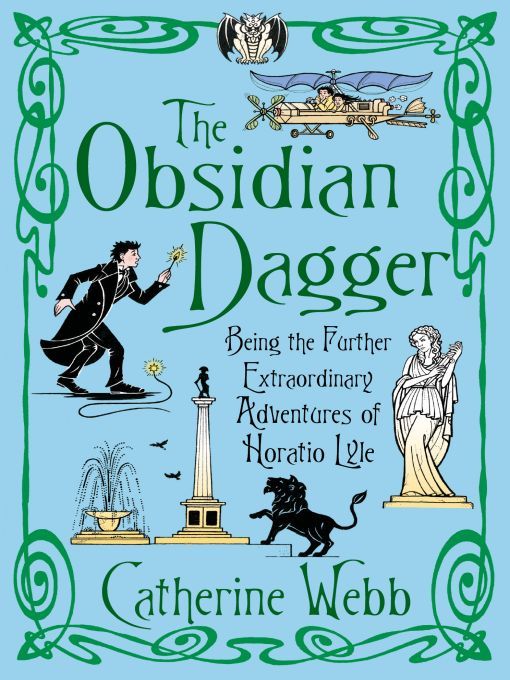

The Obsidian Dagger (Horatio Lyle)

Read The Obsidian Dagger (Horatio Lyle) Online

Authors: Catherine Webb

The Obsidian Dagger

CATHERINE WEBB

Hachette Digital

Table of Contents

Catherine Webb

was just fourteen when she wrote her extraordinary debut,

Mirror Dreams

. With several novels already in print at nineteen, Catherine has quickly established herself as one of the most talented and exciting young writers in the UK.

was just fourteen when she wrote her extraordinary debut,

Mirror Dreams

. With several novels already in print at nineteen, Catherine has quickly established herself as one of the most talented and exciting young writers in the UK.

By Catherine Webb

Mirror Dreams

Mirror Wakes

Waywalkers

Timekeepers

Mirror Wakes

Waywalkers

Timekeepers

The Extraordinary and Unusual

Adventures of Horatio Lyle

Adventures of Horatio Lyle

The Obsidian Dagger: Being the

Further Extraordinary Adventures

of Horatio Lyle

Further Extraordinary Adventures

of Horatio Lyle

The Obsidian Dagger

CATHERINE WEBB

Hachette Digital

Published by Hachette Digital 2008

Copyright © 2006 by Catherine Webb

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor

be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover

other than that in which it is published and without a

similar condition including this condition being

imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters and events in this publication, other than those

clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance

to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

eISBN : 978 0 7481 1113 8

This ebook produced by Jouve, FRANCE

Hachette Digital

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DY

An Hachette Livre UK Company

INTRODUCTION

London

London, 1864

It is said that there are forces beyond any mere man’s control. Some call it magic, some call it God, some call it luck, some call it fate. Very few know what it really is. And they’re the few who it, whatever ‘it’ may be, will never change.

It is said that, when everything else is sleeping, the stones of London Town whisper to each other. The old cobbles of Aldgate murmur to the new of Commercial Road, telling them what a world they have inherited, what a place, what a hunger, pouring out their history, whispering with the changing tide as the Thames rolls gently from here to there and back again, bringing with it little pieces of the world outside, which are quickly lost and consumed in the city.

It is said that, when every footstep is silent, the city is alive, aware, breathing, warning its brief inhabitants of danger coming from afar, and fighting it with the experience of centuries.

Except, perhaps, tonight.

Winter.

In Heron Quays the last coal-carrier looks up as he heaves the final sack of black, lumped will-be-soot up from the base of the barge, just a small shape in a city of ships clinging to the side of the river, and sees, a long way above, the first few specks of snow caught briefly in the moonlight, as they drift towards the river, which shimmers in the dark corners where sunlight never reaches, still and frozen.

In St Mary’s Church, Cheapside, the priest stops hacking at the long icicles hanging from his once-white spire, now almost black with soot, as the first snowflake touches gently on the brass bell of the tower, which seems to hum an old, forgotten tune picked up by the bells of St Paul’s and St Pancras, which whisper to each other:

Hark, hark, the dogs do bark,

The beggars are coming to town.

The beggars are coming to town.

The snow is trodden under the feet of the costermongers calling out in Brick Lane and Chapel Market and Whitecross Street and along Poultry and down Maiden Lane, until it is black and slushed and clings to the black ice that hides between the rounded cobbles for protection against the onslaught of hobnails and chipped leather and baked suede and rolling wooden wheels and iron hooves and bare toes turned blue.

It falls across the light of the single lantern burning in the darkness on the deck of a ship, old and unusually tattered, rigging hanging down as if it has just sailed through a storm, its mast one branch in a forest of ships that sit, creaking to each other about the places they have seen, the spices and silks and sailors and smells that they have carried from Aberdeen to Zanzibar. The snow settles on the deck, where even the salt water, that has seen more oceans than the moon, begins to shiver and whiten in the cold.

The snow falls outside a tall window, through which yellow light spills, eclipsed only by the black outline of a man. For a second the light warming the snow turns red as it catches a slurpful of port, swirled absently in a crystal glass, and the glass hums in sympathy to the voice that says, ‘One would have thought, that if they wished to avoid this situation, they would not have permitted him to be moved. It is unfortunate when our allies’ failures inconvenience us.’

‘Yet it may work to our advantage, my lord.’

The owner of the voice regards the black and white landscape, pinpricked with yellow lamps and dirty candlelight, blurred behind the still-falling snow that blends at knee height with a grey-green fog rising off the frozen river, and wears an expression which implies that here is a phenomenon which, if it knows what is good for itself, won’t come anywhere near

his

shoes, and says in a voice colder than the icicles on every uneven roof and tortured drain, ‘I will not underestimate this ... person.’

his

shoes, and says in a voice colder than the icicles on every uneven roof and tortured drain, ‘I will not underestimate this ... person.’

‘Is your agent not competent? Mine is.’

Yellow light turning red, port swirling in a glass, settling again. For a second the moon tries to make itself known over one of the clouds, but if the snow doesn’t eat up its light before it can touch the cobbles, then the smoke does. ‘He is competent. But . . .’

‘My lord?’ A voice, not entirely familiar with the sound of English, raised in polite enquiry.

Yellow light, turning red, port swirling in a glass, drunk, gone. A little sigh, appreciation of the finer things in life, and nothing else besides. ‘He has an unfortunate inclining that we really cannot countenance.’

‘Which is, my lord?’

‘Scruples,

xiansheng

.’

xiansheng

.’

The snow builds up against a long window in a tall house that overlooks a steep hill, inside which a voice like marble warmed in the sun whispers to itself, ‘So soon.’ The owner smiles, and thinks of a time when the snow was heavier, whiter, colder, and there weren’t nearly as many fires to drive it away.

And the snow falls on a tall, dark-haired man half-caught in the light of a ship’s dull lantern, who says, ‘You should not have brought him here, captain. He will cause no end of trouble!’

A voice, fast, scared, teeth chattering in the cold, coming out of the darkness, across the loose rigging and old, battered, salt-stained wood, ‘He’s safe! I make sure! He go nowhere!’

‘He came

here

.’ A voice like stone, like the stones around, baked London clay, white Portland stone, granite and scarred limestone, yellow sandstone and chimneys of old, blackened brick. ‘You brought him here after he had waited alone for so long, you brought him

here

and now we are all in danger.’

here

.’ A voice like stone, like the stones around, baked London clay, white Portland stone, granite and scarred limestone, yellow sandstone and chimneys of old, blackened brick. ‘You brought him here after he had waited alone for so long, you brought him

here

and now we are all in danger.’

‘I not know, I not know, the man he say . . .’

‘Which man?’

‘The man! Who come with the letter and say he was priest, and he say he go and see that cargo ready and . . .’

‘He’s here? Now?’

Horror in the voice, horror and fear, a deep-down true knowledge of what is to come. And still the snow falls on the crooked roofs of Bethnal Green, on the tight, winding alleys of St Giles, on the high peaked roofs of Mayfair, on the carriages of Belgravia, on the dome of St Paul’s and the steel slope of Paddington, on the trains of King’s Cross and on the barges of the Thames, which gobbles up each snowflake and grows fatter, whispering always the old stories that run from Bromley to Barnes, from Swiss Cottage to St James, from Highbury to Holborn, and say,

Hark, hark, the dogs do bark,

The beggars are coming to town.

Some in rags, and some in tags,

And one in a velvet gown.

The beggars are coming to town.

Some in rags, and some in tags,

And one in a velvet gown.

And the snow falls between the pillars of the Royal Institute and through the cracks of the collapsing slums of Whitechapel and Bow, on the carts of the costermongers, the laden carts from Dover, the snorting train to Edinburgh waiting for the last passenger to save his top hat from a savage vent of steam, on the top hats and frilled bonnets, on the tinker, tailor, soldier, sailor, rich man, poor man, beggar man, thief, on the lass selling roasted nuts in Drury Lane, on the man setting up his stall of dark green watercress while the bells ring out across Old London Town, each in their own little temporal universe that will never agree with its neighbour, telling stories of when the city was smaller than it is now, and the people crowded into the garrets of Holborn, and the world stopped at Hyde Park, where the murderers were taken to die, and the snow falls on an old ship, just one tree in a forest of masts, and on a dark-haired man who’s just felt horror and fear for the first time in his life, and realized that, again for the first time, he is standing with his back

against

the light.

against

the light.

Other books

A Baumgartner Christmas by Selena Kitt

Crushed by Lauren Layne

The Innocent Man by John Grisham

Fear in the Sunlight by Nicola Upson

Cruel Doubt by Joe McGinniss

Chango's Beads and Two-Tone Shoes by William Kennedy

Second Earth by Stephen A. Fender

Sublime Wreckage by Charlene Zapata

Holding Their Own: A Story of Survival by Joe Nobody

An Oath of Brothers by Morgan Rice