The Nine Lives of Charlotte Taylor

For Sigrid Anna Stephenson Taylor

Intrepid, incorrigible, intelligent—like Charlotte

PREFACE

The Bay

2004L

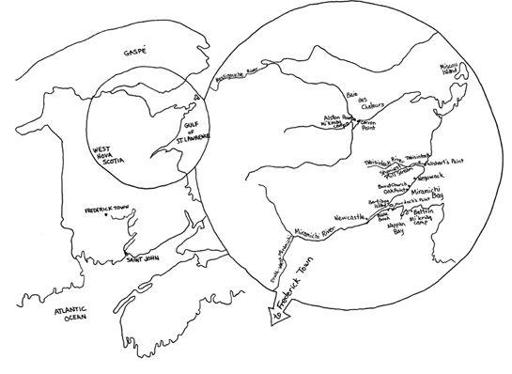

ike an unfinished symphony, her story played on my mind for most of my life. It would rock to the tune of the passage of time, an adagio of high notes, low notes and illusive movements. Then when I least expected it, I happened upon the missing notes in the life of Charlotte Howe Taylor.The rising sun is stretching out over Alston Point as I cycle along the boardwalk on the Baie de Chaleur in northern New Brunswick. A glint catches my eye and I glance sideways, trying to keep the bike upright on the narrow path. The morning rays are bouncing off a newly installed bronze plaque. Curious, I leave the bike and wade through knee-high shimmering sea-grass to find out what warrants a marker at the end of Youghall Beach.

The inscription sends shivers up my spine. Line by line it spills out details I’ve been searching for. Recently erected government plaques do not usually resolve historical mysteries. But

seeing this one, I realize that while I was toiling away in the archives and searching for birth and death dates in family Bibles trying to piece the Charlotte Taylor story together, an archaeologist had discovered a connection I’d overlooked.More than two hundred years ago, this point of land, not much more than the end of a sand dune really, had been the site of the only trading post in the vast northeast. The proprietor, Commodore George Walker, ran a brisk trading business between England, the West Indies and this place, Nepisiguit. One of the men he worked with was Captain John Blake, who would become Charlotte Taylor’s first husband.

Charlotte was a woman who upset many preconceptions. Her descendants say she fled her home in England with the family’s black butler, bound for the West Indies. Historians claim she was the first woman settler on the Miramichi River. How she got from what was supposed to be sanctuary in Jamaica to John Blake’s tilt on the Miramichi was a mystery. George Walker seems the likely shepherd, the man who not only brought her to these shores, but also the one who arranged her marriage to Blake, ten months after she arrived. This spot, memorialized in bronze, is where Charlotte Taylor began her life in Canada in 1775. I’m certain of it.

She is far from me in time and circumstance but connected to me by the ties that bind. Her often remarkable, sometimes questionable and certainly redoubtable story is told every time my family gathers.

Charlotte Taylor lived most of her life just one hundred kilometres south of this beach. Every summer during my youth, we would travel from the family cottage at Youghall to visit my mother’s extended clan at Wishart’s Point and Tabusintac near

the Miramichi. And at every gathering, the aunts and uncles, my parents and grandparents would sit around the kitchen table of the old farmhouse—the very house Charlotte herself had built in 1798—telling tales of the woman who first baked bread at this hearth.She was a woman with a past. Not exactly a gentlewoman. It was said that she came from an aristocratic family in England, although there wasn’t much that seemed genteel about the settler my elders always referred to as “that old Charlotte.” Words like

lover

and

land grabber

drifted down from the table to where we kids sat on the floor, but the family also had a powerful respect for her, as if their own fortitude and guile were family traits passed down from the ancestral matriarch. For as long as I can remember, I’ve tried to imagine the real life she lived and how she ever survived it.The family house we return to today is where she raised her many children and plotted her next step in the survival stakes of settling in the New World. Land grants could make or break a family’s fortunes. Immense forests thick with spruce were both enemies and friends to settlers who desperately needed to clear the land and plant a crop so they’d have enough food to survive the winters, and to trade the tall timbers in the region’s burgeoning lumber business. The Tabusintac River, which loops around three sides of Wishart’s Point, was the waterway Charlotte depended on for news and for material goods. It was also her route back to the rough-hewn world that was the Miramichi River, where she had first settled in 1776. The relentless coastal winds that blow from the northeast and the northwest, whipping up storms from the sea as well as brutal winter blizzards, are as much a part of life around the old homestead today as they were when Charlotte struggled with the elements.

The geese that flock to the fields in spring, and gather again for their autumn flight, still stop to feed on her land.As a child, one of the rituals of my summertime visits was a trip to the Riverside Cemetery for a prayer service. The time-worn grave markers of Charlotte Taylor and her offspring are mixed in with the new marble tombstones in this peaceful place perched on a cliff overlooking the Tabusintac River. Her marker, a moss-covered, pock-marked stone that measured a foot by six inches and lay flat in the green grass, was simply labelled “Charlotte Taylor, 1755–1841.” The magnitude of the memory versus the size of the marker troubled me as a child. What had she done to warrant such minimalist treatment at the grave and such nonpareil biography at the dinner table?

From the riverbank beside the burial ground, you can see her homestead at Wishart’s Point in the distance and gaze over the uncluttered wilderness she would have confronted every day. Standing here, you can imagine her struggles and triumphs, from the time she staggered to the shore until a canoe, paddled by the Mi’kmaq, carried her to this resting place.

On dark winter nights back home in Montreal, my siblings and I would beg for more stories of the “olden days” and ask our mother endless questions about Charlotte Taylor, our great-great-great-grandmother.

“She came to this country with nothing but a trunk full of clothes that suited a lady more than a pioneer,” she’d tell us. Her own father (my grandfather) was born just forty-five years after Charlotte died. “He told us the stories about burying food in a pit by the river so they’d have something to eat in the winter. We stored food in the same pit when I was a girl,” my mother said. But like my grandfather, she used to raise her eyebrows and make remarks about the unbecoming behaviour of a woman

who had three husbands. My Uncle Burt used to wink at the gathered family and say, “Sly old Charlotte had her way with men and with their land as well.” What

had

happened to her husbands? I once asked whether she had killed them. My question was met with hoots of laughter that only served to heighten my fascination.She was a woman whom historian William Ganong called “a remarkable early settler.” Her obituary in the

Royal Gazette of Newcastle

described her as “a respected woman who was the third British settler” in the region. But hers is not a story of a woman in starched white petticoats and a beribboned bonnet, displaced from the Old World and trying to re-create it in the new one. She managed to keep her ten children alive through the American Revolution that was fought on her doorstep, the Indian raids that burned out her neighbours and the droughts and floods and endless winters that challenged her wit and tenacity. She was of this place.I have spent ten years on and off searching for hooks to this elusive woman and became hooked myself—on shipping schedules from 1775, on Mi’kmaq history, on settler survival skills and the clash of Acadian, Loyalist and pre-Loyalist personalities.

In 1980, during the Old Home Week celebrations that are held every five years in Tabusintac, the memorial service at the cemetery featured the unveiling of a prepossessing new headstone for Charlotte that heralded her as “The Mother of Tabusintac,” a fitting epitaph since almost every family from here can trace its roots to her. The stone stands first in the cemetery as you enter by the main gate. It is made out of granite, tough enough to withstand the storm of time—just like the woman herself. And it also has an error, rendering her death

date as 1840 when, in fact, she died in 1841. There’s nothing inscribed that speaks of the compassion and grace in her rugged life, or hints at the rogue in her.After Old Home Week in 1995, when I got back to my desk as editor-in-chief of

Homemaker’s Magazine

in Toronto, I decided to write my editorial letter about her, wanting to share the story of one of the earliest settlers in Eastern Canada with my readers. As a result, the magazine received letters from her descendants from all over the world. They came from England and Saudi Arabia, from the United States and Kenya, and expressed the same passion and pride I’d known since childhood. I wrote to each of these far-flung branches of Charlotte’s family tree and asked for their memories and memorabilia. In return I learned of her winter trek by snowshoe from the Miramichi to Fredericton, more than two hundred miles away, and of her bitter quarrels with the Loyalists who came to the river after the American Revolution. Almost all of my correspondents mentioned a liaison with a Mi’kmaq man.The archives in New Brunswick provided facts about births, marriages and deaths, and also handwritten, sometimes desperate petitions for land titles. Historians such as Ganong, and before him the explorer and erstwhile entrepreneur Nicolas Denys, faithfully recorded the details of those early days in what would become northern New Brunswick.

It wasn’t yet a province when Charlotte set foot there. Canada was still ninety-two years short of its official birthday. All of the territory east of Quebec was called Nova Scotia except for the tiny Isle Saint-John, which was renamed Prince Edward Island in 1799. The Mi’kmaq (called Micmac by the settlers) were considered mentors by the Acadians, wily traders by men like Commodore Walker and savage enemies

by the British military. When Charlotte arrived, the Acadians who hadn’t taken refuge from the expulsion in Mi’kmaq camps were staggering back to the land after twenty years in exile. Tabusintac, the Miramichi and Nepisiguit (present-day Bathurst, New Brunswick) were part of a vast wilderness that claimed the lives of many soldiers, settlers and traders.Charlotte Taylor lived in the front row of history, walking the same path as the Mi’kmaq, the Acadians, the privateers of the British-American War and the Loyalists. Her story is shaped by the howling nor’easters, the isolating winters, the grind of daily survival and the devastating circumstances that stalked her growing family.

Her adventurous spirit is what’s on my mind as I stare at the marker on Youghall Beach on a July morning before the rest of the world is awake. At this wondrous time of day, you can leave your footprints like first tracks on the sandbars. You can watch, at a silent distance, a great blue heron pausing to feed on the shoreline. Sun dapples the water of the Baie de Chaleur, creating dazzling mirrors of light. It strikes me that Charlotte could have seen this too.

Did she walk these sandbars before paddling south to the Miramichi? Was she a runaway frightened by her new surroundings or thrilled by her sudden bolt from home? I know only one other thing about her life before she landed here, a secret that she carried with her from England.