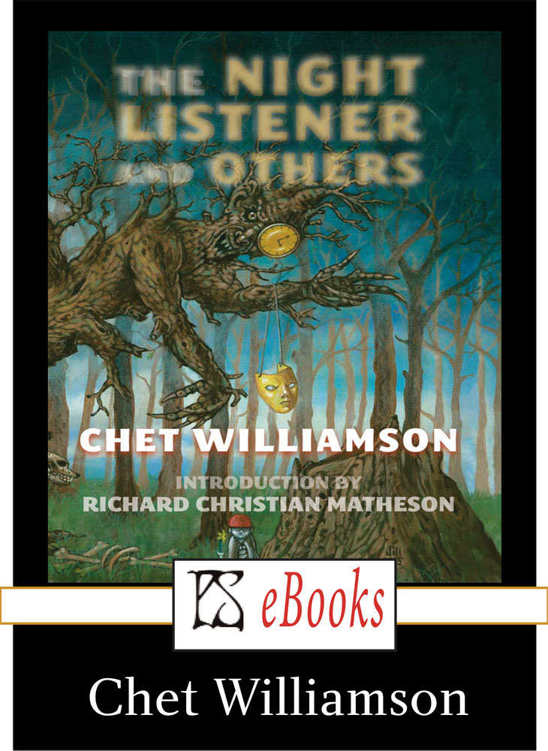

The Night Listener and Others

Read The Night Listener and Others Online

Authors: Chet Williamson

The Night Listener & Others

by

Chet Williamson

Introduction by Richard Christian Matheson

Introduction

When I began writing short stories, I took particular note of authors who blended originality and elegance. Either was rare; both a regal improbability.

Incapable of the merely probable, Chet Williamson transcends the taxidermy that passes for much of contemporary writing, stirring admiration in peers, famished demand in readers, and cloudbursts of devout ink from critics. In a field gasping with juiceless prose, his hypnotically graceful work, whether in novels or short stories, is a rescuing oxygen.

From the start, Williamson’s writing glided over black ice, eluding category. With horizon tilted and voice refined, he quickly became an understated star in the best anthologies and top magazines, including

Playboy

,

Esquire

, and

The New Yorker

, elevating the game. Horror, suspense, autopsies of modernity. It seemed he could do it all.

Consider the paranoid spell of

The Searchers

, in which three CIA operatives are tasked with debunking the venal agendas of psychic fraud and other paranormal duplicities that threaten America—a transgressive ride, wild and distressing. And Williamson shimmers.

In a departure which exports his gifts into a nightmarish, Japanese fairy tale, his novella,

The Story Of Noichi The Blind

, captures supernatural horrors with unsettling brushwork. He has even turned its traumas into a play for puppet theater, and like the Noh actors of Japan, leaving behind the world of pretense, evolving into places beyond earthly constraint, Williamson’s work mourns and overwhelms, doing exactly that. As an interesting side note, he has confessed to a fondness for all things Japanese; perhaps a past life. Given this novella, perhaps an embroiled one.

Among his nearly twenty books and over 100 short stories, are the anti-hunting suspense novel,

Hunters

, and the fierce indictment of religious zealotry and sexual abuse in his novel,

Defenders Of The Faith

, each more of Williamson, unable to stop himself from being riveting. As with all his work, duality is a provocateur, explored with harrowing insight.

Somehow bringing to mind the nervous ecstasy of Miles Davis, Williamson’s superb story collection,

Figures In Rain

, gathers dark, brilliant magic, the tales of love and loss chronologically arranged in order of their first appearances in print. The book includes his observations about each story and won the International Horror Guild Award…another in the spire of nominations and honors heaped on Williamson’s work.

He has written adaptations, rich with haunting nuance, like

The Crow: Clash By Night

and

The Crow: City Of Angels

, not to mention “The Blood-Red Sea,” a pacifistic Crow tale, poignantly suggestive of the poet Homer. His best-selling book to date is

Pennsylvania Dutch Night Before Christmas

, a Yule tale that became a regional sleeper. In a twist befitting his varied passions, he also wrote about the history of a college in

Uniting Work And Spirit: A Centennial History Of Elizabethtown College

. Stand back for its effect; Williamson could make a grocery list involving.

He dangerously strolls wounded streets in

McKain’s Dilemma

, a detective yarn written in the unenlightened days of 1988 that pivots, rather controversially for its time, on a gay character and even AIDS as possible villains; politically incorrect now, beyond bold then.

Though his ideas are remarkable, it is his characters that most powerfully define Williamson’s depths as a writer, running on red blood and lingering complexity; his pages rich with the tormented and heroic, the cruel and somehow redeemed; his very human cast lost and sometimes found, amid heartbroken scapes.

Some argue it is Williamson’s short stories with their sterling cadences and potency that most soar. As a minimalist at heart, I love the claustrophobia, irony, and misleading simplicity of them. Among the trove, my personal favorite is “The Heart’s Desire” a subversive story of longing for former days and the torturing untruths in a life falsely recalled. I find it a perfect story, written with lyricism, empathy, and not a drop of sentimentality.

Though often about pain-seeped lives, and fluent in the twisted and forbidden, Williamson judges none by judging all; a daring trick. Few are untouched, all are changed, and he is a fearless witness. There is no knowing where Williamson will next smuggle his prodigious knack. Whatever genre he chooses, crossing borders of length and style, he will simply fit in like a local and quietly make trouble. Without a creative country, the man is a danger. For those privileged few, lucky enough to be new to the miraculous Chet Williamson, you are about to enter worlds of glorious and sinister wonder.

I envy you.

Richard Christian Matheson

Malibu, California

To Laurie, who lives with me in every word…

The Night Listener

I begin to be aware of the sounds of night when my wife buys the electric blanket. Oh, there have been other sounds before—the hushed roar of the furnace, the weary hum of late-night cars passing on the road at the bottom of the yard, the whir of the refrigerator—but the electric blanket is what opens my ears to the night and makes me

hear

, makes me aware of what is waiting in the dark, what is stirring just outside, unheard by those who welcome sleep, shrouding themselves under covers, closing themselves off to the warnings.

It is that premeditated, deliberate

click

of the thermostat, as if a black finger had come down on a metal button, that keeps me on my back, eyes opened wide, fixed on the single red eye of my individual control on the headboard. The light for my wife’s side hovers over her sleeping head, bathing her hair in a crimson glow, and I think these two lights are like the piggish eyes of a monster whose head is as big as the bed, who could swallow us up, covers, mattress, box spring and all, before moving to the next house.

A fancy, that, and one at which I am quickly able to smile. But that steady clicking continues. Every few minutes I hear it, and it brings me back from the half-sleep I have entered. I remember then the books I have read as a boy, in which Tarzan awakes from sleep to a sharp alertness, with none of the slow drifting up that civilized man experiences, no dull druglike flicking of eyelids, jarring from the light, none of that. It was once necessary to survival to awaken quickly, like an animal. It may be necessary still.

I practice with the blanket.

Click.

I awake, alert, eyes wide, pupils huge, struggling to make light from darkness. There is nothing. I allow myself to sleep again.

Click

. Again I awake, muscles tensed, ready to spring up, to move right or left. My wife sleeps through it all.

That is how I spend the night—awake, asleep, awake, asleep, over and over again, like a Pavlovian dog trained for insomnia. The next morning it is strange, but I feel rested, even vital. I consider having my wife return the blanket, but decide not to. There is something deeper here, something beyond switched-on switched-off night. There is a reason for me to spend the night on sleep’s fine edge. Soon I learn what it is.

It is outside. I hear it several nights later, rustling the bushes by the bedroom windows. At first I think it is the wind, and I listen for the rapping of the yew limb on the roof overhang, but it never comes. So I listen more intently, not fading into sleep after the blanket’s most recent

click

as I usually do, and I hear it moving around the outside of the house, passing and pausing at the front door, sliding around toward the backyard, stopping at the back door, and then moving on. And somehow I know that it will not enter tonight, nor perhaps ever. It will pass by, and I will wait for its return. I will be alert, and will wake from my surface sleep to meet its coming.

I go to the next room where my young son lies sleeping, his door ajar. Through the crack I listen for his light, shallow breath. There is silence. I strain to the uttermost, but still cannot hear him, so I push the door open slowly, lifting up on it to keep the bottom from rubbing on the carpet and making a noise to wake him. He has thrown the covers back in his nocturnal tossings. Leaning over him, I listen on

pointe

for the sweet small breaths whistling in and out. I hear them now and touch the warmth of his cheek, allowing my index finger to slip beneath his tiny nose, where I feel the light puffs of lung-heated air. A kiss on the cheek, and I straighten up, tucking the quilts and blankets under his shoulders so that his own weight holds them on securely. Then I look about the room in the weak yellow glow of the night-light.

The curtains are drawn, the windows closed against the bitter cold. The furnace is running, and the hot air makes the curtains above the heat duct billow outward, as if someone is standing behind them three feet above the floor. Finally the furnace stops, the shape becomes a curtain once more, and the house falls silent. I listen, but there is nothing, and I leave the room and go back to bed, where my wife sleeps soundly. And well she may, for I am awake to listen.

More weeks pass, and I hear it once nearly every night now. I stay awake until the sound of its shambling through the winter-dry grass assails my ears, and then, naked, I rise silently from the bed and follow it as it moves around the outside of the house, the two of us like the plastic Scottie dogs whose feet are magnets, so where one moves on one side of a thin plane, the other moves as well.

Past the drawn curtains of the living room we go, through the dining room out to the kitchen, pausing at the double-locked back door. If I pull the sheer curtains back I may see it just outside, its face pressed against the cold brittleness of the storm-door pane.

Then I hear it move away. A loose stone rattles on concrete as it crosses the drive, a bone-dry leaf cracks in the grass at its passing, and the weeds in the field snap like kindling. The night is silent again. I visit my son’s room to cover him, and return to my bed. My skin is mottled with goose-prickles, and I slide toward my wife to steal her warmth. She shivers in some secret dream as my coldness attacks her, but only for a moment, and then she burrows closer, the unselfish sacrifice that love demands ruling her even in sleep. In a minute I am warm, and I think of how much I love her and the boy. With that thought embracing me, I allow myself to sleep just a breath from waking. It has never come back twice in one night, but that does not mean it never will. As long as I remember this they will both be safe.

Two weeks later it leaves and returns in the same night, and I know that the confrontation is drawing near. It comes again some time after I return to my bed—how long I cannot say, since the night devours time. There is a rubbing noise that makes ripples in the pond of sleep, and my head, just below the surface, breaks water and I wake. I know it has returned, for I hear its sound of passage, a sound I know as well as my dear wife’s gentle breathing. And there is another thing now.

There is a smell to it, light yet unmistakeable. I do not know when I first noticed it, and I suppose it came upon me little by little as one grows aware of a dull ache. It smells like flowers. Not the pleasing scent of fresh-cut blooms, but of flowers just past their prime, just when the edges of the petals start to curl and discolor, and the thought that soon they must be discarded diminishes the looker’s joy. It is the scent of shadowy death crossing life’s border.

I smell it now: not the lingering wisps of odor left by its first visit, but the full aroma of its presence. It is directly outside the window next to our bed, and it makes a thin scrabbling sound as if tapping at the sash with spindly nails. I throw off the covers, put my feet on the chilly floor, and rise as furtively as a wraith, so that the bed-frame makes no creak to disturb my wife’s slumber.