The New Penguin History of the World (178 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Like Stalin’s Russia, the Nazi regime rested in large measure on terror used mercilessly against its enemies. It was soon unleashed against the Jews and an astonished Europe found itself witnessing revivals in one of its most advanced societies of the pogroms of medieval Europe or Tsarist Russia. This was indeed so amazing that many people outside Germany found it difficult to believe that it was happening. Confusion over the nature of the regime made it even more difficult to deal with. Some saw Hitler simply as a nationalist leader bent, like an Ataturk, upon the regeneration of his country and the assertion of its rightful claims. Others saw him as a crusader against Bolshevism. Even when people only thought he might be a useful barrier against it, that increased the likelihood that men of the Left would see him as a tool of capitalism. But no simple formula will contain Hitler or his aims – and there is still great disagreement about what these were – and probably a reasonable approximation to the truth is simply to recognize that he expressed the resentments and exasperations of German society in their most negative and destructive forms and embodied them to a monstrous degree. When his personality was given scope by economic disaster, political cynicism and a favourable arrangement of international forces, he could release these negative qualities at the expense of all Europeans in the long run, his own countrymen included.

The path by which Germany came to be at war again in 1939 is complicated. Argument is still possible about when, if ever, there was a chance of avoiding the final outcome. One important moment, clearly, was when Mussolini, formerly wary of German ambitions in central Europe, became Hitler’s ally. After he had been alienated by British and French policy over his Ethiopian adventure, a civil war broke out in Spain when a group of generals mutinied against the left-wing republic. Hitler and Mussolini both sent contingents to support the man who emerged there as the rebel leader, General Franco. This, more than any other single fact, gave an ideological colour to Europe’s divisions. Hitler, Mussolini and Franco were all now identified as ‘fascist’ and Russian foreign policy began to coordinate support for Spain within western countries by letting local communists abandon their attacks on other left-wing parties and encouraging ‘Popular Fronts’. Thus Spain came to be seen as a conflict between Right and Left in its purest form; this was a distortion, but it encouraged people to think of Europe as divided into two camps.

British and French governments were by this time well aware of the difficulties of dealing with Germany. Hitler had already in 1935 announced that her rearmament (forbidden at Versailles) had begun. Until their own rearmament was completed, they remained very weak. The first consequence of this was shown to the world when German troops re-entered the ‘demilitarized’ zone of the Rhineland from which they had been excluded by the Treaty of Versailles. No attempt was made to resist this move. After the civil war in Spain had thrown opinion in Great Britain and France into further disarray, Hitler then seized Austria. The terms of Versailles, which forbade the fusion of Germany and Austria, seemed hard to uphold; to the French and British electorates this could be presented as a matter of legitimately aggrieved nationalism. The Austrian republic had also long had internal troubles. The

Anschluss

(as union with Germany was called) took place in March 1938. In the autumn came the next German aggression, the seizure of part of Czechoslovakia. Again, this was justified by the specious claims of self-determination; the areas involved were so important that their loss crippled the prospect of future Czechoslovak self-defence, but they were areas with many German inhabitants. Memel would follow, on the same grounds, the next year. Hitler was gradually fulfilling the old dream which had been lost when Prussia beat Austria – the dream of a united Great Germany, defined as all lands of those of German blood.

The dismemberment of Czechoslovakia had been something of a turning-point. It was achieved by a series of agreements at Munich in September 1938 in which Great Britain and Germany took the main parts. This was the last great initiative of British foreign policy to try to satisfy Hitler. The British prime minister was still too unsure of rearmament to resist, but hoped also that the transference of the last substantial group of Germans from alien rule to that of their homeland might deprive Hitler of the motive for further revision of Versailles – a settlement which was now somewhat tattered in any case.

He was wrong, because Hitler went on to inaugurate a programme of expansion into Slav lands. The first step was the absorption of what was left of Czechoslovakia, in March 1939. This brought forward the question of the Polish settlement of 1919. Hitler resented the ‘Polish Corridor’, which separated East Prussia from Germany and contained Danzig, an old German city given an international status in 1919. At this point the British government, though hesitatingly, changed tack and offered a guarantee to Poland, Romania, Greece and Turkey against aggression. It also began a wary negotiation with Russia.

Russian policy remains hard to interpret. It seems that Stalin kept the Spanish Civil War going with support to the republic as long as it seemed likely to tie up German attention, but then looked for other ways of buying time against the attack from the west which he always feared. To him, it seemed likely that a German attack on Russia might be encouraged by

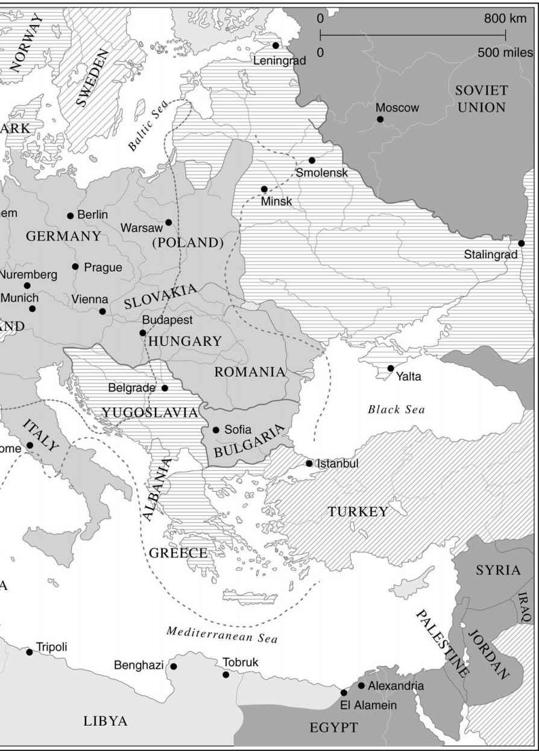

Great Britain and France, who would see with relief the danger they had so long faced turning against the workers’ state. No doubt they would have done. There was little possibility of working with the British or French to oppose Hitler, however, even if they were willing to do so, because no Russian army could reach Germany except through Poland – and this the Poles would never permit. Accordingly, as a Russian diplomat remarked to a French colleague on hearing of the Munich decisions, there was now nothing for it but a fourth partition of Poland. This was arranged in the summer of 1939. After their bitter respective diatribes against Bolshevik–Slav barbarism and fascist–capitalist exploitation, Germany and Russia made an agreement in August which provided for the division of Poland between them; authoritarian states enjoy great flexibility in the conduct of diplomacy. Armed with this, Hitler went on to attack Poland. He thus began the Second World War on 1 September 1939. Two days later the British and French honoured their guarantee to Poland and declared war on Germany.

Their governments were not very keen on doing so, for it was obvious that they could not help Poland. That unhappy nation disappeared once more, divided by Russian and German forces about a month after the outbreak of war. But not to have intervened would have meant acquiescing in the German domination of Europe, for no other nation would then have thought British or French support worth having. So, uneasily and without the excitement of 1914, the only two constitutional great powers of Europe found themselves facing a totalitarian regime. Neither their peoples nor governments had much enthusiasm for this role, and the decline of liberal and democratic forces since 1918 put them in a position much inferior to that of the Allies of 1914, but exasperation with Hitler’s long series of aggressions and broken promises made it hard to see what sort of peace could be made which would reassure them. The basic cause of the war was, as in 1914, German nationalism. But whereas then Germany had gone to war because it felt threatened, now Great Britain and France were responding to the danger presented by Germany’s expansion.

They

felt threatened this time.

To the surprise of many observers, and the relief of some, the first six months of the war were almost uneventful once the short Polish campaign was over. It was quickly plain that mechanized forces and airpower were to play a much more important part than between 1914 and 1918. The memory of the slaughter of the Somme and Verdun was too vivid for the British and French to plan anything but an economic offensive; the weapon of blockade, they hoped, would be effective. Hitler was unwilling to disturb them, because he was anxious to make peace. This deadlock was only

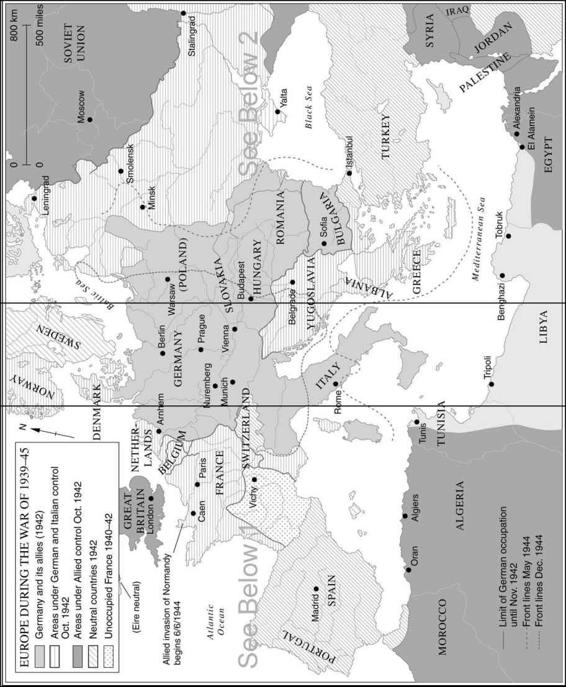

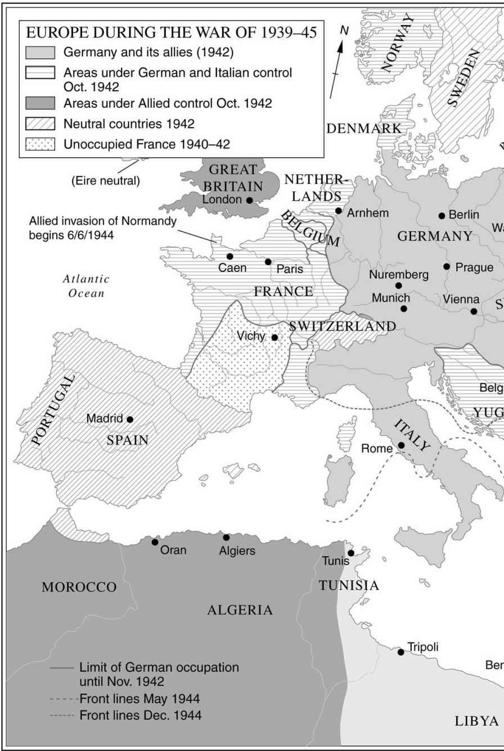

broken when the British sought to intensify the blockade in Scandinavian waters. This coincided, remarkably, with a German offensive to secure ore supplies, which conquered Norway and Denmark. Its launching on 9 April 1940 opened an astonishing period of fighting. Only a month later there began a brilliant German invasion, first of the Low Countries and then of France. A powerful armoured attack through the Ardennes opened the way to the division of the Allied armies and the capture of Paris. On 22 June France signed an armistice with the Germans. By the end of the month, the whole European coast from the Pyrenees to the North Cape was in German hands. Italy had joined in on the German side ten days before the French surrender. A new French government at Vichy broke off relations with Great Britain after the British had seized or destroyed French warships they feared might fall into German hands. The Third Republic effectively came to an end with the installation of a French marshal, a hero of the First World War, as head of state. With no ally left on the continent, Great Britain faced a worse strategic situation by far than that in which she had struggled against Napoleon.

This was a huge change in the nature of the war, but Great Britain was not quite alone. There were the Dominions, all of which had entered the war on her side, and a number of governments in exile from the overrun continent. Some of these commanded forces of their own and Norwegians, Danes, Dutchmen, Belgians, Czechs and Poles were to fight gallantly, often with decisive effect, in the years ahead. The most important exiled contingents were those of the French, but at this stage they represented a faction within France, not its legal government. A general who had left France before the armistice and was condemned to death

in absentia

was their leader: Charles de Gaulle. He was recognized by the British only as ‘leader of the Free French’ but saw himself as constitutional legatee of the Third Republic and the custodian of France’s interests and honour. He soon began to show an independence which was in the end to make him the greatest servant of his country since Clemenceau.

De Gaulle was immediately important to the British because of uncertainties about what might happen to parts of the French empire where he hoped to find sympathizers who wished to join him to continue the fight. This was one way in which the war was now extended geographically. This was also a consequence of Italy’s entry into the war, since her African possessions and the Mediterranean sea-lanes now became operational areas. Finally, the availability of Atlantic and Scandinavian ports to the Germans meant that what was later called the ‘Battle of the Atlantic’, the struggle by submarine, surface and air attack to sever or wear down British sea communications was now bound to become much fiercer.

Immediately, the British Isles faced direct attack. The hour had already found the man to brace the nation against such a challenge. Winston Churchill, after a long and chequered political career, had become Prime Minister when the Norwegian campaign collapsed, because no other man commanded support in all parties in the House of Commons. To the coalition government which he immediately formed he gave vigorous leadership, something hitherto felt to be lacking. More important than this, he called forth in his people, whom he could address by radio, qualities they had forgotten they possessed. It was soon clear that only defeat after direct assault was going to get the British out of the war.