to be.