The Night Fairy (4 page)

Authors: Laura Amy Schlitz

A

A

s Flory tore though the tall grass, her thoughts flew ahead of her. She knew she must work quickly. She had to fetch her dagger, warm the eggs, and free the hummingbird before the spider came back. When she reached the cherry tree, she flung back her head and bellowed, “Skuggle!”

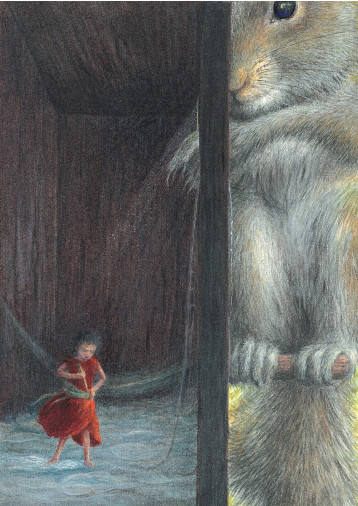

The cherry leaves shook. Skuggle peered down at her.

“Have you anything to eat?” asked the squirrel.

“No,” answered Flory. “Skug, would you do me a favor? I need to get to my house — quickly.”

“Will you give me something to eat?”

Flory rolled her eyes. “No —” she began. Then she changed her mind. “Yes. If you carry me up to my house, I’ll give you some dried cherries and sunflower seeds.”

The squirrel was at her side before she finished the word

cherries.

“Cherries,” he chattered. “I love cherries. You’re mean, Flory, to keep them all to yourself. I love them, I want them. Give them to me.”

In two seconds they were at the door of Flory’s house. “Don’t go away,” Flory commanded, sliding off the squirrel’s tail. “Wait here.”

She scrambled into her dim little house. She found her dagger and slipped it into the sash around her waist. Then she picked up the grass quilt she had woven. She rolled it tightly and lashed it to her back.

Skuggle’s paws were in the doorway, groping wildly. Flory went to her little store of food and hauled out four dried cherries and five sunflower seeds. One by one, she passed them to the squirrel.

“That’s enough,” she said, after the fifth seed.

“Don’t you have any more?” asked Skuggle.

“Yes, but you can’t have them now.”

Skuggle’s paws went on opening and shutting.

“I said, that’s enough,” Flory said. “Later.”

“But now is when I’m hungry.”

Flory was tempted to sting him. “If you take me where I want to go, I’ll give you more seeds tomorrow. I’ll give you all of them,” she said rashly.

“And all the cherries?”

Flory looked over her little stock of food. She had had to lug the sunflower seeds up the tree two by two. The cherries had been even heavier, and it was hard work to pit them. She sighed. “All right. But tomorrow, not today.”

“Tomorrow morning?”

“First thing,” Flory promised. “Now, get your dirty little mitts out of my house. I’m coming out.”

She climbed through the doorway. Skuggle was just outside the house. He nibbled the grass quilt. “Dry,” he said sadly, and took another little nip.

“One more bite and I’m going to sting you,” warned Flory. “Let me onto your back.”

He turned his tail to her. She climbed on and let him flip her to the space behind his ear.

“Where to?”

Flory hesitated. She wanted Skuggle’s help, but she didn’t want him to get close to the hummingbird’s eggs. “The fishpond,” she said, after thinking it over. “Hurry!”

The squirrel leaped to the ground. With dizzying speed he arrived at the edge of the fishpond. Flory gazed into the glassy water. She saw the goldfish gliding below.

“I hear they’re good to eat,” remarked Skuggle, “but I’ve never been able to catch any. Raccoon catches them.”

Flory felt a pang of fear as she thought of Raccoon. She recalled the thing that no animal and no fairy should ever forget: the world is full of predators. She glanced up at the sky. The blue was dimmer, and the air was growing cool. Soon the bats would come out to hunt. “You can go now,” she told Skuggle, but he squatted down next to her, his eyes fixed on the goldfish.

“We might be able to catch ’em if we worked as a team,” he said hopefully. “We’re a good team, aren’t we, Flory? Remember how you used your knife to get the suet out of the grease box? And how I ate it? That was teamwork, wasn’t it?”

Flory wanted to scream. She didn’t want to sting Skuggle — she didn’t even want to hurt his feelings — but she wanted him to go away. She could see the barberry bush from where she stood. It was going to be a hard climb, and every minute the eggs were getting colder. She dared not begin until Skuggle left. He could whisk up the fence post and gobble the eggs before she climbed to the first branch. She closed her eyes, trying to think of something that would distract him.

The door of the brick house opened. The giantess came out with a jar of seeds. “Look, Skuggle!” Flory cried. “The giantess is going to fill up the seed tube! Hurry up, so you can be the first one there!”

Skuggle bounded to his feet and scampered to the top of the fence. Flory blessed the giantess as she lumbered down the porch steps. Once the seed tube was full, Skuggle would be busy. Then a frightful thought crept into her mind: what if the giantess stopped by the fishpond?

Heavy footsteps shook the ground. Flory crouched down, making herself smaller. The shadow of the giantess passed over her. But the giantess didn’t see her. She sauntered past the fishpond, up the stairs, and into the great house.

Once the door closed, Flory breathed a sigh of relief. “Now for the barberry bush,” she said, and sprang to her feet.

The climb took all her skill. The barberry bush was leathery and tough, with purple leaves and cruel thorns. One of the thorns raked Flory’s forearm, leaving a long, painful scratch. Flory stopped to lick the blood away. Then she looked up.

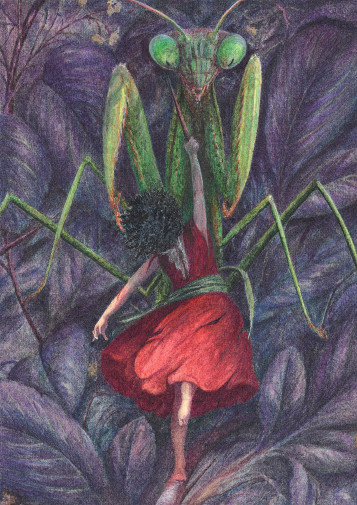

Her heart stood still. A praying mantis squatted in the barberry bush. He was less than four inches from the nest. As Flory gaped at him, his antennae twitched. He turned his head as if he knew she was there. His head was triangular, with bulging green eyes on the sides.

Flory went cold. She knew how dangerous he was — how suddenly he could strike. She also knew what was in store if he caught her. His spiky forelegs would dig into her flesh. The mantis would lift her to his bristled mouth and bite through her neck. Then he would eat her body, saving her head for last.

She opened her mouth to say her stinging spell. Then she shut it. If she stung him, he would dart away from her — closer to the nest. She wondered whether he was climbing toward the eggs or away from them. She wished she could work her seeing spell and find out if the nest was empty or full, but she dared not close her eyes.

“Night fairy,” hissed the mantis, “where are your wings?”

The word

wings

gave Flory an idea. She backed up against a thorny branch. “My wings!” Her voice was high and panicky. “Help me! I’ve ripped my wings on the thorns! I can’t fly!”

It worked. The mantis turned his long body toward her. He was eager for easy prey. Flory wanted to flee; he was a dreadful thing, and her skin crawled as he came closer. But with every step he took, he was farther from the nest.

“Night fairy!” His voice was as soft as a lullaby. “Night fairy, will you be my prey?”

His huge green eyes seemed to be casting a spell over her. He swayed back and forth. In spite of herself, Flory began to sway with him.

All at once, he struck. His spiked legs sliced the air. Flory sprang to one side and shrieked her stinging spell. Never before had she stung so hard. The mantis’s body jerked.

“Go!” shouted Flory. “Go, or I’ll sting again!”

The mantis’s eyes were full of hatred. He lurched back as if to attack. Flory drew her dagger. Instead of leaping backward, she threw herself forward, under his forelegs. She slashed upward, missing his throat by a hair. The double attack — dagger and sting — was too much for the insect. He spread his wings and flew away.

Flory watched until he was out of sight. In spite of her victory, her heart was sick. She was afraid she had come too late — that the eggs had been eaten or grown too cold. Nevertheless, she sheathed her dagger and began the last part of the climb.

The nest above her was the size of a walnut shell. The hummingbird had woven it from dry cobwebs and covered the outside with lichen, so that it blended in with the old wooden fence. Flory caught hold of the edge with her hands, hooked one ankle over the rim, and slid down inside.

The eggs were still there. Two of them, as white as pearls. When Flory touched them, she knew at once that they were too cold. They ought to have been warmer. But the creatures inside were alive. She could feel them, curled tight inside the shells: one male, one female. As she spread her fingers over the shells, she felt a glow of triumph and something else, something strong and sweet and steady. She had saved the unborn birds from the praying mantis. Now she would save them from the cold.

She pressed her palms flat against the shells and began to sing. She sang a spell of comfort for small living things. As she sang, she thought of the warmest things she knew: strong sunlight on black stone, heat lightning on summer nights, the candles that the giantess burned on the patio table. The heat of her thoughts surged through her hands. She could feel the unhatched birds yearning for it.

By the time she finished singing, the two little eggs hummed with life. Flory pushed them together and tucked the grass quilt over them. “Now,” she said, “you must stay warm until your mother comes home.” She stooped down and kissed the quilt twice. “I’m going to bring her home soon,” she added, “but you’ll be warm through the night.”

She felt to make sure her dagger was still at her side. Then she wrapped both hands around the nearest barberry twig, kicked off from the nest, and swung herself down through the branches.

It was later than she thought. Night would come soon.

N

N

ever had the garden seemed so large. Flory’s legs were scratched and aching, and the rough brick of the patio scraped the soles of her feet. Nevertheless, she set a good pace, sprinting and leaping over the cracks between the bricks.

It was growing dark. A pale star winked in the sky, and the colors of the garden were fading. The white roses glowed in the dimness like the star overhead. By the time Flory reached the juniper bush, she had a stitch in her side, but her footsteps never slowed. She must cut the web and free the hummingbird before the bats came out to hunt.

She had forgotten about the spider. While Flory had been warming the eggs, the spider had returned and found the hummingbird trapped in its web. Now the spider was wrapping its prey, creeping around and around the open wings, wet silk dripping from its spinnerets.

Flory stood stock-still, gazing upward. The spider was a large creature — a female, no doubt, as male spiders are puny. Her black-and-yellow body was as long as Flory was tall, and a good deal fatter. She was beautiful, in a scary, black-and-yellow sort of way, but she was deadly. Flory thought of the spider’s fangs digging into her and shivered. Nevertheless, she spat on her hands and caught hold of the bottom strand of the spiderweb.

The spider’s head jerked up. Although she had eight eyes, her eyesight was poor. She couldn’t see Flory, but she felt the web move under the fairy’s weight. The spider swung downward, hanging from a thread. She grumbled something that sounded like “feast or famine” and “always the way.” The hairy forelegs twitched, testing the air. “Why, it’s a fairy!” cried the spider. “What’s a fairy doing in my web? Are you stuck?”

She did not sound unfriendly. It took Flory a moment to gather her thoughts. “I’m not stuck,” she answered. She took care to speak more politely than usual; she had an idea that spiders must be treated with respect. “I came to free the hummingbird. Don’t you think she’s a bit big for you to eat?”

“I can eat her,” said the spider. “I’ve never caught anything I couldn’t eat. For that matter, I could eat you.” She gave a low chuckle. “Mind you, I don’t want to. They say it’s bad luck to kill a fairy, and I don’t fancy bad luck. But I could eat you, missy — if I wanted to.”

Flory didn’t doubt it. Seeing the spider up close, she was tempted to leap down from the web and shriek for Skuggle. She cast a nervous glance at the hummingbird. The bird hung limp, eyes closed. “You’ve poisoned her!” Flory said accusingly.

“Not yet,” answered the spider. “I like to wrap ’em before I bite ’em. That way you don’t waste so much juice.”

Flory’s thoughts raced. If the hummingbird hadn’t been bitten yet, there was still hope. “If you haven’t bitten her, why isn’t she moving?”

“She’s gone into torpor,” the spider explained. “Hummingbirds do that. When they run out of strength, they slow their bodies down. That’s why she looks dead — but she’s not. A good thing, too. I don’t like dead meat. I like it hot and juicy.” She nodded toward a grayish bundle on the other side of the web. “Take that wasp. He’s still alive and kicking. What I say is, a dead wasp is nasty, but —”

Flory forgot about being polite. “Why not eat the wasp?” she interrupted. “You don’t need a whole big bird to eat. Why don’t you eat the wasp and let the hummingbird go?”

The spider looked affronted. “Who do you think you are?” she asked. “Telling me what to eat! I’ll eat what I choose, missy! It’s no business of yours.”

“It is my business,” Flory said rashly. “The hummingbird’s my friend. If you try to bite her, I’ll sting you. And I’ll stick you with my dagger.” She drew her knife and brandished it fiercely. “Let her go!”

The spider’s eyes gleamed faintly red. All at once, she swung downward, heading for Flory. The black-and-yellow legs swung into action, moving with incredible speed.

Flory panicked. She shouted her stinging spell so fast that she mixed up the magic words. The spider danced closer. Flory closed her eyes. She thought of the spell she used when making cobweb ropes. She imagined a vine spiraling toward the sun, twisting, twisting. The words spilled from her lips.

When she opened her eyes, she saw that the spell had worked. The threads of the cobweb had coiled tightly, snagging the spider in her own web. Ropes of silk fettered the black-and-yellow body. Sticky threads gummed the spider’s mouth shut. Three of the eight legs were folded under themselves. The other five stuck out at queer angles, twitching helplessly.

Flory gave a little gasp. She wasn’t sorry that her spell had worked, but it was clear that the spider was in great pain. It was also clear that Flory had made an enemy. The spider’s eyes bulged with rage.

“I didn’t mean it.” Flory said hastily. “I mean, I meant it, but —” Her voice trailed off as she eyed the spider’s left foreleg. It was so bent and crooked that it made Flory feel a little sick. “Here — hold still. That leg’s going to snap in two if I don’t — Hold still, I say! I’m going to cut the ties.”

She clenched the knife and darted forward, nicking the thread that held the spider’s leg. The leg shuddered back into place.

“There!” Flory said nervously. “Is that better?”

The spider glared at her. Flory hesitated. Then she switched her knife to her other hand so that she could wipe her sweaty palm on her skirt. Her heart beat fast as she cut the threads that bound the other seven legs. When she finished, the spider was still her prisoner, but the eight legs hung straight and free, like the petals of a black daisy.

“Now!” Flory said briskly. “Don’t you feel better?”

The spider flexed her legs, making sure they still worked. Her eyes were still furious, but it was clear that she was no longer in agony.

“I have an idea,” Flory announced. “I’d like to cut the threads around your mouth so that we can talk things over. Only you mustn’t bite me. Promise me you won’t bite me.”

There was no answer. Flory took a deep breath. Then she wedged the blade of her knife under the threads around the spider’s jaw. She tried to keep her hands as far from the great fangs as she could, but she couldn’t cut the cords without getting close. The spider’s fangs were sharply pointed and curved inward, like the horns of a bull. Flory knew that the poison inside those fangs was powerful enough to turn her bones and muscles to soup. Her stomach felt queasy with terror, but her hand did not shake. She sawed carefully until she cut the thread from the spider’s jaw.

The spider opened her mouth and said a long string of bad words.

Flory couldn’t blame her. She waited until the spider had run out of things to say. Then she said, “Here’s my idea.” She pointed to the web, which was dotted with little gray bundles. “You have other good things to eat in your web. If you promise not to eat the hummingbird, I’ll set you free.”

“Why shouldn’t I eat the hummingbird?” demanded the spider. “Isn’t she my prey? Didn’t I work to weave the web that caught her? Don’t I have to eat?”

Flory’s hand dropped to her side. It was true what the spider said: every creature in the garden had to eat. That was the law. The spider had only been obeying it. But —

“You could eat wasps,” Flory said stubbornly. “Promise not to eat the bird, and I’ll set you free.”

The spider scowled. “What if I won’t?”

“Then you starve to death,” Flory said unkindly. She put her hands on her hips. “I can sting you. And I can tie you up. So you have to do what I say.”

The spider shook herself, straining against the ropes around her belly. “I’m not promising anything unless you say you’re sorry.”

It was Flory’s turn to scowl. She had never said she was sorry in her life. She didn’t like the idea of saying it. “I won’t,” she said. “Besides, I’m cutting you free. You ought to be grateful.”

“I’m not free yet,” answered the spider, “and I’m not grateful.”

Flory stamped her foot. “I’m not asking you to starve,” she said irritably. “All I’m asking is for you not to eat the hummingbird.” After a minute she added, “Or me.”

“And all I’m asking is for you to say you’re sorry,” retorted the spider. “You hurt my legs and you hurt my pride. So you have to say sorry, and”— a glint of malice lit her eyes —“you have to say it right.”

Flory laid her hand on the hilt of her dagger. “What do you mean, ‘say it right’?”

“I mean you have to mean it,” the spider said. “If you don’t say you’re sorry, I’d rather stay here and starve. I

will

starve, and it will be all your fault.”

Flory made an angry little noise in the back of her throat. This was all taking too long. The spider was her prisoner, and prisoners shouldn’t tell their jailors what to do. All the same, Flory knew she had met her match. The spider was as stubborn as she was. She shut her eyes and tried to imagine being sorry. It was hard work, almost like casting a spell.

She imagined that she was a spider, a proud and dangerous spider. She imagined what it was like to spin an elegant web, only to be caught in it herself. She imagined having eight legs and having them twisted and trapped and hurt. After a moment, she bit her lip.

“I’m sorry,” she said in a low voice.

“That’ll do,” said the spider. “Cut me free.”

Flory stuck her dagger back in her sash. “You haven’t promised not to eat the hummingbird.”

“I promise,” answered the spider. She gave a low chuckle. “Truth is, I don’t like raw bird very much — but I hate the way birds leave a big hole in my web. I ought to give her”— she jerked one leg to point at the hummingbird —“a pinch and a poison, just for making such a mess! But when all is said and done, I hate wasps more than birds. There’s things I could tell you about wasps that would make your blood run cold.”

Flory thought that her blood had run cold enough for one evening. She said, “I’ll try to free the bird without cutting your web too much.”

“Hmmmph.” The spider tapped the web with one oily foot. “That’s good of you. But if I were you, I wouldn’t cut her loose just yet. Wait until dawn.”

“Why?”

“Look at her.” The spider shook herself, freed at last. “She’s still in torpor. If you cut her loose, she’ll fall. She’s safer in the web than on the ground.”

“But I have to cut her loose. She has to go home.” Flory raised her eyes to the unmoving bird. “How do I wake her up?”

“You can’t,” said the spider. “That’s the thing about torpor. She won’t come out of it till the sun rises and she warms up.”

“But she has to fly

now,

” Flory said. “She has to go back to her nest, and I have to go home.”

“She’s not going anywhere tonight,” said the spider.

Flory’s heart sank. Night had almost fallen. The green plants looked gray, and the stars were brightening. At any moment, the bats would leave their hollow in the oak tree. It was time to take shelter in her safe little home — but if she left, the hummingbird would be food for any animal that found her.

Flory said slowly, “I can’t stay here and guard her —”

“Nobody asked you to,” said the spider. “What I say is, every creature has to take care of herself.”

Flory agreed. She had taken care of herself ever since she was three days old. She thought of her lily-leaf hammock and how tired and scratched and sore she felt. Then she remembered the baby hummingbirds. She had kissed them and promised them that their mother would come back.

“Oh, all right!” she said furiously. “I’ll stay.”

“Suit yourself,” said the spider. “I’m going to eat that wasp. Do you want a piece?”

“No, I don’t,” Flory said firmly. “I don’t like wasps — not even to eat.”

The spider began to pick her way up the web. She turned back. “If you’re going to spend the night in the web, you should know that the cross-threads are the sticky ones.”

“Thank you,” said Flory. She meant it.

The spider shinnied away. Flory was left alone. She climbed up the juniper bush and settled down close to the hummingbird. A dog barked in the distance. Flory had an odd sense that something was missing. Then she knew what it was. The birds had stopped singing. They were roosting for the night instead of leaping from branch to branch.

Suddenly the night was alive with shrill sounds. It was the moment Flory had been dreading. She gripped the juniper twig until her fingers ached. She heard leathery wings beating the air and saw the jagged shapes of bats against the sky. But they did not come looking for her. Bats hunt in the air, not close to the ground.