The New Penguin History of the World (47 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

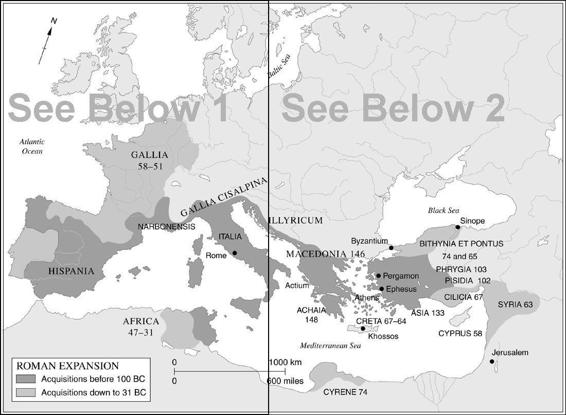

One former supporter and protégé of Sulla was a young man whose name has passed into English as Pompey. Sulla had advanced his career by giving him posts normally held only by consuls and in 70

BC

he was elected to that office, too. He left for the east three years later to eliminate piracy from the Mediterranean and went on to conquer huge Asian territories in the wars against Pontus. Pompey’s youth, success and outstanding ability began to make him feared as a potential dictator. But the interplay of Roman politics was complicated. As the years passed, disorder increased in the capital and corruption in ruling circles. Fears of dictatorship were intensified, but the fears were those of one oligarchic faction among several and it was less and less clear where the danger lay. Moreover one danger went long disregarded before people awoke to it.

In 59

BC

another aristocrat, the nephew of Marius’s wife, had been elected consul. This was the young Julius Caesar. For a time he had cooperated with Pompey. The consulship led him to the command of the army of Gaul and a succession of brilliant campaigns in the next seven years, ending in its complete conquest. Though he watched politics closely, these years kept Caesar away from Rome where gangsterism, corruption and murder disfigured public life and discredited the Senate. After them he was enormously rich and had a loyal, superbly experienced and confident army looking to him for the leadership, which would give them pay, promotion and victory in the future. He was also a cool, patient and ruthless man. There is a story of him joking and playing at dice with some pirates who captured him. One of his jokes was that he would crucify them when he was freed. The pirates laughed, but crucify them he did.

Some senators suddenly became alarmed when this formidable man wished to remain in Gaul in command of his army and the province, although its conquest was complete, retaining command until the consular election. His opponents strove to get him recalled to face charges about illegalities during his consulship. Caesar then took the step which, though neither he nor anyone else knew it, was the beginning of the end of the republic. He led his army across the Rubicon, the boundary of his province, beginning a march which brought him in the end to Rome. This was in January 49

BC

. It was an act of treason, though he claimed to be defending the republic against its enemies.

In its extremity the Senate called Pompey to defend the republic. Without forces in Italy, Pompey withdrew across the Adriatic to raise an army. The consuls and most of the Senate went with him. Civil war was now inevitable.

Caesar marched quickly to Spain to defeat seven legions there which were loyal to Pompey; they were then mildly treated in order to win over as many of the soldiers as possible. Ruthless and even cruel though he could be, mildness to his political opponents was politic and prudent; he did not propose to imitate Sulla, said Caesar. Then he went after Pompey, chasing him to Egypt, where he was murdered. Caesar stayed long enough to dabble in an Egyptian civil war and became, almost incidentally, the lover of the legendary Cleopatra. Then he went back to Rome, to embark almost at once for Africa and defeat a Roman army there which opposed him. Finally, he returned again to Spain and destroyed a force raised by Pompey’s sons. This was in 45

BC

, four years after the crossing of the Rubicon.

Brilliance like this was not just a matter of winning battles. Brief though Caesar’s recent visits to Rome had been, he had organized his political support carefully and packed the Senate with his men. The victories brought him great honours and real power. He was voted dictator for life and became in effect a monarch in all but name. His power he used without much regard for the susceptibilities of politicians and without showing an imaginativeness which suggests his rule would have been successful in the long term, although he imposed order in the Roman streets, and undertook steps to end the power of the money-lenders in politics. To one reform in particular the future of Europe was to owe much – the introduction of the Julian calendar. Like much else we think of as Roman, it came from Hellenistic Alexandria, where an astronomer suggested to Caesar that the year of 365 days, with an extra day each fourth year, would make it possible to emerge from the complexities of the traditional Roman calendar. The new calendar began on 1 January 45

BC

.

Fifteen months later Caesar was dead, struck down in the Senate on 15 March 44

BC

at the height of his success. His assassins’ motives were complex. The timing was undoubtedly affected by the knowledge that he planned a great eastern campaign against the Parthians. Were he to join his army, it might be to return again in triumph, more unassailable than ever. There had been talk of a kingship; a Hellenistic despotism was envisaged by some. The complicated motives of his enemies were given respectability by the distaste some felt for the flagrant affront to republican tradition in the

de facto

despotism of one man. Minor acts of disrespect for the constitution antagonized others and in the end his assassins were a mixed bag of disappointed soldiers, interested oligarchs and offended conservatives.

His murderers had no answer to the problems which Caesar had not had the time, and their predecessors had so conspicuously failed, to solve.

Nor could they protect themselves for long. The republic was pronounced restored, but Caesar’s acts were confirmed. There was a revulsion of feeling against the conspirators who soon had to flee the city. Within two years they were dead and Julius Caesar was proclaimed a god. The republic was moribund, too. Damaged fatally long before the crossing of the Rubicon, the heart had gone out of its constitution whatever attempts were made to restore it. Yet its myths, its ideology and forms lived on in a Romanized Italy. Romans could not bring themselves to turn their backs on the institutional heritage and admit that they had done with it. When eventually they did, they had already ceased in all but name and aspiration to resemble the Romans of the republic.

6

The Roman Achievement

If the Greek contribution to civilization was essentially mental and spiritual, that of Rome was structural and practical; its essence was the empire itself. Though no man is an empire, not even the great Alexander, its nature and government were to an astonishing degree the creation of one man of outstanding ability, Julius Caesar’s great-nephew and adopted heir, Octavian. Later he was celebrated as Caesar Augustus. An age has been named after him; his name gave an adjective to posterity. Sometimes one has the feeling that he invented almost everything that characterized imperial Rome, from the new Praetorian Guard, which was the first military force stationed permanently in the capital, to the taxation of bachelors. One reason for this impression (though only one) is that he was a master of public relations; significantly, more representations of him than of any other Roman emperor have come down to us.

Though a Caesar, Octavian came of a junior branch. From Julius he inherited at the age of eighteen aristocratic connections, great wealth and military support. For a time he cooperated with one of Caesar’s henchmen, Mark Antony, in a ferocious series of proscriptions to destroy the party which had murdered the great dictator. Mark Antony’s departure to win victories in the east, failure to do so and injudicious marriage to Cleopatra, Julius Caesar’s sometime mistress, gave Octavian further opportunities. He fought in the name of the republic against a threat that Antony might make a proconsular return, bringing oriental monarchy in his baggage-train. The victory of Actium (31

BC

) was followed by the legendary suicides of Antony and Cleopatra; the kingdom of the Ptolemies came to an end and Egypt too was annexed as a province of Rome.

This was the end of civil war. Octavian returned to become consul. He had every card in his hand and judiciously refrained from playing them, leaving it to his opponents to recognize his strength. In 27

BC

he carried out what he called a republican restoration with the support of a Senate whose republican membership, purged and weakened by civil war and proscription, he reconciled to his real primacy by his careful preservation

of forms. He re-established the reality of his great-uncle’s power behind a façade of republican piety. He was

imperator

only by virtue of his command of the troops of the frontier provinces – but that was where the bulk of the legions were. As old soldiers of his and his great-uncle’s armies returned to retirement, they were duly settled on smallholdings and were appropriately grateful. His consulship was prolonged from year to year and in 27

BC

he was given the honorific title of Augustus, the name by which he is remembered. At Rome, though, he was formally and usually called by his family name, or was identified as

princeps

, first citizen. As the years passed Augustus’s power still grew. The Senate accorded him a right of interference in those provinces which it formally ruled (that is, those where there was no need to keep a garrison army). He was voted the tribunician power. His special status was enhanced and formalized by a new recognition of his state or

dignitas

, as the Romans called it; he sat between the two consuls after his resignation from that office in 23

BC

and his business was given precedence in the agenda of the Senate. Finally, in 12

BC

he became

pontifex maximus

, the head of the official cult, as his great-uncle had been. The forms of the republic with their popular elections and senatorial elections were maintained, but Augustus said who should be elected.

The political reality masked by this supremacy was the rise to domination within the ruling class of men who owed their position to the Caesars. But the new élites were not to be allowed to behave like the old. The Augustan benevolent despotism regularized the provincial administration and army by putting them into obedient and salaried hands. The conscious resuscitation of republican tradition and festivals had a part to play in this, too. Augustan government was heavily tinged with concern for moral revival; the virtues of ancient Rome seemed to some to live again. Ovid, a poet of pleasure and love, was packed off to exile in the Black Sea when a sexual scandal at the edge of the imperial family provided an excuse. When to this official austerity is added the peace which marked most of the reign and the great visible monuments of the Roman architects and engineers, the reputation of the Augustan age is hardly surprising. After his death in

AD

14 Augustus was deified as Julius Caesar had been.

Augustus intended to be succeeded by a member of his own family. Although he respected republican forms (and they were to endure with remarkable tenacity) Rome was now really a monarchy. This was demonstrated by the succession of five members of the same family. Augustus’s only child was a daughter; his immediate successor was his adopted stepson, Tiberius, one of his daughter’s three husbands. The last of his descendants to reign was Nero, who died in

AD

68.