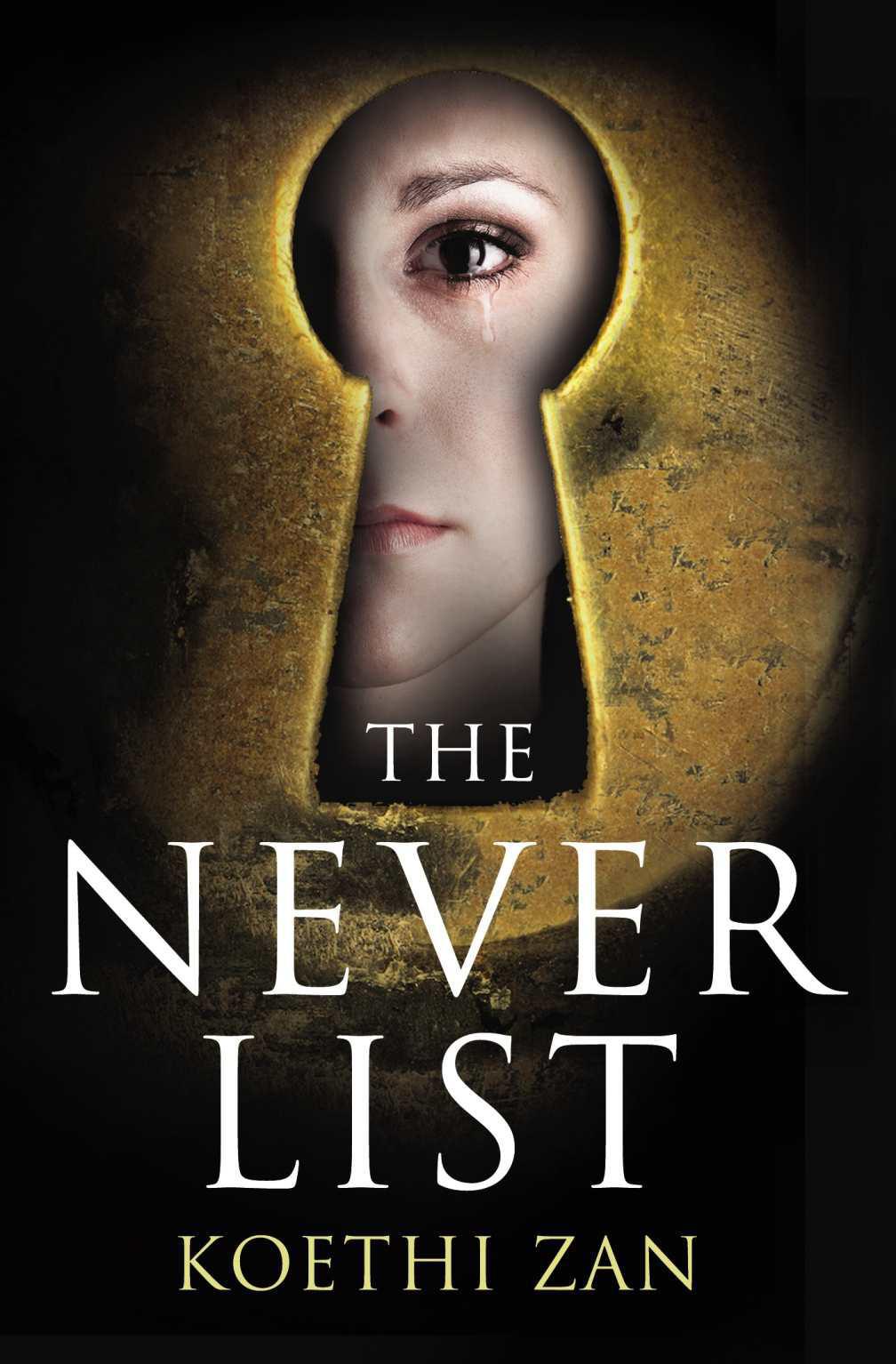

The Never List

Authors: Koethi Zan

Contents

About the Book

NEVER GET IN THE CAR

For years, best friends Sarah and Jennifer kept what they called the ‘Never List’: a list of actions to be avoided, for safety’s sake, at all costs. But one night, they failed to follow their own rules.

NEVER GO OUT ALONE AFTER DARK

Sarah has spent ten years trying to forget her ordeal. But now the FBI has news that forces her to confront her worst fears.

NEVER TAKE RISKS

If she is to uncover the truth about what really happened to Jennifer, Sarah needs to work with the other women who shared her nightmare. But they won’t be happy to hear from her. Because down there in the dark, Sarah wasn’t just a victim.

NEVER TRUST ANYONE

About the Author

Koethi Zan was born and raised in rural Alabama. She attended Yale Law School and currently lives in an old farmhouse in upstate New York.

The Never List

is her first novel.

For E.E.B., who always believed

“Human beings are so terrible.… They can bear anything.”

—From the film

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant

,

Rainer Werner Fassbinder, director and screenwriter

CHAPTER 1

There were four of us down there for the first thirty-two months and eleven days of our captivity. And then, very suddenly and without warning, there were three. Even though the fourth person hadn’t made any noise at all in several months, the room got very quiet when she was gone. For a long time after that, we sat in silence, in the dark, wondering which of us would be next in the box.

Jennifer and I, of all people, should not have ended up in that cellar. We were not your average eighteen-year-old girls, abandoning all caution once set loose for the first time on a college campus. We took our freedom seriously and monitored it so carefully, it almost didn’t exist anymore. We knew what was out there in that big wide world better than anyone, and we weren’t going to let it get us.

We had spent years methodically studying and documenting every danger that could possibly ever touch us: avalanches, disease,

earthquakes, car crashes, sociopaths, and wild animals—all the evils that might lurk outside our window. We believed our paranoia would protect us; after all, what are the odds that two girls so well versed in disaster would be the ones to fall prey to it?

For us, there was no such thing as fate.

Fate

was a word you used when you had not prepared, when you were slack, when you stopped paying attention. Fate was a weak man’s crutch.

Our caution, which verged on a mania by our late teens, had started six years earlier when we were twelve. On a cold but sunny January day in 1991, Jennifer’s mother drove us home from school, the same as every other weekday. I don’t even remember the accident. I only recall slowly emerging into the light to the beat of the heart monitor, as it chirped out the steady and comforting rhythm of my pulse. For many days after that, I felt warm and utterly safe when I first woke up, until that moment when my heart sank and my mind caught up with time.

Jennifer would tell me later that she remembered the crash vividly. Her memory was typically post-traumatic: a hazy, slow-motion dream, with colors and lights all swirling together in a kind of operatic brilliance. They told us we were lucky, having been only seriously injured and living through the ICU, with its blur of doctors, nurses, needles, and tubes, and then four months recovering in a bare hospital room with CNN blaring in the background. Jennifer’s mother had not been lucky.

They put us in a room together, ostensibly so we could keep each other company for our convalescence, and as my mother told me in a whisper, so I could help Jennifer through her grief. But I suspected the other reason was that Jennifer’s father, who was divorced from her mother and an erratic drunk we had always taken pains to avoid, was only too happy when my parents volunteered to take turns sitting with us. At any rate, as our bodies slowly healed, we were left alone more often, and it was then that we

started the journals—to pass the time, we said to ourselves, both probably knowing deep down that it was in fact to help us feel some control over a wild and unjust universe.

The first journal was merely a notepad from our bedside table at the hospital, with J

ONES

M

EMORIAL

printed in Romanesque block letters across the top. Few would have recognized it as a journal, filled as it was only with lists of the horrors we saw on television. We had to ask the nurses for three more notepads. They must have thought we were filling our days with tic-tac-toe or hangman. In any event, no one thought to change the channel.

When we got out of the hospital, we worked on our project in earnest. At the school library, we found almanacs, medical journals, and even a book of actuarial tables from 1987. We gathered data, we computed, and we recorded, filling up line after line with the raw evidence of human vulnerability.

The journals were initially divided into eight basic categories, but as we got older, we learned with horror how many things there were that were worse than P

LANE

C

RASHES

, H

OUSEHOLD

A

CCIDENTS

, and C

ANCER

. In stone silence and after careful deliberation, as we sat in the sunny, cheerful window seat of my bright attic bedroom, Jennifer wrote out new headings in bold black letters with her Sharpie: A

BDUCTION

, R

APE

, and M

URDER

.

The statistics gave us such comfort. Knowledge is power, after all. We knew we had a one-in-two-million chance of being killed by a tornado; a one-in-310,000 chance of dying in a plane crash; and a one-in-500,000 chance of being killed by an asteroid hitting Earth. In our warped view of probability, the very fact that we had memorized this endless slate of figures somehow changed our odds for the better. Magical thinking, our therapists would later call it, in the year after I came home to find all seventeen of the journals in a pile on our kitchen table, and both my parents sitting there waiting with tears in their eyes.

By then I was sixteen, and Jennifer had come to live with us full time because her father was in jail after his third DUI. We visited him, taking the bus because we had decided it wasn’t safe for us to drive at that age. (It would be another year and a half before either of us got a license.) I had never liked her father, and it turned out she hadn’t either. Looking back, I don’t know why we visited him at all, but we did, like clockwork, on the first Saturday of every month.

Mostly he just looked at her and cried. Sometimes he would try to start a sentence, but he never got very far. Jennifer didn’t bat an eye, just stared at him with as blank an expression as I ever saw on her face, even when we were down in that cellar. The two of them never spoke, and I sat a little away from them, fidgeting and uncomfortable. Her father was the only thing she would not discuss with me—not one word—so I just held her hand on the bus back home each time, while she gazed out the window in silence.

The summer before we went to off to Ohio University, our anxieties reached a fever pitch. We would soon be leaving my attic room, which we shared, and go into the vast unknown: a college campus. In preparation, we made the Never List and hung it on the back of our bedroom door. Jennifer, who was plagued by insomnia, would often get up in the middle of the night to add to it: never go to the campus library alone at night, never park more than six spaces from your destination, never trust a stranger with a flat tire. Never, never, never.

Before we left, we meticulously packed a trunk, filling it with the treasures we had collected over the years at birthdays and Christmases: face masks, antibacterial soap, flashlights, pepper spray. We chose a dorm in a low building so that, in the event of fire, we could easily make the jump. We painstakingly studied the campus map and arrived three days early to examine the footpaths and walkways to evaluate for ourselves the lighting, visibility, and proximity to public spaces.

When we arrived at our dorm, Jennifer took out her tools before we had even unpacked our bags. She drilled a hole in our window sash, and I inserted small but strong metal bars through the wood, so it couldn’t be opened from the outside even if the glass was broken. We kept a rope ladder by the window, along with a set of pliers to remove the metal bars in the event we needed a quick escape. We got special permission from campus security to add a deadbolt lock to our door. As a final touch, Jennifer gingerly hung the Never List on the wall between our beds, and we surveyed the room with satisfaction.

Maybe the universe played out a perverse justice on us in the end. Or maybe the risks of living in the outside world were simply greater than we had calculated. In any event, I suppose we stepped out of our own bounds by trying to live a semblance of regular college life. Really, I thought later, we knew better. But at the same time the lure of the ordinary proved to be too irresistible. We went to classes separately from each other even if we had to go to opposite ends of the campus. We stayed in the library talking to new friends well after dark sometimes. We even went to a couple of campus mixers sponsored by the university. Just like normal kids.

In fact, after only two months there, I secretly began thinking we could start living more like other people. I thought maybe the worries of our youth could be put away, packed safely in the cardboard boxes back home where we stored our other childhood memorabilia. I thought, in what I now see as a heretical break from everything we stood for, that maybe our juvenile obsessions were just that, and we were finally growing up.

Thankfully, I never articulated those thoughts to Jennifer, much less acted on them, so I was able to half forgive myself for them in those dark days and nights to follow. We were just college kids, doing what college kids do. But I could comfort myself knowing we had followed our protocols to the bitter end. We had, almost

automatically, executed our protective strategies with a military precision and focus, every day a continuous safety drill. Every activity had a three-point check, a rule, and a backup plan. We were on our guard. We were careful.