The Northern Crusades (3 page)

Read The Northern Crusades Online

Authors: Eric Christiansen

Tags: #History, #bought-and-paid-for, #Religion

MAP 5

The Lithuanian Front, 1280–1435

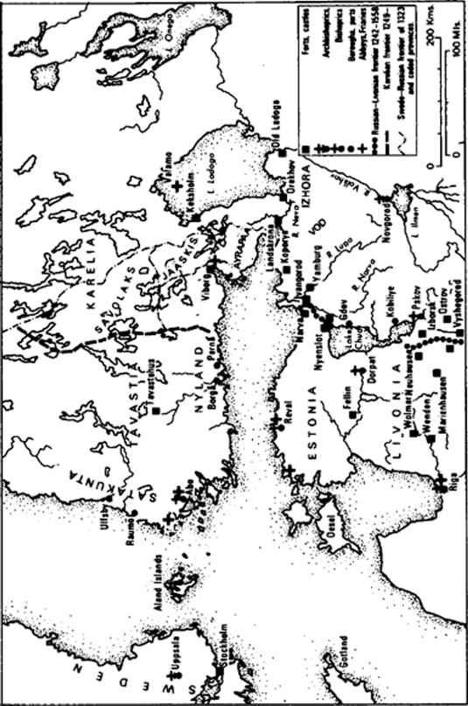

MAP 6

The Russian Front, 1242–1500

The crusades to the Holy Land are well known, or, at least, widely heard of. The crusades against the Albigensian heretics, and against the Muslims of Spain, are familiar to students of medieval history. But the crusades of North-East Europe remain outside the scope of most English readers, and are remembered, if at all, as the subject of Eisenstein’s haunting essay in nationalist propaganda, the film

Alexander Nevsky

. He is said to have chosen the subject because so little was known about it that the facts were unlikely to interfere with his fictions.

This book is an attempt to describe the struggles waged round the Baltic from the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries in the name of Christianity, and to explain the part they played in the transformation of Northern societies which took place at the same time. There is no room for more. The general history of the Baltic world will only be referred to in so far as it directly concerns the crusades, and the reader will have to look elsewhere for a proper account of the rise and fall of the Scandinavian kingdoms, the East European principalities, the Hanseatic League, the fish trade, the German colonization of the East, the development of cities, churches and shipping.

The starting point comes at the end of the Viking Age, when Scandinavian rulers found themselves shut off from the long-range overseas conquests of the past, and challenged by newly invigorated Slav nations in home waters. After a survey of the Northern world as it was in 1100, the story moves round that world, concentrating in turn on those areas and periods most involved with the crusades: beginning with the south-west Baltic in 1147, when the pope first authorized a Holy War against the heathen of the North, and ending with the Russian frontier at about 1505, when the very last Northern crusading Bull was sent from Rome. In the intervening period the lands the crusaders conquered had been changed almost out of recognition – in population, speech, culture, economy, government. It would not be altogether accurate to say that they had been civilized, or Catholicized, but these phrases express one part of what had happened: the part that involved the coming of the main components of medieval culture from their cradles in France, Italy and the Rhineland, and the development of trade and resources by imported skills. Describing this process in full would require a very different sort of book, and focusing on even the limited topic of the crusading ventures has made it impossible to say much that ought to have been said. I apologize for the gaps, and hope that the reader will recognize, even in the darkest passages, that there is a plan.

Telling this story means keeping at least three balls in the air at the same time: a narrative of campaigns; a survey of ideological developments; and a sketch of political history. The crusades can be understood only in the light of, for example, the Cistercian movement, the rise of the papal monarchy, the mission of the friars, the coming of the Mongol hordes, the growth of the Lithuanian and Muscovite empires, and the aims of the Conciliar movement in the fifteenth century. Dealing briefly with all these big subjects, and linking them to the far north of Europe, has not been easy; and an English reader may well ask, is it worthwhile?

There are several reasons for answering yes. In the first place, the Northern crusades were a part of a wider Western drive, and if that is to be studied it should be studied in full – in the most unlikely places, and in the most peculiar forms. The Holy Wars of the Mediterranean brought about spectacular conquests, and enduring obsessions, but amounted in the end to a sad waste of time, money and life. After 200 years of fighting, colonization, empire-building, missionary work and economic development, the Holy Places remained lost to Christendom. The Saracens won. The two faiths remained invincibly opposed, and if the cultures mingled it was not because the Christians had attempted to conquer the Near East; there were more enduring and less explosive points of contact.

The Northern crusades were less spectacular, and much less expensive, but the changes they helped to bring about lasted for much longer, and have not altogether disappeared today. The southern coast of the Baltic is still German, as far as the Oder; and it is not sixty years since the Estonians and Balts lost the last traces of their German ascendancy and fell under a new one. Western forms of Christianity survive in all the coastlands opposite Scandinavia, and the Finns remain wedded to

Western institutions and tolerant of their Swedish-speaking minority. The reborn republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania look west for support and sympathy. For seven centuries these east-Baltic countries were colonial societies, bearing the mark left by their medieval conquerors whatever outside power tried to annex or change them. If ever the crusades had any lasting effect, it was here, and in Spain.

Secondly, the Northern crusades were a link between this region and Western Europe; they helped bring it into a common ‘Latin’ civilization. Not the only link, but a steely one, and difficult to ignore. New Catholic societies were founded in hostile and unfamiliar territory. How to run them, defend them and develop them were problems to be met with on all the frontiers of Europe, both in the Middle Ages and later, and they have an interest that is more than local. Here were the great central institutions – churches, manors, castles, boroughs, feudal law-codes, church law, guilds, and parliaments – translated into a cold, dark and inhospitable outer world, forced to adapt, grow, or go under. This was not a promised land, glittering with the allurements of Spain or Palestine; the victories, profits, and the harvest of souls had to be wrested painfully in the face of exceptional obstacles. The study of these institutions on their home ground, or in hot-house colonies, is well established and keenly pursued; but at least as much can be learned about them by looking at them under stress, beyond the pale. The story of the Northern crusades can provide one such insight, and make the picture of medieval culture a little clearer.

And, finally, the story concerns England more than many other countries. Despite the Norman conquest, and the involvement of English kings in France, England was never cut off from the Baltic world, and after 1200 became more and more firmly connected by trade, by political alliances and by the crusading movement. In the 1230s, Henry III granted a special privilege to the association of Baltic traders based on the island of Gotland, and a pension to the Teutonic Knights who had embarked on the conquest of Prussia; while at the same time an English bishop was leading the Swedes to baptize and annex the peoples of central Finland. Between 1329 and 1408 several hundred Englishmen served under the Teutonic Order in the crusade against Lithuania, and in 1399 one of them, Henry Bolingbroke, became King Henry IV of England. Quarrels and treaties between English kings, the Hanseatic League, the Teutonic Order in Prussia and the Scandinavian rulers recurred

throughout the fifteenth century, and from the 1340s onwards the clothvending English merchant was a regular interloper in Baltic commerce, lured by tar, wax, fur, corn, longbows and timber. What happened in this distant world mattered in England, and mattered all the more by reason of the Northern crusades.

For these reasons the story deserves to be retold. Few subjects have been worked at more exhaustively by continental historians, mostly Germans, during the last 150 years. Few remain more impenetrable to the English reader unfamiliar with German. For the most part, what is presented here amounts to a small scree on the mountainside of German and Scandinavian

Ostforschung

, with a few pebbles from Russia, Poland, Finland and the liberated Baltic republics thrown in. But the reader must be warned that the author has made very little reference to the attitudes and general conclusions of his sources. This may obscure the fact that the issues involved are by no means all dead ones, and that contentiousness remains a dominant characteristic in the field of medieval Baltic history.

It has long been so, because the powers that dominated the region in the nineteenth century tended to justify current policies by rewriting the past, and identify themselves either with the crusaders or with their enemies. Thanks largely to the scholarship of Johannes Voigt, and to the journalism of Treitschke, the Teutonic Knights came to be seen as the harbingers of the Prussian monarchy, the Second Reich and German

Kultur

. ‘What thrills us,’ declared Treitschke, ‘is the profound doctrine of the supreme value of the State, which the Teutonic Knights perhaps proclaimed more loudly and clearly than do any other voices speaking to us from the German past.’ ‘A spell rises from the ground which was drenched with the noblest German blood,’ he intoned; and meanwhile, the foes of German imperialism denounced the Teutonic Knights and praised the rulers of Novgorod and Poland as champions of Slav nationality. (For example, the great Polish antiquary J. Lelewel, who wrote of the Teutonic Order, ‘They created a monastic state, which was an insult both to humanity and to morality.’) When nationalist movements got under way in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, the polemical chorus grew louder; all that had happened in the distant past of these countries was either indicted as a crime against humanity or sanctified as a ‘stupendous and fruitful occurrence’. By no means all historians followed these fashions, but they were so much in accordance with the spirit of the

times that millions were affected by them. In 1914 the name ‘Tannenberg’ was applied to Hindenburg’s repulse of the Russian armies in East Prussia, in deliberate ‘revenge’ for the defeat of the Teutonic Order in 1410; and, later on, Himmler’s plan to mould the S S as a reincarnation of that Order proved yet again the irresistible strength of bad history. Many Soviet Balticists wrote under a cloud of pure nineteenth-century Panslavism, merely streaked with dialectical materialism of the same vintage. All the honest and meticulous work of modern scholars has made little impression on the versions of Baltic history commonly received.

This is understandable. The southern and east Baltic coastlands have had more than their share of misery in the twentieth century. The forces of the modern world – fascism, communism, total war, and industrialization – have smashed almost every town from Kiel round to the Arctic Circle at least once within living memory, and have crushed both their servants and their victims with an oafish destructiveness that makes the wars of the Middle Ages seem almost picturesque by comparison. At least 5¼ million inhabitants of these coasts fled or were driven into exile between 1939 and 1950; few will ever go home. The Baltic became a political backwater, but the cost of this tranquillity was an implacable grievance among the millions who have left, and a continuing series of wrongs done to the millions who stayed put. In such a climate, old wounds do not heal, and old quarrels are not forgotten, even by historians. The interpretation of conflicts between Christianity and paganism, between Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, between German, Balt and Slav, still rouses passion after the ending of the Cold War.

The work on which the first edition of this book was based was composed in haste over twenty years ago, and the author has had time to repent of the many errors and misconceptions which it contained. The flowering of Baltic and Northern medieval research since then has made it necessary not only to correct mistakes, but to revise almost every conclusion drawn from the evidence. The very notion of ‘crusade’, as it existed in the 1970s, has been largely discredited, and dark areas of Lithuanian and North Russian history are being continually lit. These developments have resulted in a fuller section on further reading at the end of the book, although work published in English or French is still scarce.

ON THE EVE OF THE CRUSADES

This is where the great North Russian Plain stops. It ends with a horseshoe of mountains and plateaux, curving round from Finland into the Scandinavian peninsula, and with an interlocking barrier of water, the Baltic Sea. It is the presence of this sea which gives the region its peculiar character; that, and the great rivers which connect it with more temperate climes.