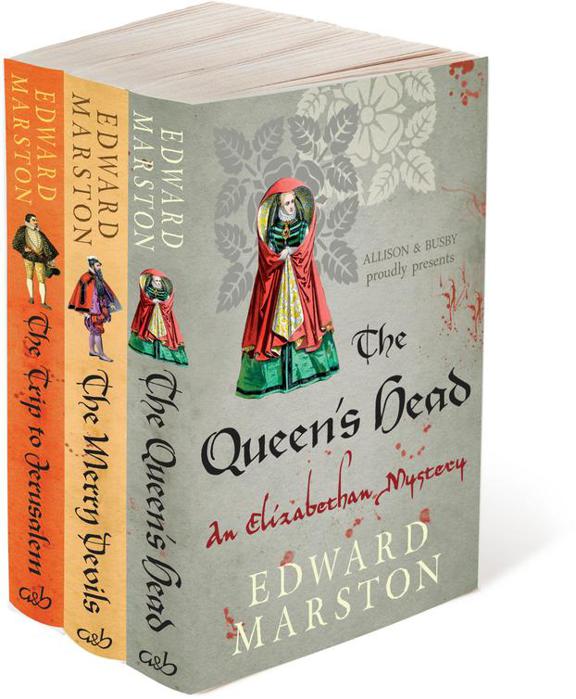

The Nicholas Bracewell Collection

- The Queen’s Head

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Prologue

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- The Merry Devils

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- The Trip to Jerusalem

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- ALSO BY EDWARD MARSTON THE NICHOLAS BRACEWELL SERIES

- About the Author

- By Edward Marston

- Copyright

TO THE ONLIE BEGETTER OF

THESE INSVING CHRONICLES

Mr. C.M. ALL HAPPINESSE

WISHETH

THE WELL-WISHING

ADVENTVRER IN

SETTING

FORTH

‘Her head should have been cut off years ago.’

Queen Elizabeth I

February 1587

D

eath stalked her patiently throughout the whole of her imprisonment. Hardly a day passed when she did not hear or imagine its stealthy tread behind her, yet it stayed its hand for almost twenty years. When it finally struck, it did so with indecent haste.

‘Tomorrow morning at eight o’clock.’

The Earl of Shrewsbury set the date and time of her execution in a faltering voice. He was part of the deputation which called on her after dinner in her mean apartments at the grim fortress. Mary was forced to get out of bed, dress and receive the men in her chamber. She was the Dowager Queen of France, the exiled Queen of Scotland and the heir to the English throne but she had to suffer the humiliations that were now borne in upon her.

Shrewsbury pronounced the sentence, then Beale, the clerk of the Council, read aloud the warrant from which the yellow wax Great Seal of England dangled so mesmerically. Everything was being done in strict accordance with the Act of Association.

Death had enlisted the aid of legal process.

Her captors gave her no crumbs of comfort to sustain her through her last hours. When she asked that her own chaplain be given access to her, in order to make ready her soul, the request was summarily denied. When she called for her papers and account books, she met with resistance again. The deputation was proof against all her entreaties.

Their licence extended beyond the grave. It was Mary’s wish that her body might be interred in France either at St Denis or Rheims but they refused to countenance the idea. Queen Elizabeth had expressly ruled against it. Alive or dead, the prisoner was to have no freedom of movement.

All further appeals were turned down. The interview came to an end, the deputation withdrew and Mary was left to soothe her distraught servants and to contemplate the stark horror of her situation.

Tomorrow morning at eight o’clock!

In an impossibly brief span of time, she had to tie off all the loose ends of a life which, for some forty-four years now, had been shot through with moments of high passion and deeply scored by recurring tragedies. Twelve days would not have been long enough for her to prepare herself and she was given less than twelve hours. It was a cruelly abrupt departure.

Supper was quickly served so that Mary could begin the task of putting her affairs in order. She went through the contents of her wardrobe in detail and divided them up between friends, relations and members of her depleted household. When she had drawn up an elaborate testament, she asked for Requiem Masses to be held in France and made copious financial arrangements for the benefit of her servants. Even under such stress, she found time to make charitable bequests for the poor children and friars of Rheims.

Her spiritual welfare now took precedence and she composed a farewell letter to the chaplain, de Préau, asking him to spend the night in prayer for her. The faith which had sustained her for so long would now be put to the ultimate test.

It was two o’clock in the morning before her work was done. Her last missive, to her brother-in-law, King Henry of France, was thus dated Wednesday 8

th

February, 1587, the day of her execution.

Mary lay down on the bed without undressing while her ladies-in-waiting, already wearing their black garments of mourning, gathered around her in a sombre mood. One of them read from a Catholic bible. The queen listened to the story of the good thief as it moved to its climax on the cross then she made one wry observation.

‘In truth, he was a great sinner,’ she said, ‘but not so great as I have been.’

She closed her eyes but there was no hope of sleep. The heavy boots of soldiers marched up and down outside her

room to let her know that she was being guarded with the utmost care, and the sound of hammering came from the hall where the scaffold was being erected by busy carpenters. Time dragged slowly by to heighten the suspense and prolong her torment.

At six o’clock, well before light, she rose from her bed and went into the little oratory to pray alone. Kneeling in front of the crucifix for what seemed like an eternity, she tried to fit her mind for what lay ahead and to ignore the sharp pains that teased and tested her joints. The sheriff of Northampton eventually summoned her and the agony of the wait was over. The longest night of her life would now be followed by its shortest day.

Six of her servants were allowed to attend her. Mindful of her command that they should conduct themselves well, they drew strength from her evident composure and fortitude. Whatever the mistakes of her life, she was determined to end it with dignity.

Almost three hundred spectators had assembled in the great hall and they strained to catch a first glimpse of her as she came in, looking on with a mixture of hostility and awe. They knew that they were in the presence of a legend – Mary Queen of Scots, an erratic, imperious, impulsive woman who had lost two crowns and three husbands, was Catholic heir to a Protestant country and could, by her very existence, inspire rebellion while still under lock and key.

Her youthful charm might have vanished, her beauty might have faded, her face and body might have fleshed

out, her shoulders might have rounded and her rheumatism might oblige her to lean on the arm of an officer as she walked along, but she was still a tall, gracious figure with the unmistakable aura of majesty about her and it had its due effect on her audience.

She was dressed in black satin, embroidered with black velvet and set with black acorn buttons of jet trimmed with pearl. Through the slashed sleeves of her dress could be seen inner sleeves of purple and although her shoes were black, her stockings were clocked and edged with silver. Her white, stiffened and peaked head-dress was edged with lace, and a long, white, lace-edged veil flowed down her back with bridal extravagance.

Mary held a crucifix and a prayer book in her hand, and two rosaries hung down from her waist. Round her neck was a pomander chain and an

Agnus Dei

. Her manner was calm and untroubled, and she wore an expression of serene resignation.

In the middle of the hall was the stage which had been built during the night. Some twelve feet square and two feet high, it was hung with black. As Mary was led up the three steps, her eye fell on the pile of straw which housed the executioner’s instrument. Her rank entitled her to be despatched with the merciful swiftness of a sharp sword but she saw only the common headsman’s axe. It was a crushing blow to her pride.

She listened with studied calm as the nervous Beale read out the commission for her execution. Mary was imperturbable. It was only when the Dean of Peterborough

stepped forward to harangue her according to the rites of the Protestant religion that she betrayed the first sign of emotion.

‘Mr Dean,’ she said firmly, ‘I am settled in the ancient Catholic Roman religion, and mind to spend my blood in defence of it.’

Resisting all exhortations to renounce her faith, she hurled defiance at her judges by holding her crucifix aloft and praying aloud in Latin and then in English. When she had attested her devotion to Catholicism, she was ready to submit to her fate.

The executioners and the two ladies-in-waiting helped her to undress. Above a red petticoat, she was wearing a red satin bodice that was trimmed with lace. Its neckline was cut appropriately low at the back. When she put on a pair of red sleeves, she was clothed all over in the colour of blood.

Her eyes were now bound with a white cloth embroidered in gold. The cloth was brought up over her head so that it covered her hair like a turban. Only her neck was left bare. She recited a psalm in Latin then felt for the block and laid her head gently upon it. The executioner’s assistant put a hand on the body to steady it for the blow.

There was a rustle of straw as the axe was lifted up by strong hands, then it arched down murderously through the air. Missing her neck, it cut deep into the head, drenching the white cloth with blood and drawing involuntary groans from an audience that was watching with ghoulish fascination. The axe rose again to make a second glittering

sweep, slicing through the neck this time but failing to sever the head from the body. With crude deliberation, the executioner hacked through the last few royal sinews.

The ceremony was not yet complete. Stooping down to grasp his trophy and exhibit it, the masked figure stood up and cried in a loud voice: ‘Long live the Queen!’ Gasps of horror mingled with shouts of disbelief. All that he was holding was an auburn wig.

The head parted from its elaborate covering, fell to the platform and rolled near the edge. From beneath her red skirts, a frightened lapdog came scurrying out to paddle in the blood that surrounded its mistress. Its pitiful whimpering was the only sound to be heard in the great hall.

Everyone was struck dumb. As they gazed at the small, shiny skull with its close-cropped grey hair, they saw something which made them shudder. The lips were still moving.

T

he Queen’s head swung gently to and fro in the light breeze. It was an interesting sight. Wearing a coronet and pearls in red hair that was a mass of tight curls, she had a pale, distinguished face with a high forehead, fine nose and full lips. Her regal beauty had an ageless quality that was enhanced by a remarkable pair of eyes. Dark, shrewd and watchful, they managed to combine authority with femininity and – when the sun hit them at a certain angle – they even hinted at roguishness. Nobody who met her imperious gaze could fail to recognise her as Elizabeth Tudor, Queen of England.

Bright colours had been used on the inn sign. Enough of the neck and shoulders was included to show that she was dressed in the Spanish fashion, with a round, stiff-laced

collar above a dark bodice fitted with satin sleeves which were richly decorated with ribbons, pearls and gems. A veritable waterfall of pearls flowed from her neck and threatened to cascade down from the timber on which they were painted. The same opulence shone with vivid effect on the reverse side of the sign. Royalty was at its most resplendent.

London was the biggest, busiest and most boisterous city in Europe, a thriving community which had grown up in the serpentine twists of the River Thames and which was already thrusting out beyond its boundary walls. Poverty and wealth, stench and sweetness, anarchy and order, misery and magnificence were all elements in the city’s daily life. From her high eminence in Gracechurch Street, the queen’s head saw and heard everything that was going on in her beloved capital.

‘Ned, that gown will need a stitch or two.’

‘Yes, master.’

‘You can sweep the stage now, Thomas.’

‘The broom is ready in my hand, Master Bracewell.’

‘George, fetch the rushes.’

‘Where are they?’

‘Where you will find them, lad. About it straight.’

‘Yes, master.’

‘Peter!’

‘It was not our fault, Nicholas.’

‘We must speak about that funeral march.’

‘Our cue was given too early.’

‘That did not matter. It was the wrong music.’

Nicholas Bracewell stood in the courtyard of The Queen’s Head and took charge of the proceedings. Noon had just brought the morning’s rehearsal to a close. The afternoon performance now loomed large and it threw the whole company into the usual state of panic. While everyone else was bickering, complaining, memorising elusive lines, working on last minute repairs or dashing needlessly about, Nicholas was concentrating on the multifarious jobs that had to be done before the play could be offered to its audience. He was an island of calm in a sea of hysteria.

‘I must protest most strongly!’

‘It was only a rehearsal, Master Bartholomew.’

‘But, Nicholas, my play was mangled!’

‘I’m sure it will be far better in performance.’

‘They ruined my poetry and cut my finest scene.’

‘That is not quite true, Master Bartholomew.’

‘It’s an outrage!’

The book holder was an important member of any company but, in the case of Lord Westfield’s Men, he had become absolutely crucial to the enterprise. Nicholas Bracewell was so able and resourceful at the job that it expanded all the time to include new responsibilities. Not only did he prompt and stage manage every performance from the one complete copy that existed of a play, he also supervised rehearsals, helped to train the apprentices, dealt with the musicians, cajoled the stagekeepers, advised on the making of costumes or properties, and negotiated for a play’s licence with the Master of the Revels.

His easy politeness and diplomatic skills had earned him

another role – that of pacifying irate authors. They did not get any more irate than Master Roger Bartholomew.

‘Did you hear me, Nicholas?’

‘Yes, I did.’

‘An outrage!’

‘You did sell your play to the company.’

‘That does not give Lord Westfield’s Men the right to debase my work!’ shrieked the other, quivering with indignation. ‘In the last act,

your

voice was heard most often. I did not write those speeches to be spoken by a mere prompter!’

Nicholas forgave him the insult and replied with an understanding smile. Words uttered in the heat of the moment were normal fare in the world of theatre and he paid no heed to them. Putting a hand on the author’s shoulder, he adopted a soothing tone.

‘It’s an excellent play, Master Bartholomew.’

‘How are the spectators to

know

that?’

‘It will all be very different this afternoon.’

‘Ha!’

‘Be patient.’

‘I have been Patience itself,’ retorted the aggrieved poet, ‘but I’ll be silent no longer. My error lay in believing that Lawrence Firethorn was a good actor.’

‘He’s a great actor,’ said Nicholas loyally. ‘He holds over fifty parts in his head.’

‘The pity of it is that King Richard is not one of them!’

‘Master Bartholomew—’

‘I will speak with him presently.’

‘That’s not possible.’

‘Take me to him, Nicholas.’

‘Out of the question.’

‘I wish to resolve this matter with him.’

‘Later.’

‘I

demand

it!’

But the howled demand went unsatisfied. Conscious of the disturbance that the author was creating, Nicholas decided to get him away from the courtyard. Before he knew what was happening, Roger Bartholomew was ushered firmly into a private room, lowered into a seat and served with a pint of sack. Nicholas, meanwhile, poured words of praise and consolation into his ear, slowly subduing him and deflecting him from his intended course of action.

Lawrence Firethorn was the manager, chief sharer and leading actor with Lord Westfield’s Men. His book holder was not shielding him from an encounter with a disappointed author. Rather was he protecting the latter from an experience that would scar his soul and bring his career in the theatre to a premature conclusion. Roger Bartholomew might be seething with righteous anger but he was no match for the tempest that was Lawrence Firethorn. At all costs, he had to be spared that. Nicholas had seen much stronger characters destroyed by a man who could explode like a powder keg at the slightest criticism of his art. It was distressing to watch.

Allowances had to be made for the fact that Master Roger Bartholomew was a novice, lately come from Oxford, where his tutors held a high opinion of him and

where his poetry had won many plaudits. He was clever, if arrogant, and sufficiently well-versed in the drama to be able to craft a play of some competence.

The Tragical History of Richard the Lionheart

had promise and even some technical merit. What it lacked in finesse, it made up for in simple integrity. It was over-written in some parts and under-written in others but it was somehow held together by its patriotic impulse.

London was hungry for new plays and the companies were always in search of them. Lawrence Firethorn had accepted the apprentice work because it offered him a superb central role that he could tailor to suit his unique talents. It might be a play that smouldered without ever bursting into flame but it could still entertain an audience for a couple of hours and it would not disgrace the growing reputation of Lord Westfield’s Men.

‘I expected so much more,’ confided the author as the drink turned his fury into wistfulness. ‘I had hopes, Nicholas.’

‘They’ll not be dashed.’

‘I felt so betrayed as I sat there this morning.’

‘Rehearsals often deceive.’

‘Where is my play?’

It was a cry from the heart and Nicholas was touched. Like others before him, Roger Bartholomew was learning the awful truth that an author did not occupy the exalted position that he imagined. Lord Westfield’s Men, in fact, consigned him to a fairly humble station. The young Oxford scholar had been paid five pounds for his play and

he had seen King Richard make his first entrance in a cloak that cost ten times that amount. It was galling.

Nicholas softened the blow with kind words as best he could, but there was something that could not be concealed from the wilting author. Lawrence Firethorn never regarded a play as an expression of poetic genius. He viewed it merely as a scaffold on which he could shout and strut and dazzle his public. It was his conviction that an audience came solely to see him act and not to watch an author write.

‘What am I to do, Nicholas?’ pleaded Bartholomew.

‘Bear with us.’

‘I’ll be mocked by everyone.’

‘Have faith.’

After giving what reassurance he could, the book holder left him staring into the remains of his sack and wishing that he had never left the University. They had taken him seriously there. The groves of academe had nurtured a tender plant which could not survive in the scorching heat of the playhouse.

Nicholas, meanwhile, hurried back to the yard where the preparations continued apace. The stage was a rectangle of trestles that jutted out into the middle of the yard from one wall. Green rushes, mixed with aromatic herbs, had been strewn over the stage to do battle with the stink of horse dung from the nearby stables. When the audience pressed around the acting area, there would be the competing smells of bad breath, beer, tobacco, garlic, mould, tallow and stale sweat to keep at bay. Nicholas

observed that servingmen were perfuming large ewers in the shadows so that spectators would have somewhere to relieve themselves during the performance.

As soon as he appeared, everyone converged on him for advice or instruction – Thomas Skillen, the stagekeeper, Hugh Wegges, the tireman, Will Fowler, one of the players, John Tallis, an apprentice, Matthew Lipton, the scrivener, and the distraught Peter Digby, leader of the musicians, who was still mortified that he had sent Richard the Lionheart to his grave with the wrong funeral march. Questions, complaints and requests bombarded the book holder but he coped with them all.

A tall, broad-shouldered man with long fair hair and a full beard, Nicholas Bracewell remained even-tempered as the stress began to tell on his colleagues. He asserted himself without having to raise his voice and his soft West Country accent was a balm to their ears. Ruffled feathers were smoothed, difficulties soon resolved. Then a familiar sound boomed out.

‘Nick, dear heart! Come to me.’

Lawrence Firethorn had made a typically dramatic entrance before moving to his accustomed position at the centre of the stage. After almost three years with the company, Nicholas could still be taken aback by him. Firethorn had tremendous presence. A sturdy, barrel-chested man of medium height, he somehow grew in stature when he trod the boards. The face had a flashy handsomeness that was framed by wavy black hair set off by an exquisitely pointed beard. There was a true nobility

in his bearing which belied the fact that he was the son of a village blacksmith.

‘Where have you been, Nick?’ he enquired.

‘Talking with Master Bartholomew.’

‘That scurvy knave!’

‘It

is

his play,’ reminded Nicholas.

‘He’s an unmannerly rogue!’ insisted the actor. ‘I could run him through as soon as look at him.’

‘Why?’

‘Why?

Why

, sir? Because that dog had the gall to scowl at me throughout the entire rehearsal. I’ll not put up with it, Nick. I’ll not permit scowls and frowns and black looks at

my

performance. Keep him away from me.’

‘He sends his apologies,’ said Nicholas tactfully.

‘Hang him!’

Firethorn’s rage was diverted by a sudden peal of bells from a neighbouring church. Since there were well over a hundred churches in the capital, there always seemed to be bells tolling somewhere and it was a constant menace to open air performance. The high galleries of the inn yard could muffle the pandemonium outside in Gracechurch Street but it could not keep out the chimes from an adjacent belfry. Firethorn thrust his sword arm up towards heaven.

‘Give me a blade strong enough,’ he declared, ‘and I’ll hack through every bell-rope in London!’

Struck by the absurdity of his own posture, he burst into laughter and Nicholas grinned. Working for Lawrence Firethorn could be an ordeal at times but there was an amiable warmth about him that excused many of his faults.

During their association, Nicholas had developed a cautious affection for him. The actor turned to practicalities and cocked an eye upwards.

‘Well, Nick?’

‘We might be lucky and we might not.’

‘Be more exact,’ pressed Firethorn. ‘You’re our seaman. You know how to read the sky. What does it tell you?’

Nicholas looked up at the rectangle of blue and grey above the thatched roof of the galleries. A bright May morning had given way to an uncertain afternoon. The wind had freshened and clouds were scudding across the sky. Fine weather was a vital factor in the performance as Firethorn knew to his cost.

‘I have played in torrents of rain,’ he announced, ‘and I would willingly fight the Battle of Acre in a snowstorm this afternoon. I care not about myself, but about our patrons. And about our costumes.’

Nicholas nodded. The inn yard was not paved. Heavy rain would mire the ground and cause all kinds of problems. He was as anxious to give good news as Firethorn was to receive it. After studying the sky for a couple of minutes, he made his prediction.

‘It will stay dry until we are finished.’

‘By all, that’s wonderful!’ exclaimed the actor, slapping his thigh. ‘I knew I chose the right man as book holder!’

The Tragical History of Richard the Lionheart

was a moderate success. Playbills advertising the performance had been put up everywhere by the stagekeepers and they

brought a large and excitable audience flocking to The Queen’s Head. Gatherers on duty at the main gates charged a penny for admission. Many people jostled for standing room around the stage itself but the bulk of the audience paid a further penny or twopence to gain access to the galleries, which ran around the yard at three levels and turned it into a natural amphitheatre. The galleries offered greater comfort, a better view and protection against the elements. Private rooms at the rear were available for rest, recreation or impromptu assignations.