The New Penguin History of the World (120 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

In the early eighteenth century there thus existed a Dutch supremacy in

the Indian Ocean and Indonesia, and an important Dutch interest in the China seas. To a remarkable degree this reproduced the earlier Portuguese pattern, although there survived Portuguese stations such as Goa and Macao. The heart of Dutch power was the Malacca Strait, from which it radiated through Malaysia and Indonesia, to Formosa and the trading links with China and Japan, and down to the south-east to the crucial Moluccas. This area was by now enjoying an internal trade so considerable that it was beginning to be self-financing, with bullion from Japan and China providing its flow of currency rather than bullion from Europe as in the early days. Further west, the Dutch were also established at Calicut, in Ceylon and at the Cape of Good Hope, and had set up factories in Persia. Although Batavia was a big town and the Dutch were running plantations to grow the goods they needed, this was still a littoral or insular commercial empire, not one of internal dominion over the mainland. In the last resort it rested on naval power and it was to succumb, though not to disappear, as Dutch naval power was surpassed.

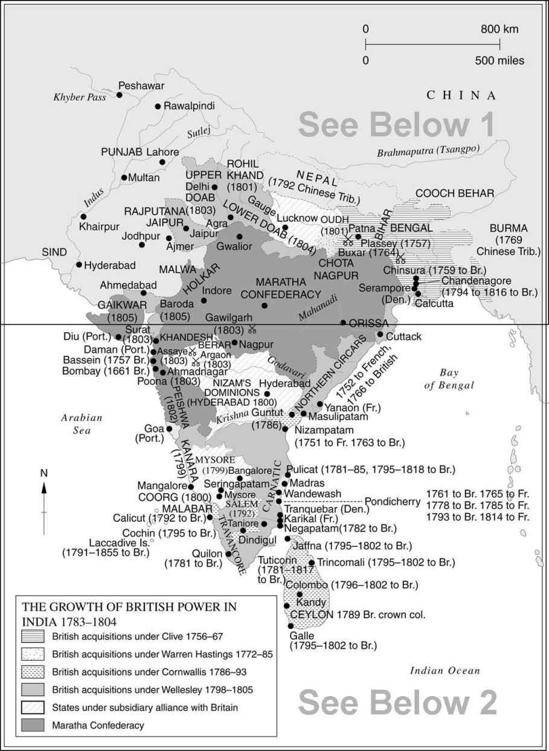

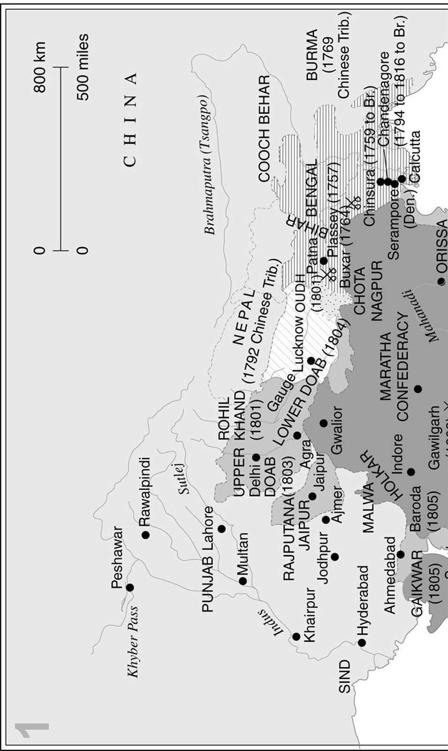

This was clearly beginning to happen in the last decades of the seventeenth century. The unlikely challenger for Indian Ocean supremacy was England. At an early date the English had sought to enter the spice trade. There had been an East Indian Company under James I, but its factors had got bloody noses for their pains, both when they tried to cooperate with the Dutch and when they fought them. The upshot of this was that by 1700 the English had in effect drawn a line under their accounts east of the Malacca Strait. Like the Dutch in 1580, they were faced with a need to change course and did so. The upshot was the most momentous event in British history between the Protestant Reformation and the onset of industrialization – the acquisition of supremacy in India.

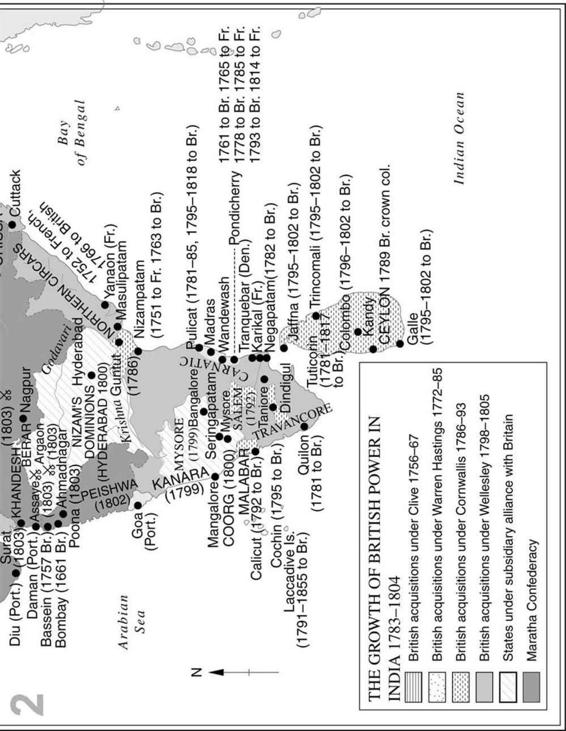

In India the main rivals of the English were not the Dutch or Portuguese, but the French. What was at stake did not emerge for a long time. The rise of British power in India was very gradual. After the establishment of Fort St George at Madras and the acquisition of Bombay from the Portuguese as a part of the dowry of Charles II’s queen, there was no further English penetration of India until the end of the century. From their early footholds (Bombay was the only territory they held in full sovereignty) Englishmen conducted a trade in coffee and textiles less glamorous than the Dutch spice trade, but one which grew in value and importance. It also changed their national habits, and therefore society, as the establishment of coffee-houses in London showed. Soon, ships began to be sent from India to China for tea; by 1700 Englishmen had acquired a new national beverage and a poet would soon commemorate what he termed ‘cups that cheer but not inebriate’.

As a defeat of the East India Company’s forces in 1689 showed, military

domination in India was unlikely to prove easy. Moreover, it was not necessary to prosperity. The Company therefore did not wish to fight if it could avoid it. Though at the end of the century a momentous acquisition was made when the Company was allowed to occupy Fort William, which it had built at Calcutta, the directors in 1700 rejected the idea of acquiring fresh territory or planting colonies in India as quite unrealistic. Yet all preconceptions were to be changed by the collapse of the Moghul empire after the death of Aurungzebe in 1707. The consequences emerged slowly, but their total effect was that India dissolved into a collection of autonomous states with no paramount power.

The Moghul empire had already before 1707 been troubled by the Marathas. The centrifugal tendencies of the empire had always favoured the

nawabs

, or provincial governors, too, and power was divided between them and the Marathas with increasing obviousness. The Sikhs provided a third focus of power. Originally appearing as a Hindu sect in the sixteenth century, they had turned against the Moghuls but had also drawn away from orthodox Hinduism to become virtually a third religion with it and Islam. The Sikhs formed a military brotherhood, had no castes, and were well able to look after their own interests in a period of disunion. Eventually a Sikh empire appeared in north-west India which was to endure until 1849. Meanwhile, there were signs in the eighteenth century of an increasing polarity between Hindu and Muslim. The Hindus withdrew more into their own communities, hardening the ritual practices which publicly distinguished them. The Muslims reciprocated. On this growing dislocation, presided over by a Moghul military and civil administration which was conservative and unprogressive, there fell also a Persian invasion in the 1730s and consequent losses of territory.

There were great temptations to foreign intervention in this situation. In retrospect it seems remarkable that both British and French took so long to take advantage; even in the 1740s the British East India Company was still less wealthy and powerful than the Dutch. This delay is a testimony to the importance still attached to trade as their main purpose. When they did begin to intervene, largely moved by hostility to the French and fear of what they might do, the British had several important advantages. The possession of a station at Calcutta placed them at the door to that part of India which was potentially the richest prize – Bengal and the lower Ganges valley. They had assured sea communications with Europe, thanks to British naval power, and ministers listened to the East India merchants in London as they did not listen to French merchants at Versailles. The French were the most dangerous potential competitors but their government was always likely to be distracted by its European continental commitments. Finally, the British lacked missionary zeal; this was true in the narrow sense that Protestant interest in missions in Asia quickened later than Catholic, and also, more generally, in that they had no wish to interfere with native custom or institution but only – somewhat like the Moghuls – to provide a neutral structure of power within which Indians could carry on their lives as they wished, while the commerce from which the Company profited prospered in peace.

The way into an imperial future led through Indian politics. Support for rival Indian princes was the first, indirect, form of conflict between French and British. In 1744 this led for the first time to armed struggle between British and French forces in the Carnatic, the south-eastern coastal region. India had been irresistibly sucked into the worldwide conflict between British and French power. The Seven Years’ War (1756–63) was decisive. Before its outbreak, there had in fact been no remission of fighting in India, even while France and Great Britain were officially at peace after 1748. The French cause had prospered under a brilliant French governor in the Carnatic, Dupleix, who caused great alarm to the British by his extension of French power among native princes by force and diplomacy. But he was recalled to France and the French Indian company was not to enjoy the wholehearted support of the metropolitan government which it needed to emerge as the new paramount power. When war broke out again, in 1756, the

nawab

of Bengal attacked and captured Calcutta. His treatment of his English prisoners, many of whom were suffocated in the soon legendary ‘Black Hole’, gave additional offence. The East India Company’s army, commanded by its employee, Robert Clive, retook the city from him, seized the French station at Chandernagore and then on 22 June 1757 won a battle over the

nawab

’s much larger armies at Plassey, about a hundred miles up the Hooghly from Calcutta.

It was not very bloody (the

nawab

’s army was suborned) but it was one of the decisive battles of world history. It opened to the British the road to the control of Bengal and its revenues. On these was based the destruction of French power in the Carnatic; that opened the way to further acquisitions which led, inexorably, to a future British monopoly of India. Nobody planned this. The British government, it is true, had begun to grasp what was immediately at stake in terms of a threat to trade and sent out a battalion of regular troops to help the Company; the gesture is doubly revealing, both because it recognized that a national interest was involved, but also because of the tiny scale of this military effort. A very small number of European troops with European field artillery could be decisive. The fate of India turned on the Company’s handful of European and European-trained soldiers, and on the diplomatic skills and acumen of its agents on the spot. Upon this narrow base and the need for government in a disintegrating India was to be built the British Raj.

In 1764 the East India Company became the formal ruler of Bengal. This had by no means been the intention of the Company’s directors, who sought not to govern but to trade. However, if Bengal could pay for its own government, then the burden could be undertaken. There were now only a few scattered French bases; the peace of 1763 left five trading posts

on condition that they were not fortified. In 1769 the French Compagnie des Indes was dissolved. Soon after, the British took Ceylon from the Dutch and the stage was cleared for a unique example of imperialism.

The road would be a long one and was for a long time followed reluctantly, but the East India Company was gradually drawn on by its revenue problems and by the disorder of native administrations in contiguous territories to extend its own governmental aegis. The obscuring of the company’s primary commercial role was not good for business. It also gave its employees even greater opportunities to feather their own nests. This drew the interest of British politicians, who first cut into the powers of the directors of the company and then brought it firmly under the control of the Crown, setting up in 1784 a system of ‘dual control’ in India which was to last until 1858. In the same Act were provisions against further interference in native affairs; the British government hoped as fervently as the Company to avoid being dragged any further into the role of imperial power in India. But this was what happened in the next half-century, as many more acquisitions followed. The road was open which was to lead eventually to the enlightened despotism of the nineteenth-century Raj. India was quite unlike any other dependency so far acquired by a European state in that hundreds of millions of subjects were to be added to the empire without any conversion or assimilation of them being envisaged except by a few visionaries and at a very late date. The character of the British imperial structure would be profoundly transformed by this, and so, eventually, would be British strategy, diplomacy, external trade patterns and even outlook.

Except in India and Dutch Indonesia, no territorial acquisitions in the East in these centuries could be compared to the vast seizures of lands by Europeans in the Americas. Columbus’s landing had been followed by a fairly rapid and complete exploration of the major ‘West Indian’ islands. It was soon clear that the conquest of American lands was attractively easy by comparison with the struggles to win north Africa from the Moors, which had immediately followed the fall of Granada and the completion of the Reconquest on the Spanish mainland. Settlement rapidly made headway, particularly in Hispaniola and Cuba. The cornerstone of the first cathedral in the Americas was laid in 1523; the Spaniards, as their city-building was intended to show, had come to stay. Their first university (in the same city, Santo Domingo) was founded in 1538 and the first printing-press was set up in Mexico in the following year.