The New Penguin History of the World (160 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

A new cultural self-respect and a growing sense of grievance over rewards and slights were the background to the formation of the Indian National Congress. The immediate prelude was a flurry of excitement over the failure of the government proposals – because of the outcry of European residents – to equalize the treatment of Indians and Europeans in the courts. Disappointment caused an Englishman, a former civil servant, to take the steps which led to the first conference of the Indian National Congress in Bombay in December 1885. Vice-regal initiatives, too, had played a part in this, and Europeans were long to be prominent in the administration of Congress. And they would they patronize it for even longer with protection and advice in London. It was an appropriate symbol of the complexity

of the European impact on India that some Indian delegates attended in European dress, improbably attired in morning-suits and top-hats of comical unsuitability to the climate of their country, but the formal attire of its rulers.

Congress was soon committed by its declaration of principles to national unity and regeneration: as in Japan already and China and many other countries later, this was the classical product of the impact of European ideas. But it did not at first aspire to self-government. Congress sought, rather, to provide a means of communicating Indian views to the viceroy and proclaimed its ‘unswerving loyalty’ to the British Crown. Only after twenty years, in which much more extreme nationalist views had won adherents among Hindus, did it begin to discuss the possibility of independence. During this time its attitude had been soured and stiffened by the vilification it received from British residents who declared it unrepresentative, and the unresponsiveness of an administration which endorsed this view and preferred to work through more traditional and conservative social forces. Extremists became more insistent. In 1904 came the inspiring victories of Japan over Russia. The issue for a clash was provided in 1905 by the partition of Bengal.

Its purpose was twofold: it was administratively convenient and it would undermine nationalism in Bengal by producing a West Bengal where there was a Hindu majority, and an East Bengal with a Muslim majority. This detonated a mass of explosive situations that had long been accumulating. Immediately, there was a struggle for power in Congress. At first a split was avoided by agreement on the aim of

swaraj

, which in practice might mean independent self-government such as that enjoyed by the white dominions: their example was suggestive. The extremists were heartened by anti-partition riots. A new weapon was deployed against the British, a boycott of goods, which, it was hoped, might be extended to other forms of passive resistance such as non-payment of taxes and the refusal of soldiers to obey orders. By 1908 the extremists were excluded from Congress. By this time, a second consequence was apparent: extremism was producing terrorism. Again, foreign models were important. Russian revolutionary terrorism now joined the works of Mazzini and the biography of Garibaldi, the guerrilla leader-hero of Italian independence, as formative influences on an emerging India. The extremists argued that political murder was not ordinary murder. Assassination and bombing were met with special repressive measures.

The third consequence of partition was perhaps the most momentous. It brought out into the open the division of Muslim and Hindu. For reasons which went back to the percolation of Muslim India before the Mutiny

by an Islamic reform movement, the Arabian Wahhabi sect, Indian Muslims had for a century felt themselves more and more distinct from Hindus. Distrusted by the British because of attempts to revivify the Moghul empire in 1857, they had little success in winning posts in government or on the judicial bench. Hindus had responded more eagerly than Muslims to the educational opportunities offered by the Raj; they were of more commercial weight and had more influence on government. But Muslims, too, had found their British helpers, who had established a new, Islamic college, providing the English education they needed to compete with Hindus, and had helped to set up Muslim political organizations. Some English civil servants began to grasp the potential for balancing Hindu pressure which this could give the Raj. Intensification of Hindu ritual practice, such as a cow protection movement, was not likely to do anything but increase the separation of the two communities.

Nevertheless, it was only in 1905 that the split became, as it remained, one of the fundamentals of the subcontinent’s politics. The anti-partitionists campaigned with a strident display of Hindu symbols and slogans. The British governor of eastern Bengal favoured Muslims against Hindus and strove to give them a vested interest in the new province. He was dismissed, but his inoculation had taken: Bengal Muslims deplored his removal. An Anglo-Muslim

entente

seemed in the making. This further inflamed Hindu terrorists. To make things worse, all this was taking place during five years (from 1906 to 1910) in which prices rose faster than at any time since the Mutiny.

An important set of political reforms conceded in 1909 did not do more than change somewhat the forms with which to operate the political forces which were henceforth to dominate the history of India until the Raj came to an end nearly forty years later. Indians were for the first time appointed to the council which advised the British minister responsible for India and, more important, further elected places were provided for Indians in the legislative councils. But the elections were to be made by electorates which had a communal basis; the division of Hindu and Muslim India, that is to say, was institutionalized.

In 1911, for the first and only time, a reigning British monarch visited India. A great imperial durbar was held at Delhi, the old centre of Moghul rule, to which the capital of British India was now transferred from Calcutta. The princes of India came to do homage; Congress did not question its duty to the throne. The accession to the throne of George V that year had been marked by the conferring of real and symbolic benefits, of which the most notable and politically significant was the reuniting of Bengal. If there was a moment at which the Raj was at its apogee, this was it.

Yet India was far from settled. Terrorism and seditious crime continued. The policy of favouring the Muslims had made Hindus more resentful while Muslims now felt that the government had gone back on its understandings with them in withdrawing the partition of Bengal. They feared the resumption of a Hindu ascendancy in the province. Hindus, on the other hand, took the concession as evidence that resistance had paid and began to press for the abolition of the communal electoral arrangements which the Muslims prized. The British had therefore done much to alienate Muslim support when a further strain appeared. The Indian Muslim élites, which had favoured cooperation with the British, were increasingly under pressure from more middle-class Muslims susceptible to the violent appeal of a pan-Islamic movement. The pan-Islamists could point to the fact that the British had let the Muslims down in Bengal, but also noted that in Tripoli (which the Italians attacked in 1911) and the Balkans in 1912 and 1913, Christian powers were attacking Turkey, the seat of the Caliphate, the institutional embodiment of the spiritual leadership of Islam, and Great Britain was, indisputably, a Christian power. The intense susceptibilities of lower-class Indian Muslims were excited to the point at which even the involvement of a mosque in the replanning of a street could be presented as a part of a deliberate plot to harry Islam. When in 1914 Turkey decided to go to war with Great Britain, though the Muslim League remained loyal, some Indian Muslims accepted the logical consequence of the Caliphate’s supremacy, and began to prepare revolution against the Raj. They were few. What was more important for the future was that by that year not two but three forces were making the running in Indian politics: the British, Hindus and Muslims. Here was the origin of the future partition of the only complete political unity the subcontinent had ever known and, like that unity, it was as much the result of the play of non-Indian as of Indian forces.

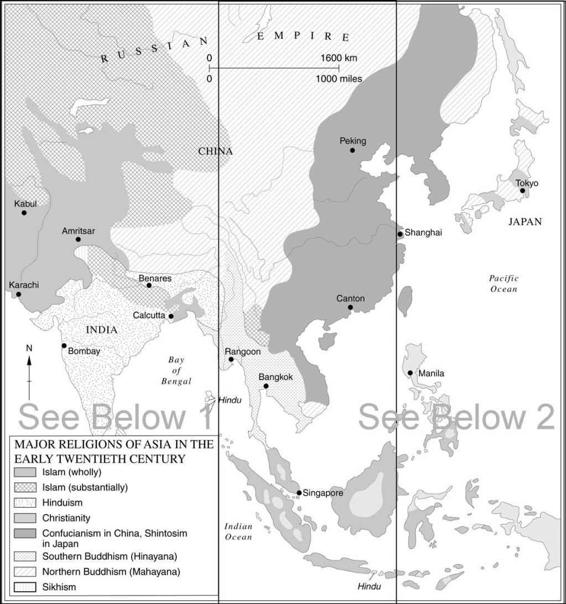

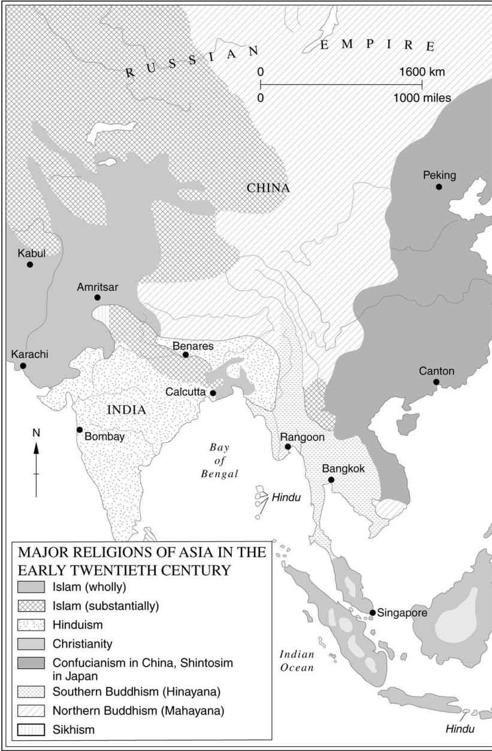

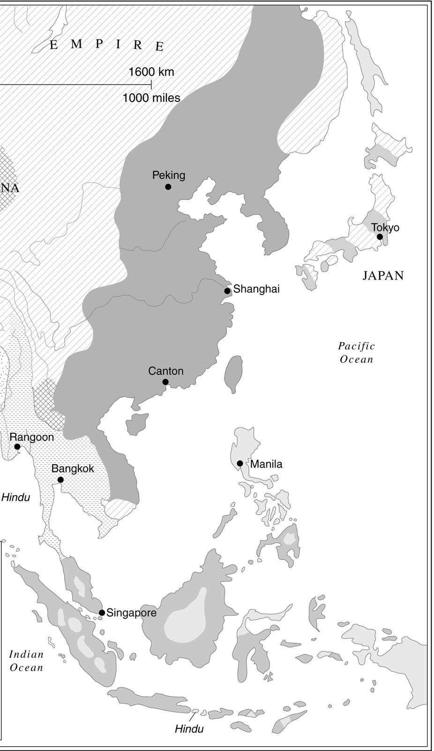

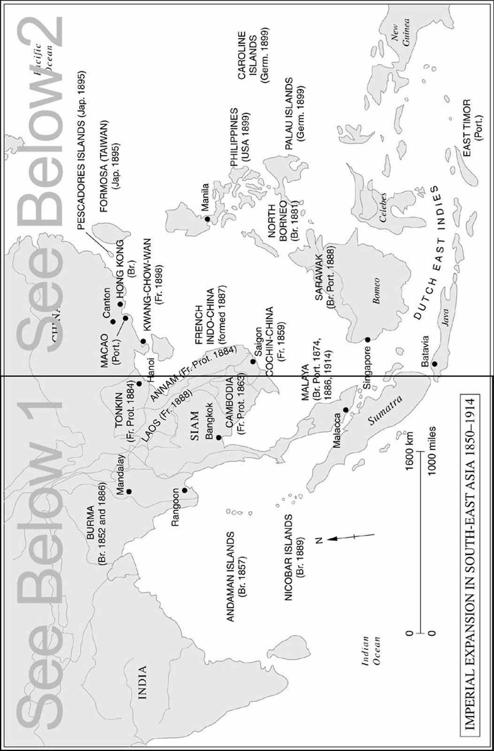

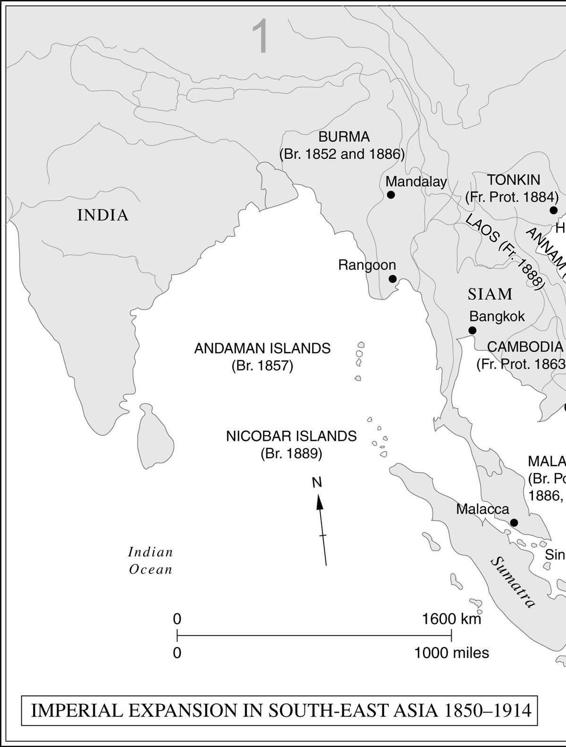

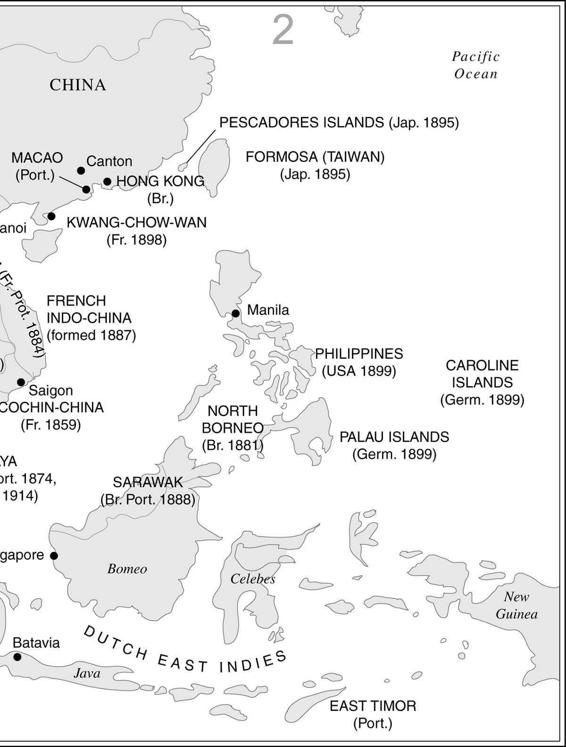

India was the largest single mass of non-European population and territory under European rule in Asia, but to the south-east and in Indonesia, both part of the Indian cultural sphere, lay further imperial possessions. Few generalizations are possible about so huge an area and so many peoples and religions. One negative fact was observable: in no other European possession in Asia was there such transformation before 1914 as in India, though in all of them modernization had begun the corrosion of local tradition. The forces which produced this were those which have already been noted at work elsewhere: European aggression, the example of Japan,

and the diffusion of European culture. But the first and last of these forces operated in the region for a shorter time before 1914 than in China and India. In 1880 most of mainland South-East Asia was still ruled by native princes who were independent rulers, even if they had to make concessions in ‘unequal treaties’ to European power. In the following decade this was rapidly changed by the British annexation of Burma and continuing French expansion in Indo-China. The sultans of Malaya acquired British residents at their courts, who directed policy through the native administration, while the ‘Straits settlements’ were ruled directly as a colony. By 1900 only Siam was left as an independent kingdom in the region, those of Indo-China having succumbed to French imperialism.