Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The New Penguin History of the World (100 page)

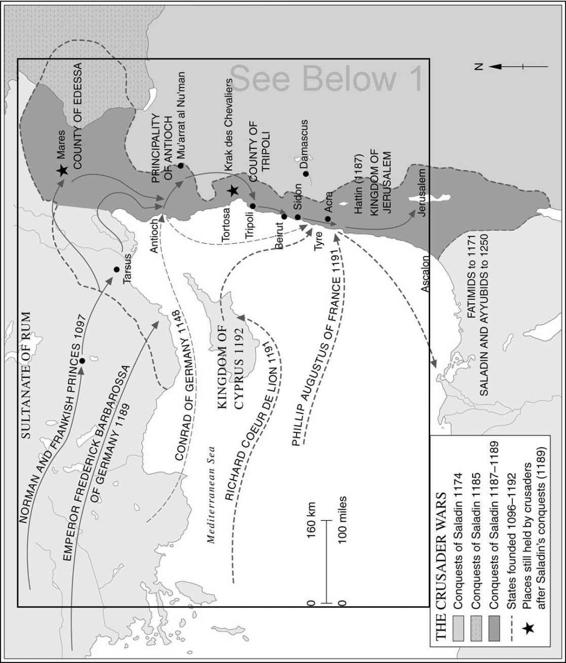

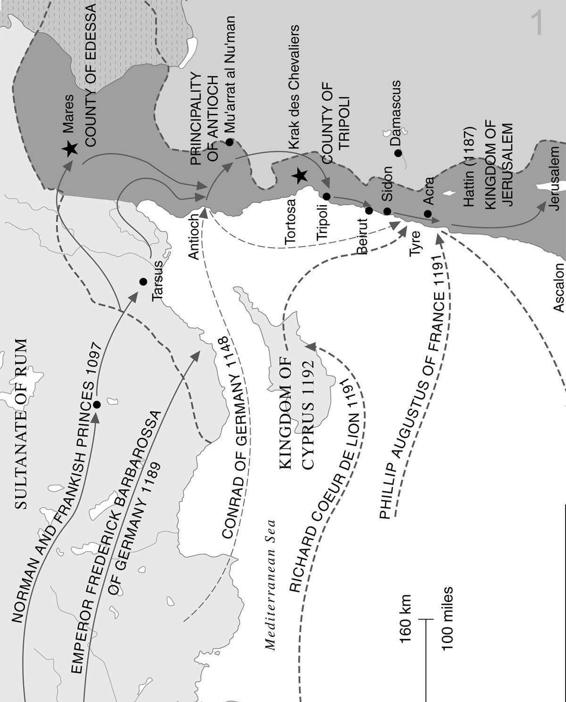

Several more crusades set out in the thirteenth century, but though they helped to put off a little longer the dangers which faced Byzantium, the last Christian stronghold in Palestine, Acre, fell to the Muslims in 1281 and thereafter crusading to the Holy Land was dead as an independent force. Religious impulse could still move men, but the first four crusades had too often shown the unpleasant face of greed. They were the first examples of European overseas imperialism, both in their characteristic mixture of noble and ignoble aims and in their abortive settler colonialism. Whereas in Spain, and on the pagan marches of Germany, Europeans were pushing forward a frontier of settlement, they tried in Syria and Palestine to transplant western institutions to a remote and exotic setting as well as to seize lands and goods no longer easily available in the West. They did this with clear consciences because their opponents were infidels who had by conquest installed themselves in Christianity’s most sacred shrines. ‘Christians are right, pagans are wrong’, said the

Song of Roland

and that probably sums up well enough the average crusader’s response to any qualms about what he was doing.

The brief successes of the first crusade owed much to a passing phase of weakness and anarchy in the Islamic world. The feeble transplants of the Frankish states and the Latin empire of Constantinople would not last. But there were to be more enduring results, above all in the relations of Christianity and Islam, creating for centuries a sense of unbridgeable ideological separation between the two faiths. What one scholar has well called a ‘flood of misrepresentation’ of Islam was well under way in western Christendom early in the twelfth century. Among other things it ended the possibility of the two religions living side by side, as they had sometimes done in Spain, as well as halting the corrosion of Christian culture there by Muslim learning. But the division of Christendom was embittered, too,

by the crusades; the sack of Constantinople had been the work of crusaders. The crusades had a legacy, moreover, in a new temper in western Christianity, a militant tone and an aggressiveness which would often break out in centuries to come (when it would also be able to exploit technological superiority). In it lay the roots of a mentality which, when secularized, would power the world-conquering culture of the modern era. The Reconquest was scarcely to be complete before the Spanish would look to the Americas for the battlefield of a new crusade.

Yet Europe was not impervious to Islamic influence. In these struggles she imported and invented new habits and institutions. Wherever they encountered Islam, whether in the crusading lands, Sicily or Spain, western Europeans found things to admire. Sometimes they took up luxuries not to be found at home: silk clothes, the use of perfumes and new dishes. One habit acquired by some crusaders was that of taking more frequent baths. This may have been unfortunate, for it added the taint of religious infidelity to a habit already discouraged in Europe where bath-houses were associated with sexual licence. Cleanliness had not yet achieved its later quasi-automatic association with godliness.

One institution crystallizing the militant Christianity of the high Middle Ages was the military order of knighthood. It brought together soldiers who professed vows as members of a religious order and of an accepted discipline to fight for the faith. Some of these orders became very rich, owning endowments in many countries. The Knights of St John of Jerusalem (who are still in existence) were to be for centuries in the forefront of the battle against Islam. The Knights Templar rose to such great power and prosperity that they were destroyed by a French king who feared them, and the Spanish military orders of Calatrava and Santiago were in the forefront of the Reconquest.

Another military order operated in the north, the Teutonic Knights, the warrior monks who were the spearhead of Germanic penetration of the Baltic and Slav lands. There, too, missionary zeal combined with greed and the stimulus of poverty to change both the map and the culture of a whole region. The colonizing impulse which failed in the Near East had lasting success further north. German expansion eastwards comprised a huge folk-movement, a centuries-long tide of men and women clearing forest, planting homesteads and villages, founding towns, building fortresses to protect them and monasteries and churches to serve them. When the crusades were over, and the narrow escape from the Mongols had reminded Europe that it could still be in danger, this movement went steadily on. Out on the Prussian and Polish marches, the soldiers, among whom the Teutonic Knights were outstanding, provided its shield and

cutting edge at the expense of the native peoples. This was the beginning of a cultural conflict between Slav and Teuton which persisted down to the twentieth century. The last time that the West threw itself into the struggle for Slav lands was in 1941: many Germans saw ‘Barbarossa’ (as Hitler’s attack on Russia was named in memory of a medieval emperor) as another stage in a centuries-old civilizing mission in the East. In the thirteenth century a Russian prince, Alexander Nevsky, grand duke of Novgorod, had to beat off the Teutonic Knights (as Russians were carefully reminded by a great film in 1937) at a moment when he also faced the Tatars on another front.

While the great expansion of the German East between 1100 and 1400 made a new economic, cultural and racial map, it also raised yet another barrier to the union of the two Christian traditions. Papal supremacy in the West made the Catholicism of the late medieval period more uncompromising and more unacceptable than ever to Orthodoxy. From the twelfth century onwards Russia was more and more separated from western Europe by her own traditions and special historical experience. The Mongol capture of Kiev in 1240 had been a blow to eastern Christianity as grave as the sack of Constantinople in 1204. It also broke the princes of Muscovy. With Byzantium in decline and the Germans and Swedes on their backs, they were to pay tribute to the Mongols and their Tatar successors of the Golden Horde for centuries. This long domination by a nomadic people was another historical experience sundering Russia from the West.

Tatar domination had its greatest impact on the southern Russian principalities, the area where the Mongol armies had operated. A new balance within Russia appeared; Novgorod and Moscow acquired new importance after the eclipse of Kiev, though both paid tribute to the Tatars in the form of silver, recruits and labour. Their emissaries, like other Russian princes, had to go to the Tatar capital at Sarai on the Volga, and make their separate arrangements with their conquerors. It was a period of the greatest dislocation and confusion in the succession patterns of the Russian states. Both Tatar policy and the struggle to survive favoured those which were most despotic. The future political tradition of Russia was thus now shaped by the Tatar experience as it had been by the inheritance of imperial ideas from Byzantium. Gradually Moscow emerged as the focus of a new centralizing trend. The process can be discerned as early as the reign of Alexander Nevsky’s son, who was prince of Muscovy. His successors had the support of the Tatars, who found them efficient tax-gatherers. The Church offered no resistance and the metropolitan archbishopric was transferred from Vladimir to Moscow in the fourteenth century.

Meanwhile, a new challenge to Orthodoxy had arisen in the West. A Roman Catholic but half-Slav state had emerged, which was to hold Kiev for three centuries. This was the medieval duchy of Lithuania, formed in 1386 in a union by marriage which incorporated the Polish kingdom and covering much of modern Poland, Prussia, the Ukraine and Moldavia. Fortunately for the Russians, the Lithuanians fought the Germans, too; it was they who shattered the Teutonic Knights at Tannenberg in 1410. Harassed by the Germans and the Lithuanians to the west, Muscovy somehow survived by exploiting divisions within the Golden Horde.

The fall of Constantinople brought a great change to Russia; eastern Orthodoxy had now to find its centre there, and not in Byzantium. Russian churchmen soon came to feel that a complex purpose lay in such awful events. Byzantium, they believed, had betrayed its heritage by seeking religious compromise at the Council of Florence. ‘Constantinople has fallen’, wrote the Metropolitan of Moscow, ‘because it has deserted the true Orthodox faith… There exists only one true Church on earth, the Church of Russia.’ A few decades later, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, a monk could write to the ruler of Muscovy in a quite new tone: ‘Two Romes have fallen, but the third stands and a fourth will not be. Thou art the only Christian sovereign in the world, the lord of all faithful Christians.’

The end of Byzantium came when other historical changes made Russia’s emergence from confusion and Tatar domination possible and likely. The Golden Horde was rent by dissension in the fifteenth century. At the same time, the Lithuanian state began to crumble. These were opportunities, and a ruler who was capable of exploiting them came to the throne of Muscovy in 1462. Ivan the Great (Ivan III) gave Russia something like the definition and reality won by England and France from the twelfth century onwards. Some have seen him as first national ruler of Russia. Territorial consolidation was the foundation of his work. When Muscovy swallowed the republics of Pskov and Novgorod, his authority stretched at least in theory as far as the Urals. The oligarchies which had ruled them were deported, to be replaced by men who held lands from Ivan in return for service. The German merchants of the Hanse who had dominated the trade of these republics were expelled, too. The Tatars made another onslaught on Moscow in 1481 but were beaten off, and two invasions of Lithuania gave Ivan much of White Russia and Little Russia in 1503. His successor took Smolensk in 1514.

Ivan the Great was the first Russian ruler to take the title of ‘Tsar’. It was a conscious evocation of an imperial past, a claim to the heritage of the Caesars, the word from which it originated. In 1472 Ivan married a niece of the last Greek emperor. He was called ‘autocrat by the grace of God’ and during his reign the double-headed eagle was adopted, which was to remain part of the insignia of Russian rulers until 1917. This gave a further Byzantine colouring to Russian monarchy and Russian history, which became still more unlike that of western Europe. By 1500 western Europeans already recognized a distinctive kind of monarchy in Russia; Basil, Ivan’s successor, was acknowledged to have a despotic power over his subjects greater than that of any other Christian rulers over theirs. Hindsight makes much of Europe’s future seem already discernible by 1500. A great process of definition and realization had been going on for centuries. Europe’s land limits were now filled up; in the East further advance was blocked by the consolidation of Christian Russia, in the Balkans by the Ottoman empire of Islam. The first, crusading, wave of overseas expansion was virtually spent by about 1250. With the onset of the Ottoman threat in the fifteenth century, Europe was again forced on the defensive in the eastern Mediterranean and Balkans. Those unhappy states with exposed territories in the East, such as Venice, had to look after them as best they could. Meanwhile, others were taking a new look at their oceanic horizons. A new phase of western Europe’s relations with the rest of the world was about to open.

In 1400 it had still seemed sensible to see Jerusalem as the centre of the

world. Though the Vikings had crossed the Atlantic, men could still think of a world which, though spherical, was made up of three continents, Europe, Asia and Africa, around the shores of one land-locked sea, the Mediterranean. A huge revolution lay just ahead, which for ever swept away such views, and the route to it lay across the oceans because elsewhere advance was blocked. Europe’s first direct contacts with the East had been on land rather than on water. The caravan routes of central Asia were their main channel and brought goods west to be shipped from Black Sea or Levant ports. Elsewhere, ships rarely ventured far south of Morocco until the fifteenth century. Then, a mounting wave of maritime enterprise becomes noticeable. With it, the age of true world history was beginning.

One explanation of it was the acquisition of new tools and skills. Different ships and new techniques of long-range navigation were needed for oceanic sailing and they became available from the fourteenth century onwards, thus making possible the great effort of exploration which has led to the fifteenth century being called ‘the Age of Reconnaissance’. In ship design there were two crucial changes. One was specific, the adoption of the stern-post rudder; though we do not know exactly when this happened, some ships had it by 1300. The other was a more gradual and complex process of improving rigging. This went with a growth in the size of ships. A more complex maritime trade no doubt spurred such developments. By 1500, the tubby medieval ‘cog’ of northern Europe, square-rigged with a single sail and mast, had developed into a ship carrying up to three masts, with mixed sails. The main-mast still carried square-rigging, but more than one sail; the mizzen-mast had a big lateen sail borrowed from the Mediterranean tradition; a fore-mast might carry more square-rigged sails, but also newly invented fore-and-aft jib sails attached to a bowsprit. Together with the lateen sail aft, these head-sails made vessels much more manoeuvrable; they could be sailed much closer to the wind.